Uh, oh, puir Lt. Jeremy Foster! His liver said “hello” to Dougal’s dirk! Tomorrow is Anatomy Lesson #49: “Our Liver – The Life Giver!” (Well, except when Uncle Dougal’s around…)

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Human Anatomy taught through the lens of the Outlander books by Diana Gabaldon and the Starz television series

Uh, oh, puir Lt. Jeremy Foster! His liver said “hello” to Dougal’s dirk! Tomorrow is Anatomy Lesson #49: “Our Liver – The Life Giver!” (Well, except when Uncle Dougal’s around…)

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

By Dr. Karmen L. Schmidt

Greetings fellow travelers! Welcome to today’s Anatomy Lesson #48, “The Big Guy,” better known as large intestine. Much is known about large intestine but today’s lesson covers only a tad; otherwise, the lesson would rival one of Diana’s big books! <g> This topic may prove uncomfortable for some, but I hope you lasso any reservations and read this fascinating stuff. For those not sure, Jamie appears to give a wee warning before the most – ahem – personal bits. The good news: Outlander quotes, scenes, and book spoilers await. Yay!

Last lesson, Anatomy Lesson #47, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!” – GI Tract, Part 4, we learned that small intestine ends after ileum, the site where large intestine begins.

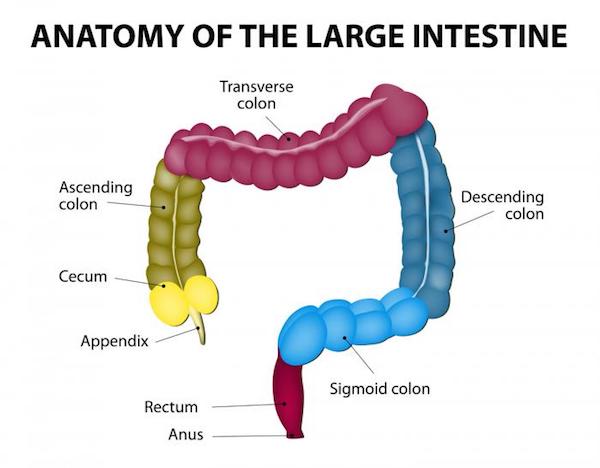

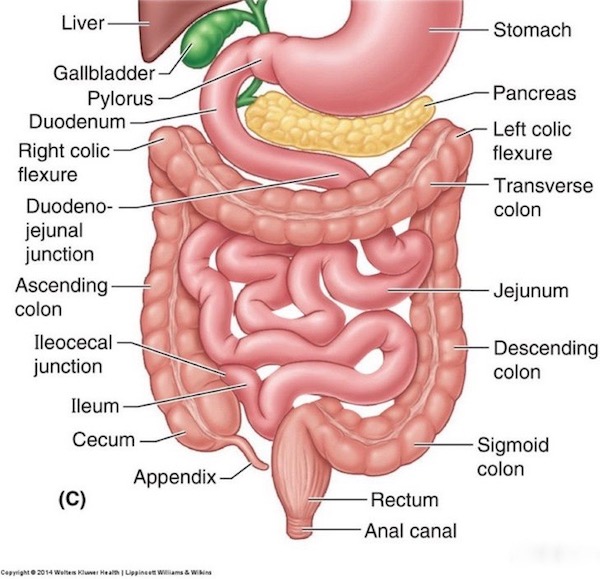

Divisions: As always, anatomical descriptions and definitions are a must! Large intestine is shorter (5 ft) than small intestine (20 ft) but its diameter is larger (3”) compared with the little guy (1-2”), hence the name. Large intestine is divided into the following regions (Image A):

