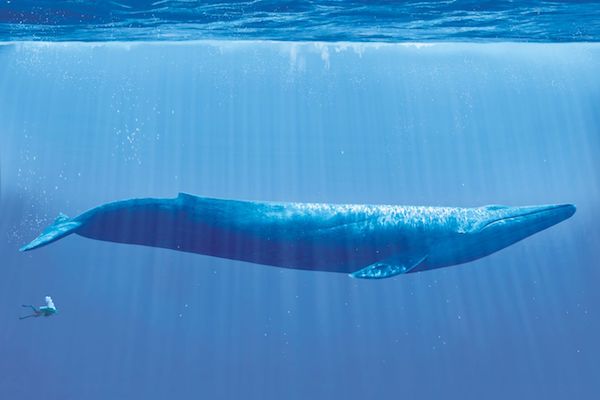

By Dr. Karmen L. Schmidt

Have you heard of the word, thairm? Neil Munro in Ayrshire Idylls (1912) writes disparagingly of “The sordid pot of tripe and thairm”. Och! Turns out, this is the Scottish word for intestine, the topic of today’s Anatomy Lesson #47, Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut.” We resume the multi-lesson tour of our fantastic GI Tracts!

The bowels , a.k.a., intestines, gut, guts, entrails, viscera, insides, or innards, are critically important for survival. Times have changed: my parents would not allow their kids to use the word gut, thinking it crass. But, anatomists, especially embryologists, use gut as a scientific term, so, let’s go!

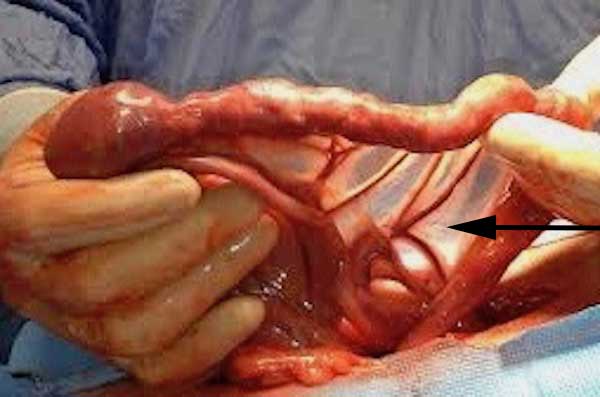

WARNING: Image I is a surgical specimen of human small intestine. If your wame is wobbly, you might eat first!

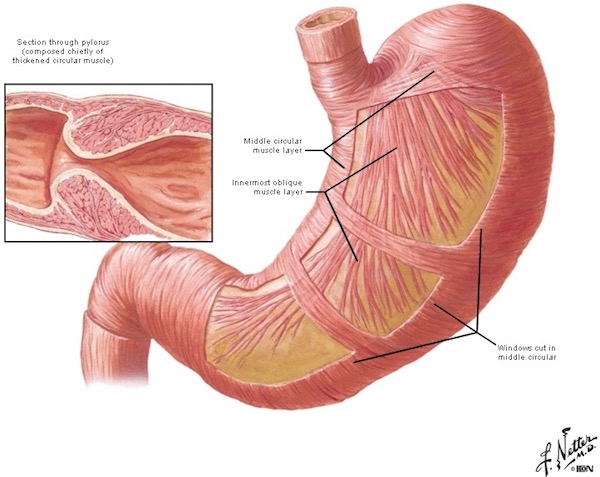

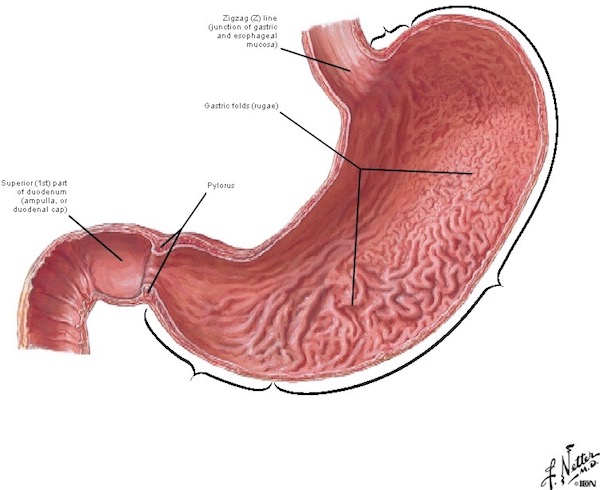

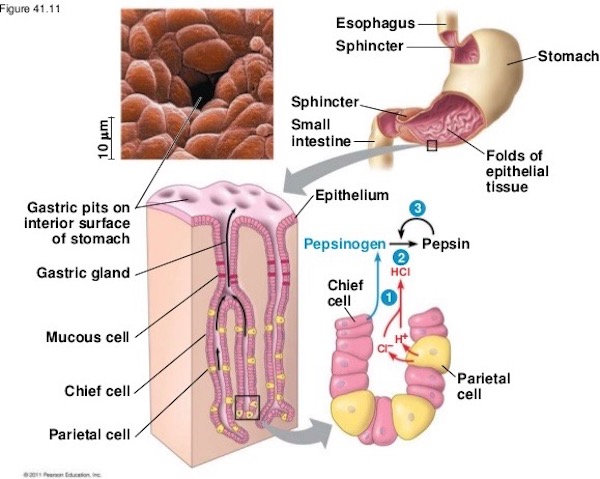

Our last lesson (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach, Wobbly Wame) informed us that “stuff” enters the stomach as individual boluses (globs) of swallowed food and drink. After mixing with gastric fluids, chyme, an acidic, watery mass is formed and released into the small intestine by controlled opening and closing of the pyloric sphincter.