Image A

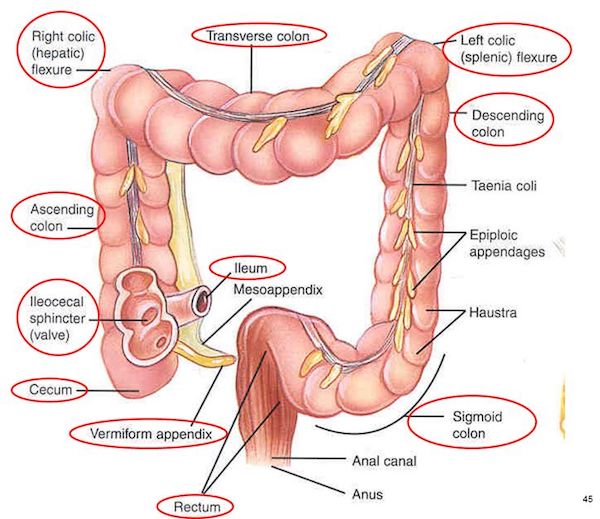

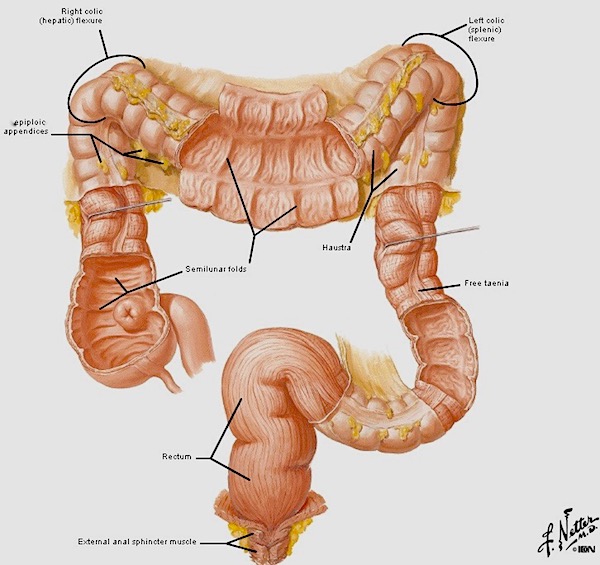

Other Features: Large intestine also exhibits three other important anatomical features (Image B):

Image B

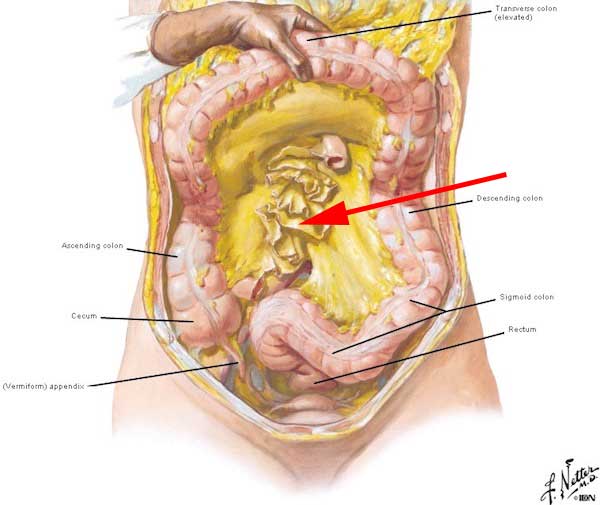

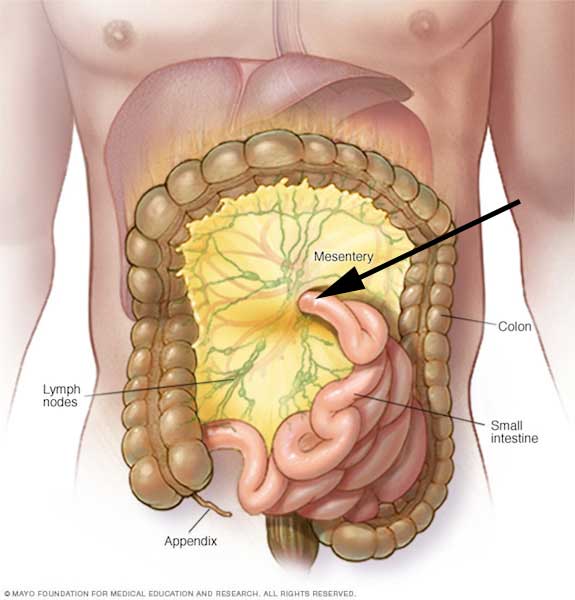

Location: Large intestine lies in the abdominal cavity partially covered by small intestine. Removing small intestine requires cutting the root of the mesentery (Image C – red arrow) – this mesentery suspends small intestine from the posterior abdominal wall (Anatomy Lesson #47, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!” – GI Tract, Part 4).

Now, lifting greater omentum and transverse colon reveals all parts of the large intestine, except anal canal (Image C). The mesentery (yellow in Image C) envelopes most of large intestine, securing the parts in their respective positions and containing blood and nerve supplies. Appendix, cecum, and ascending colon typically sit on the right side of the abdominal cavity – descending and sigmoid colons are on the left. Transverse colon hangs between right and left colic flexures. Rectum lies in the midline of the pelvic cavity.

Understand that exceptions to this arrangement do occur. One rare congenital condition, situs inversus totalis, happens once in every 10,000 people. Here, all abdominal and chest organs are flipped 180°. So, for example, appendix lies in lower- left abdominal cavity. Competent health practitioners must keep such rarities in mind while assessing patients.

Image C

Now, onto specific parts of large intestine.