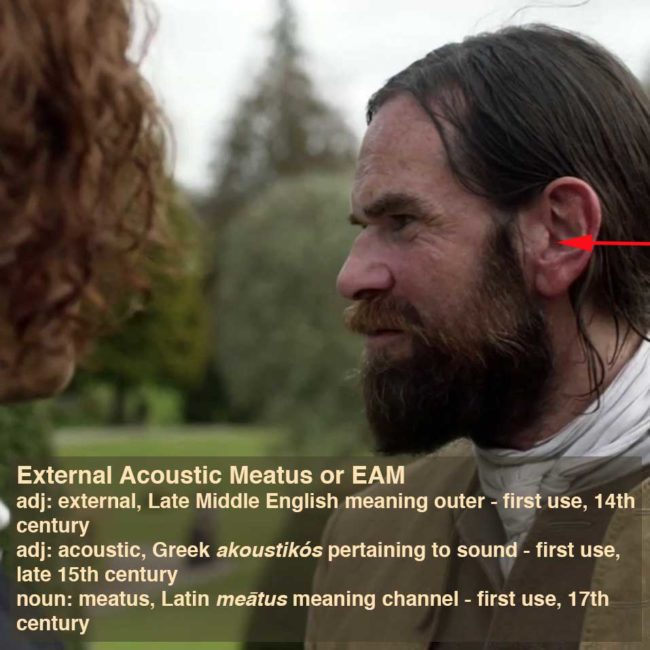

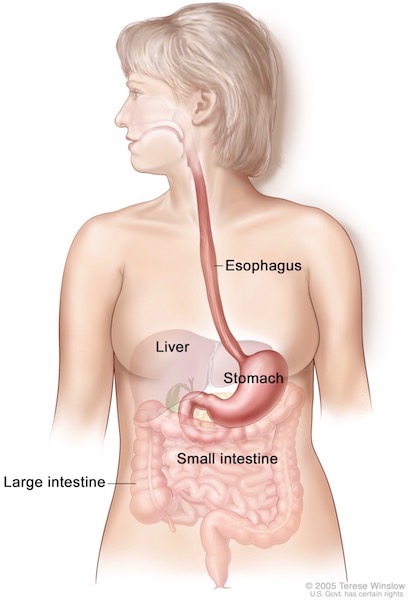

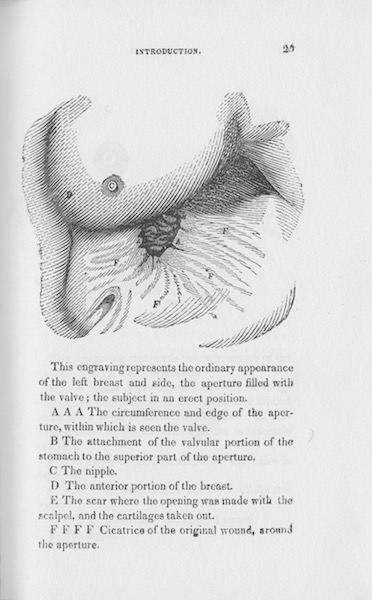

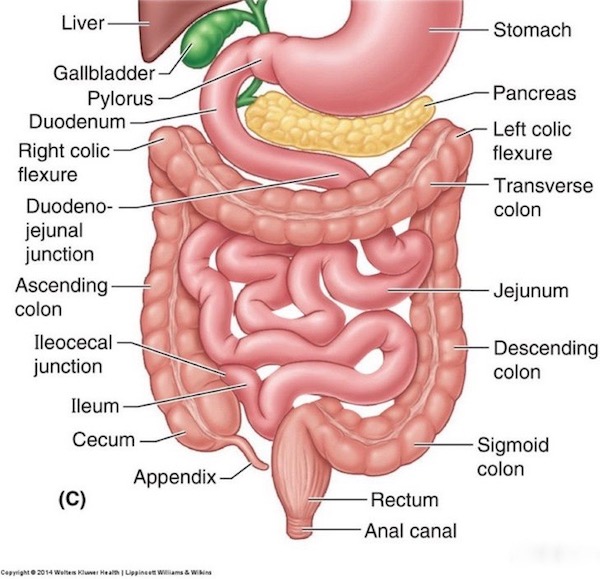

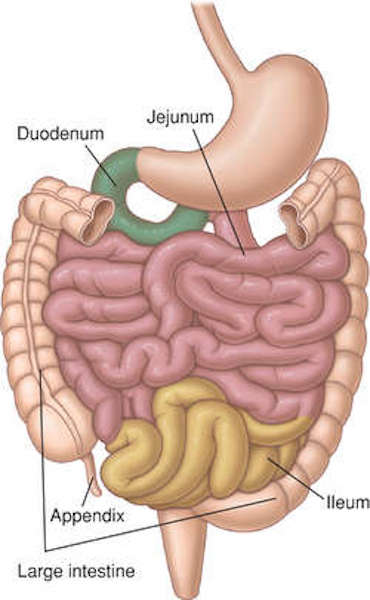

Overview: Our intestine extends from pyloric sphincter (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach – Wobbly Wame) to anus and is divided into small intestine and large intestine (Image A). An adult small intestine is about 20 ft (6 m) long; large intestine is 5 ft (1.5 m). Whoa! If small intestine is longer than the large intestine, then why is it small? Because, the large intestine is wider: 3” diameter compared with 1” for small intestine. Not my fault! <g>

Image A

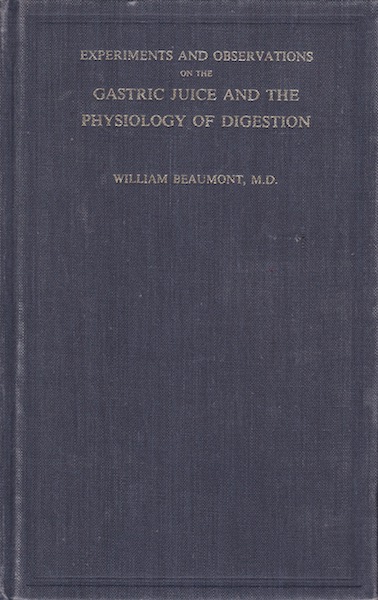

Humble Pie: Our intestines are teenie-weenies compared with those of an adult blue whale (Image B); their small intestine is about 720 ft long! Hum… let’s see, now… a US football field is 360 ft long so, a blue whale’s intestine is twice the length of a football field! And, its diet is composed entirely of wee creatures (krill. etc.). Just sayin’… let us be humble!

Image B

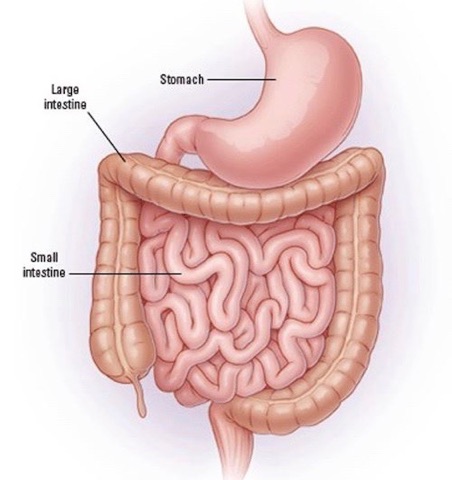

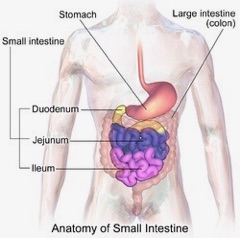

Divisions: Like other body parts, anatomists subdivide intestines based on differences in form and function. Thus, intestines fall into two major segments, small intestine and large intestine both of which have subdivisions (Image C):

small intestine

- duodenum

- jejunum

- ileum (spell check: ilium is part of hip bone! Anatomy Lesson #39, Dem Bones – Human Skeleton)

large intestine (to be covered next lesson!)

- cecum

- appendix

- colon

- rectum

- anal canal

Image C

Small Intestine: Ever see a tall man squeeze into a small car? Likewise, the small intestine must adapt its 20’ length to the confines of the abdominal cavity. It does so by folding into loops. Gordie demoed his intestinal loops in Starz episode 104, The Gathering!

Puir Geordie, a boar’s tusk lacerated his anterior abdominal wall (Anatomy Lesson #16, “Jamie’s Belly” or “Scottish Six-Pack”), exposing his innards. Like Dougal, we wept for ye, man…Diana explains Geordie’s dire circumstances in Outlander book:

What couldn’t be stopped was the ooze from the man’s belly, where the ripping tushes had laid open skin, muscles, mesentery, and gut alike. There were no large vessels severed there, but the intestine was punctured; I could see it plainly, through the jagged rent in the man’s skin. This sort of abdominal wound was frequently fatal, even with a modern operating room, sutures, and antibiotics readily to hand. The contents of the ruptured gut, spilling out into the body cavity, simply contaminated the whole area and made infection a deadly certainty. And here, with nothing but cloves of garlic and yarrow flowers to treat it with.…

Verra sad.

Psst…. Pig entrails may have been used in ep 104, as the diameter looks a bit wide for human small intestine, but convincing, none the less. Congrats, to the Outlander special effects team!

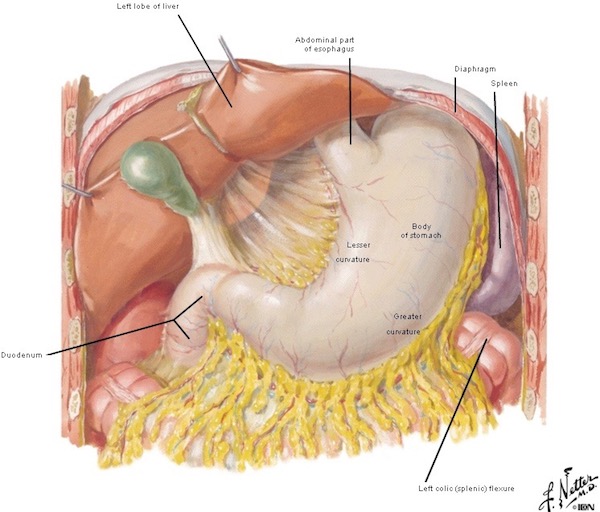

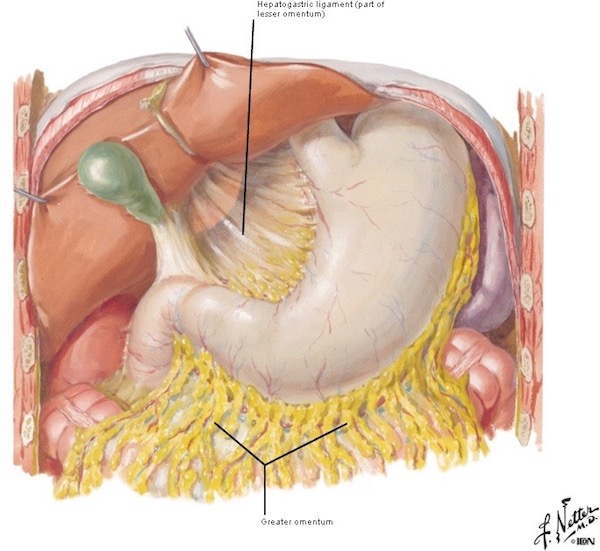

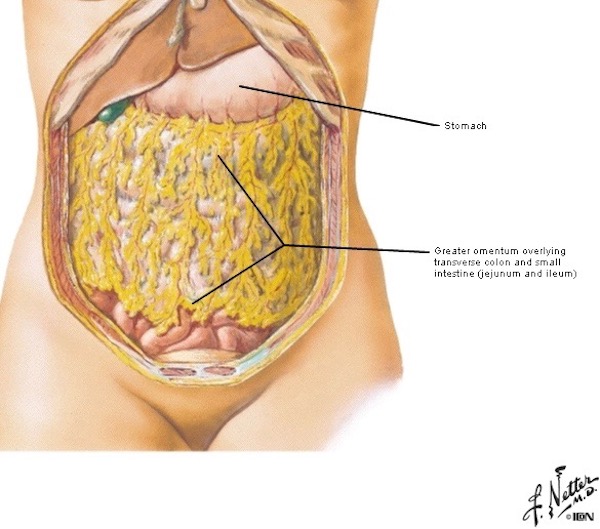

Opening the body wall, does not usually reveal much small intestine (Image D) because most of it is covered by the fat-filled greater omentum, hanging from the greater curvature of stomach (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach – Wobbly Wame).

Image D

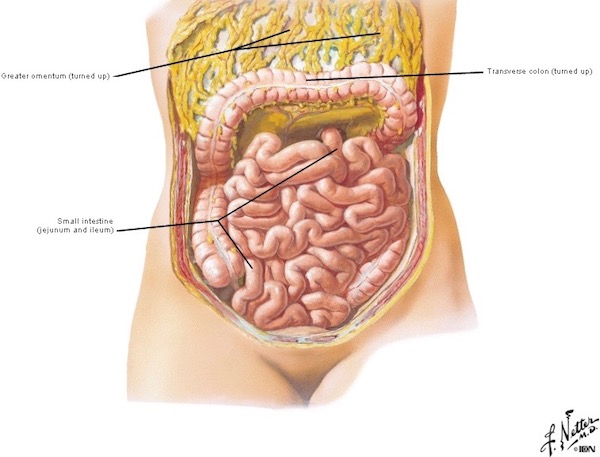

Lifting stomach, transverse colon (part of large intestine), and greater omentum toward the head reveals coils of small intestine (Image E) nestled in the abdominal cavity. When standing, some loops typically slip into the pelvic cavity. See that although jejunum and ileum are labelled in Image E, duodenum is not because it lies at a deeper level (described below).

Image E

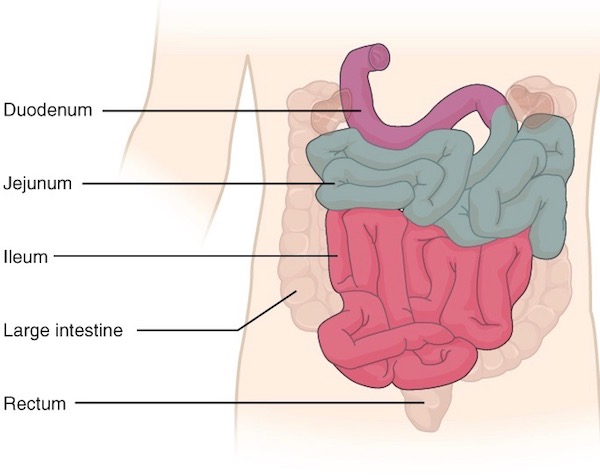

As noted above, small intestine is divided into three regions from proximal (near end) to distal (far end): duodenum, jejunum, and Ileum – let’s examine each part.

Duodenum: Only by moving large intestine and removing a mesentery (membrane) is the duodenum exposed.

Just so you ken, the word duodenum is pronounced du·o·de·num (four syllabi), not, du·ode·num (three syllabi). The word comes from the Latin duodeni meaning “in twelves.” Why? Because the length of duodenum roughly equals the breadth of 12 adult fingers ~ 1 ft, some 15% of the overall length of small intestine.

Try this: Lay hands side-by-side and imagine two more fingers added at one end. That’s the length of duodenum. Got it? Grand!

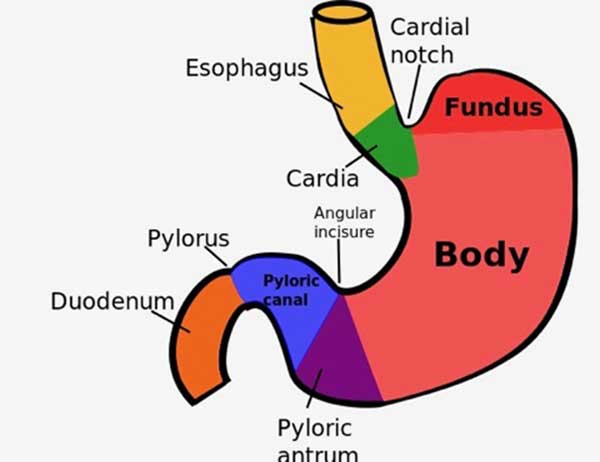

Duodenum (Image F – purple) starts at the pyloric sphincter of stomach and ends at the jejunum (Image F – green). Also, notice it assumes a C-shaped curve which has an important purpose – we will return to this feature later.

Image F

Jejunum: Jejunum comes from the Latin word jējūnus meaning empty or fasting; so named because it was often empty of food after death. The duodenum abruptly ends at a flexure created by a suspensory structure (ligament of Treitz), the spot where jejunum begins (not shown in Image G).

Jejunum makes up 8 ft (38%) of the small intestine (Image G – pinkish) and ends at start of ileum (Image G – yellow).

Image G

Ileum: Ileum (Image H – hot purple) is the longest and terminal part of small intestine, some 13 ft in length (47% of small intestine). Ileum comes from the Greek word, eilein, meaning to twist up tightly; the coiled ileum certainly gibes with its word root! It ends at the cecum, part of the large intestine.

Image H

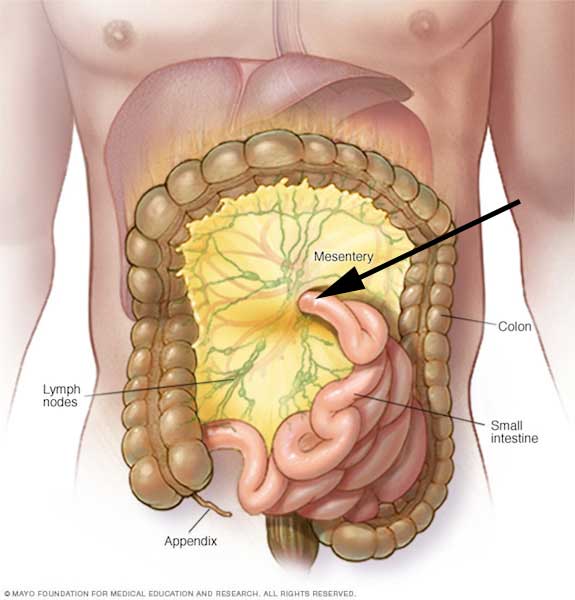

Small Intestine Mesentery: You might think that small intestine slips willy-nilly around the abdominal cavity, but that is not so. Although intestinal coils do move, they are anchored by mesentery, part of the peritoneal lining of the abdominal cavity (Anatomy Lesson #9, “The Gathering” or “Boar Gore”). The mesentery is transparent, contains varying amounts of fat, and serves as a conduit for blood vessels and nerves supplying the small intestine. Image I shows the transparent mesentery (black arrow) in a living person; red lines are blood vessels flanked on each side by cream-colored fat. Although adjacent to blood vessels, nerves cannot be discerned in this image.

Image I

Image J is a graphic showing intestinal mesentery (yellow). A black arrow marks the duodenojejunal junction/flexure where duodenum (covered by mesentery) meets jejunum – “You had me at hello!” The mesentery anchors jejunum and ileum to the posterior abdominal wall keeping them under control. If bowel is allowed to twist on itself, its blood supply is lost and the bowel will become necrotic (die). Yikes!

Presented with some 19’ of coiled jejunum and ileum in a dissection, it is hard to ken if a loop heads north or south! A down and dirty way to quickly decide whether a loop points toward duodenum or toward large intestine is to grasp loops between two hands and lift like a bouquet of flowers – the root of mesentery is immediately visible allowing one to determine orientation. Don’t try this at home!!! <G>

Image J

Image J

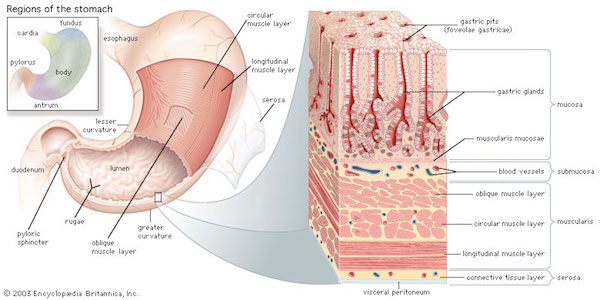

Mucosa: You recall mucosa from earlier GI Tract lessons? Sure, you do! This tissue layer lines the GI tract lumen (central space) from mouth to anus. Mouth mucosa is flat and smooth (excepting tongue) but, such is not the case for small intestine! The entire small intestinal mucosa is thrown into various folds, pleats, and indentations, designed to increase surface area for secretion (release) and absorption (uptake).

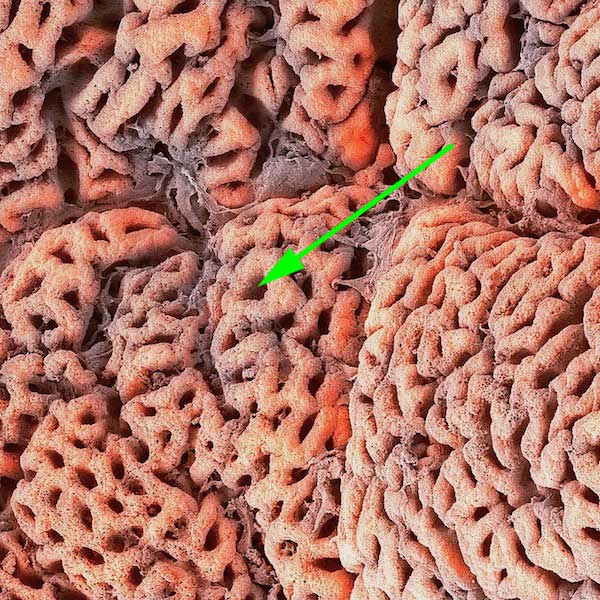

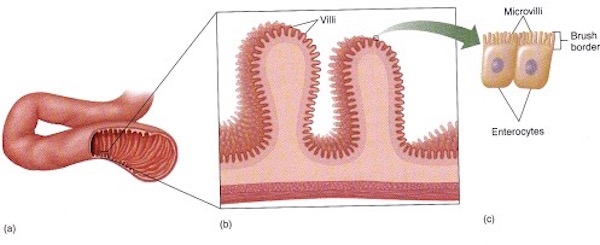

The need for optimal surface area is reflected by a 20’ length; but, this is only the start of amplification! Many circular folds (plicae circulares, Image K – left) enlarge the mucosal surface area. Each plica then supports thousands of villi, wee (0.5 mm) finger-like projections (Image K – middle). Each villus is covered with surface cells (enterocytes) and each surface cell hosts ∼2500 minuscule finger-like projections, the microvilli (Image K – right)!

Considering the 20’ length, plus plicae, villi, and microvilli, the total surface area of our small intestine approaches 2200 ft2 (200 m2), or roughly the floor space of an average US two-story home! Now, that is one fine Fun Fact!

Bottom Line: A gigantic!!! mucosal surface area is required for absorption and secretion which, in turn, is required to sustain each of us.

Image K

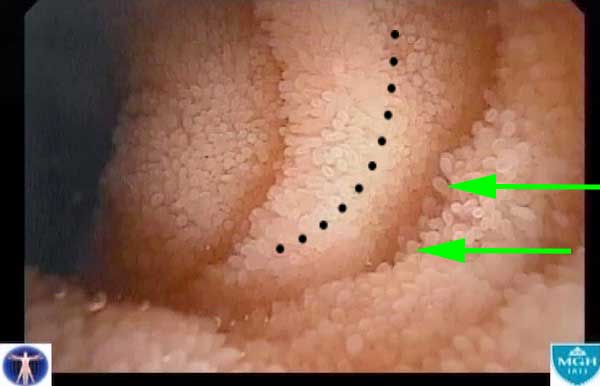

Folds and pleats of small intestinal mucosa are well-demonstrated by magnified endoscopy. Plicae circulares are the large circular folds of mucosa (Image L – black dotted curve). Tiny, finger-like villi (Image L – green arrows) project from the surface of the plicae – millions of them! Cannot see surface cells and microvilli with this technique – waaaay too tiny – the cells, not the technique!

Image L

Some regional differences characterize duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Let’s consider these.

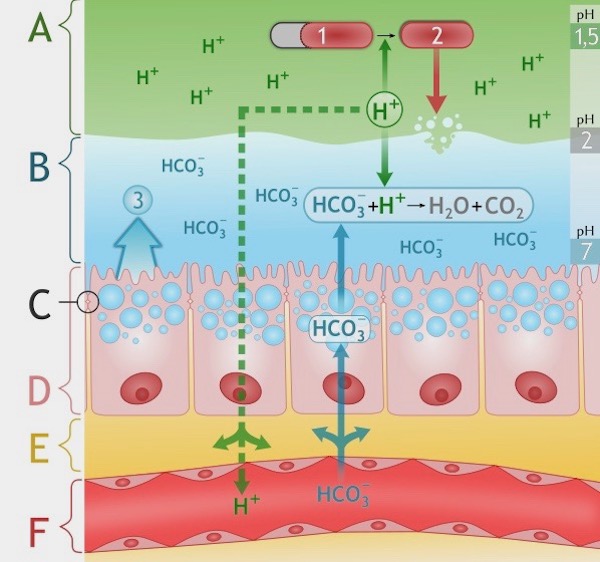

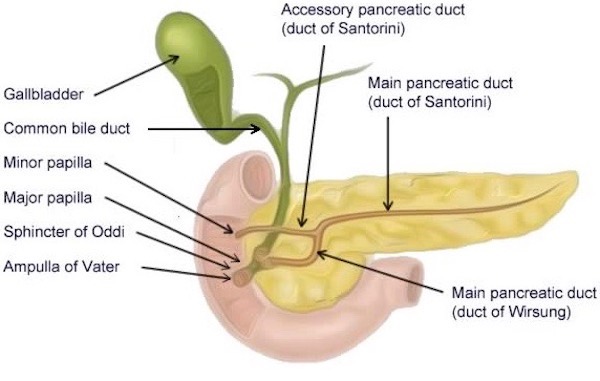

Duodenum: The short duodenum is C-shaped and the pancreas tucks tidily into that curve. Just above the duodenum resides gallbladder and part of liver. This proximity is not an accident as the duodenum receives secretions from pancreas, gallbladder, and liver via ducts (tubes). Its wall also contains a mess of glands releasing alkaline mucus to neutralize highly acidic chyme received from stomach.

The liver makes bile, transports it via ducts to gallbladder where it is stored. If you don’t have a gallbladder, don’t worry, in this situation, bile is released into the duodenum rather continuously.

The pancreas produces digestive enzymes. When stimulated, these products are transported by ducts and released into the duodenal lumen (Image M). A main pancreatic duct fuses with the common bile duct from gallbladder and liver before opening into the duodenum. Most people also have an accessory pancreatic duct. More about pancreas, liver, and gallbladder in a future lesson.

Details! Details! Just so you know… Image M is a great graphic but, the common bile duct is mislabelled because, unfortunately, its black arrow points to the cystic duct. The common bile duct is further along that green tube closer to its union with the main pancreatic duct. Isn’t that a wee bit fussy, doc? Naw! Understand that such details could save a person’s life or limb at some point in time.

Image M

Jejunum: Jejunum has fewer specializations than duodenum and ileum. We can tell where it starts because of the suspensory ligament at the duodenojejunal junction, but where does it ends??? Well, is done best by identifying ileum. Once that has been accomplished, then the segment between ileum and the suspensory ligament is jejunum!

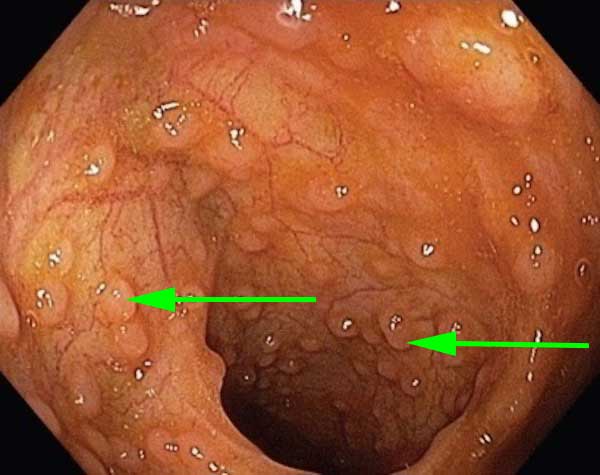

Ileum: Differences between ileum and jejunum are subtle but detectable. Ileum is slightly smaller with thinner walls than jenunum. Its mesentery contains more fat. But the best sign is the presence of numerous nodules in its walls. These bumps are Peyer’s patches and yes, they are normal (Image N – green arrows), although they are more prevalent in the young.

Image N

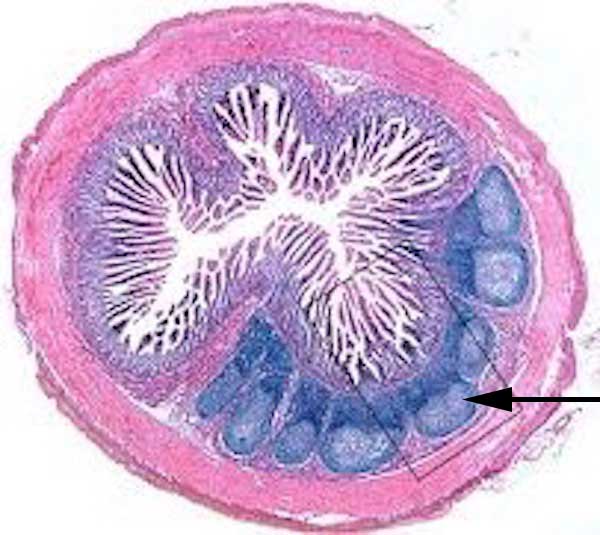

Peyer’s patches were first described by 17th century Swiss anatomist, Johann Conrad Peyer. These nodules are a type of lymphoid tissue, clusters of lymphocytes (and other cells), actively involved in gut immunity. You may notice that these resemble lymphoid tissues of tonsils (Anatomy Lesson #45, “Tremendous Tube – GI System, Part 2”). By microscopy, they appear as blue circles (spheres in 3-dimensions) with dark blue rims and pale centers – typical of lymphoid tissue (Image O – black arrow). Oh, the long, finger-like structures projecting into the lumen are villi, see in 2-dimensions!

Image O

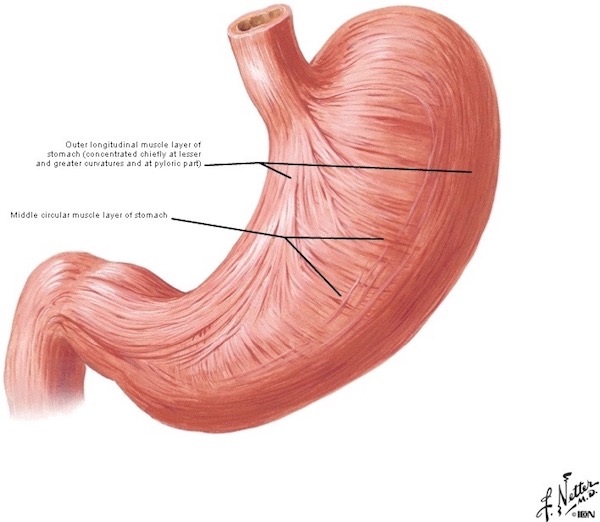

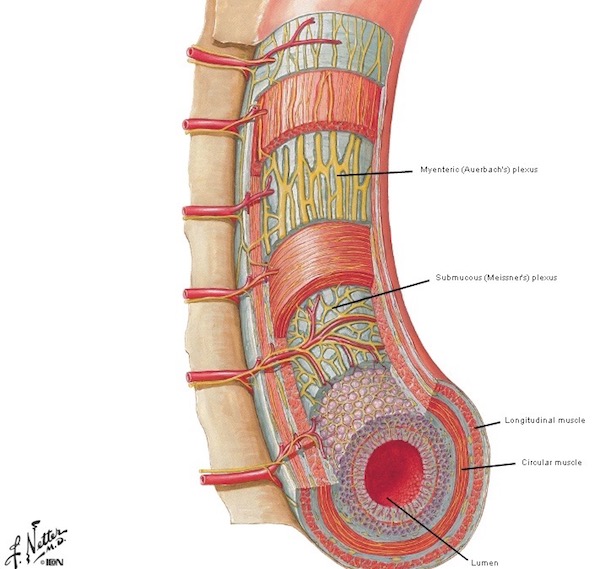

Peristalsis: Coordinated waves of contraction in the walls of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum push chyme towards the large intestine. Such contractions are performed by smooth (involuntary) muscle concentrated in two major layers (Image P): inner circular and outer longitudinal. The autonomic (involuntary) nervous system (and hormone-like substances) stimulate the muscle layers to contract in highly coordinated waves.

Astonishing Fact: The intestinal wall is richly endowed with nerve plexuses (networks) that aid smooth muscle contraction and gland secretion (Image P – yellow networks). Studies now show that our gut contains as many neurons (nerve cells) as our spinal cord, prompting some anatomists to lobby for gut nerve networks to acquire status as a third division of the nervous system. Go gut! Rah!

Image P

Borborygmi: Time for an Outlander connection! This odd word comes from the Greek borborygmós meaning intestinal rumblings, gurgles, and growls, and is likely an onomatopoeia as the spoken word most certainly sounds like the action it describes.

Borborygmi (borborygmus – sing.) occurs as peristalsis moves air and food through the intestine. Hunger, gas, nausea, vomiting, or incomplete digestion of food (think glucose intolerance), all contribute to borborygmi sounds. These sounds, a.k.a. bowel sounds, are amplified via a stethoscope. Clinicians listen for bowel sounds to assess bowel activity; in general, their absence is not a good sign.

Thanks to our fav author, Diana, borborygmi appears in The Fiery Cross:

“What are ye doing out here wi’ wee Phillip Wylie?” Jamie asked, picking his way through a flock of house slaves, who streamed past from the cookhouse with platters of food steaming alluringly under white napkins. “Looking at his horses,” I said, putting a hand over my stomach in hopes of suppressing the resounding borborygmi occasioned by the sight of food. “And what have you been doing?”

You must read The Fiery Cross to find out what Claire was doing in the stable with Mr. Wylie! ?

As for an image, this is the closest we have for now. I wager Claire’s intestines were making borborygmi in this scene from Starz, ep. 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul! Jamie says he never expected to see her puking her guts out over the side of a ship and compliments her complexion by telling her she looks like green fish. Does she need a bucket? Well, she didn’t until he said that!!!

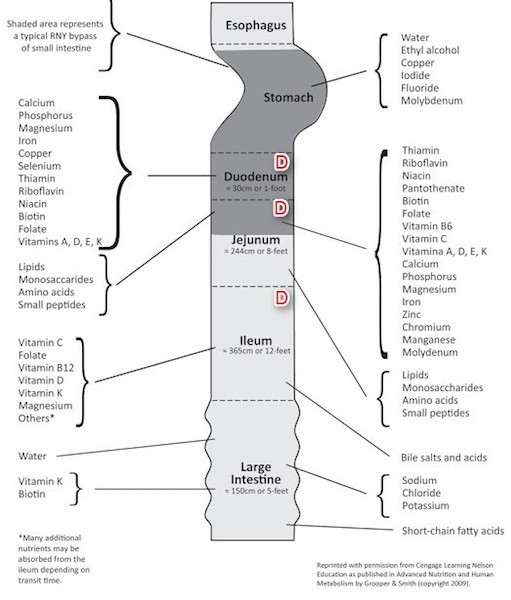

Absorption and Secretion: Arguably, the most important task performed by small intestine is absorption of food stuffs, water, and other molecules needed for life. What do the different parts of small intestine absorb? Well, check out the list in Image Q. The array of ions, nutrients, vitamins, minerals plus water absorbed by duodenum, jejunum, and ileum is staggering!

Although not shown in Image Q, small intestine also secretes lots of mucus which helps move luminal contents during peristalsis, hormones or hormone-like substances that control various gut functions and enzymes which help control gut flora.

Can we lose small intestine and survive? Depends. We can live after removal of duodenum, or most of jejunum, or part of ileum, but it isn’t easy. Such surgery creates many problems and, afterwards, some sufferers may require total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Image Q

Interesting Intestinal Musings: Think of these as mental borborygmi, ha!

In 1620, Scottish medical student John Moir recorded the following “joke” made by his prof:

Intestines are comparable to a jester, who, unless gravely insulted, remains equatable.

Jester? I’ve had a few of those in class. <G> I guess you had to be there. Fair and impartial intestines? Yep, unless something upsets them and then, all hell breaks loose (so to speak)!

In 1535, Spanish physician, Andreas de Laguna wrote this amusing comparison and the basis for yesterday’s teaser:

Indeed the intestines are rightly called ships since they carry the chyme and all the excrement through the entire region of the stomach as if through the Ocean Sea.”

… “those tall ships which as soon as they have crossed the ocean come to Rouen with their cargoes on their way to Paris but transfer their cargoes at Rouen into small boats for the last stage of the journey up the Seine.

“Tall ships” compared to intestines and movement of “cargo” and a final destination up the Seine? Hah! Certainly NOT a reference to our fav production company! (Hope Maril doesn’t read this!).

Small intestine basics are a wrap so let’s close with some fun stuff! Humans can be pretty weird. There’s quite an array of things that creative folks have done to honor small intestine:

#1. Philosophical and Religious Reference: Ever realize the intestines were responsible for human prejudices (Image R). Who knew? Apparently, Nietzsche did. Maybe some concentrated prune juice would cure most prejudices? One can dream!

Image R

#2. Knit Picking: Knitters even hopped on the knitting bandwagon to create large and small bowels! Actually, this is a “darn good yarn” of small intestine (Image S – tan) and large intestine (Image S – green).

Image S

#3. Body Suits: Ran out of costume ideas? Consider a body suit to wear under a sheer dress or to costume party (Image T). Not quite anatomically correct but not all that bad, either – the designer took some liberties with large intestine; that drooping section below the small intestine doesn’t exist in humans!! <g>

Image T

#4 Sox Anyone? Best wash these maroon babies alone unless you want your tidy whities turning blushing pink. Personally, I wouldn’t be caught dead in these!

Image U

#5 Casings: About 4,000 B.C., sausage casings from stomach were made by the Sumerians. Today, most natural sausage casings are made from small intestine. The lumen is cleaned (well, let’s hope so!), mucosa is stripped away, and fat removed, leaving the outer wall to be stuffed. Image V shows the technique. Ah, wait! That looks an awful lot like a, um, er, weil! Which reminds me – the earliest condoms were made of intestine and linen and urinary bladder and fine leather, etc. Leather? Ouch!!! Har, har!

Image V

#6 More Food: Around Hallowe’en, creative souls have baked “small intestine” dishes, puff pastries designed to emulate small intestine. Some are stuffed with sweets similar to mince meat, others are savory similar to sloppy joe’s, and a Greek version is filled with cheese. Intestinal puff pastries are verra popular on the Eve of All Hallows!

Image W

#7 Jewelry: Finally, the last and my favorite, is jewelry (Image X)! Yes, this sterling silver pendant will signal to the world your fav body part: coils of small intestine framed by large intestine, complete with its own anal canal. Charming! What more could a devoted anatomists ask for? Gah!

Image X

Concluding today’s lesson, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!”, with this little nitty-gritty, witty-ditty:

Don’t be depressed in,

If there is unrest in,

There’s always a mess in,

The intestine.

Stuff aggresses in,

Chyme compresses in,

We digest in,

This intestine,

No duress in,

Much less stress in,

Let us be blessed in

Our intestine!

OK, OK, it’s a lame, but the year is young and finding words that rhyme with intestine is rough and tough!

Next lesson is large intestine. Hope to see you there!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Karmen L. Schmidt, Ph.D.

Photo creds: Starz, “Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy,” 4th edition (Image D, E, P), www.agenciacultiva.com (Image G, jejunum), www.anatomybox.com (Image O, PP histology), www.anatomicalelement.com (Image X, pendant), www.archive.cnx.org (Image A, Human intestines, parts colored green and orange; small intestine parts color coded, Image F color coded small intestine), www.ashidashi.com (Image U, sox), www.avetsguidetolife.blogspot.com (Image I, mesentery), www.azquotes.com (Image R, Nietzsche), www.bencuervas.com (Image S, knitting), www.ddc.musc.edu (Image M, duodenal ducts), www.dkfindout.com (Image B, blue whale), www.fabulouslyfrugal.com (Image W, puff pastry), www.javiciencias.blogspot.com (Image L villi), www.mayoclinic.org (Image J root of mesentery), www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov (Image H, ileum), www.openi.nim.nih.gov (Image N, PP endoscopy), www.pinterest.com (Image C, human intestines, parts labelled), www.slovakcooking.com (Image V, casings), www.socratic.org (Image K mucosa), www.thefashionspot.com (Image T, body suit), www.vitamindwiki.com (Image Q, gut absorption)