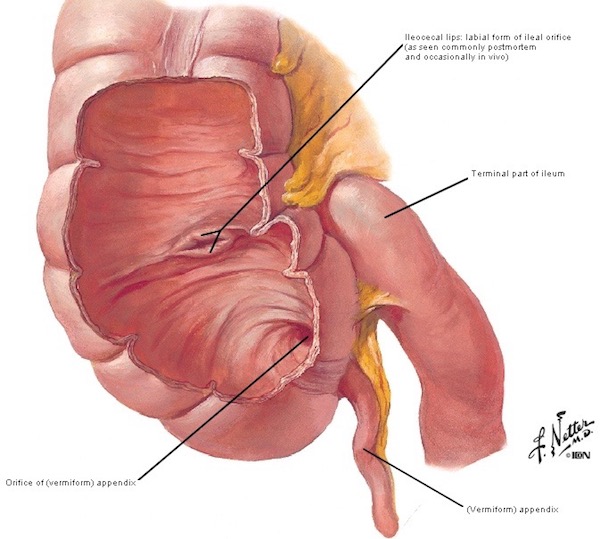

Cecum: The term, cecum or caecum (British spelling), comes from the Latin caecus, meaning blind: not as in sightless, but as in cul-de-sac. The cecum is an enlarged pouch typically located on the right side of the abdominal cavity and is the first part of large intestine. Both appendix and ileum open into the cecum (Image D).

Cecum and ileum are separated by an ileocecal valve, a slit-like opening in the cecal wall. The valve contains a sphincter of smooth muscle, opening to admit chyme from the ileum, and closing to prevent back flow. Thus, cecum serves as a receptacle for fluid chyme.

Image D

History Detour: Almost simultaneously, the ileocecal valve was described by Dutch physician, Nicholaes Tulp, and by Swiss botanist, Gaspar Bauhin. Depending on which scientist one intends to honor, the iliocecal valve is also either the Tulp valve or the Bauhin valve. Yep, the way the world works!

In case you forgot or haven’t read Anatomy Lesson #34, “The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy,“ Tulp is the anatomical demonstrator in Rembrandt’s 1632 painting (Image E), “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.” Several modern anatomists have performed dissections trying to recreate the left forearm tendons as depicted in the painting, but to no avail; the painting is anatomically incorrect, which matters ZIP because it is priceless!

Image E

Pretty cool, eh? Now, back to the lesson!

Vermiform Appendix: The appendix is more accurately termed vermiform appendix, cecal appendix, vermix, or vermiform process. Why use one name when four will do, hah! To improve student vocabulary? No, not really. Adding a second word provides specificity because the body has other appendices (pl.) including those associated with ovary, testis, and colon. Thus, vermiform helps verify which appendix is intended.

I prefer the term vermiform appendix. Why? Vermiform is from the Latin vermes meaning “worms” + formes meaning “shape.” Appendix refers to a process or projection. Voila! A normal vermiform appendix is shaped very much like a long, pink worm!

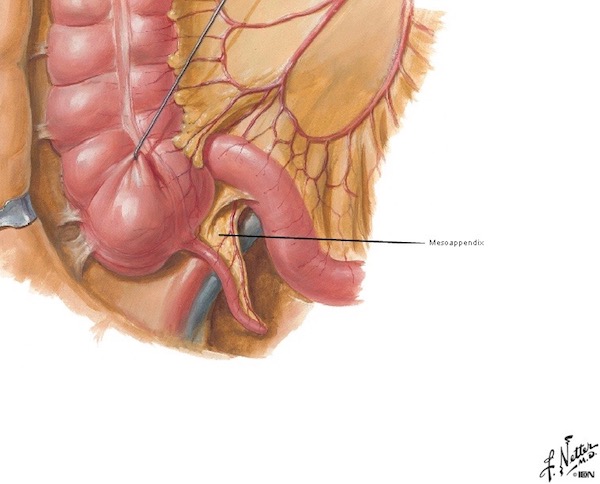

Enough with word roots. Vermiform appendix is a blind-ended, worm-like extension projecting from the cecum and usually located in the lower right abdomen (Image F). It is suspended by a mesoappendix, a fold of mesentery that also provides a conduit for blood vessels and autonomic nerves.

Image F

Appendiceal Location: Illustrations typically place vermiform appendix in the lower right abdominal position, as mentioned above. But, it may assume one of about eight positions relative to the cecum (Image G). Or, a cecum may ride high in the upper right abdominal cavity carrying the vermiform with it, or even shifted to the left side as in situs inversus (Image G). Vermiform appendix may also drift into an inguinal hernia (Image G – red arrow). Interestingly, some alternate appendiceal positions are more prevalent among some populations and cultural groups. Such positional variations can present confusing signs and symptoms and pose diagnostic challenges for practitioners. Truth!

Image G

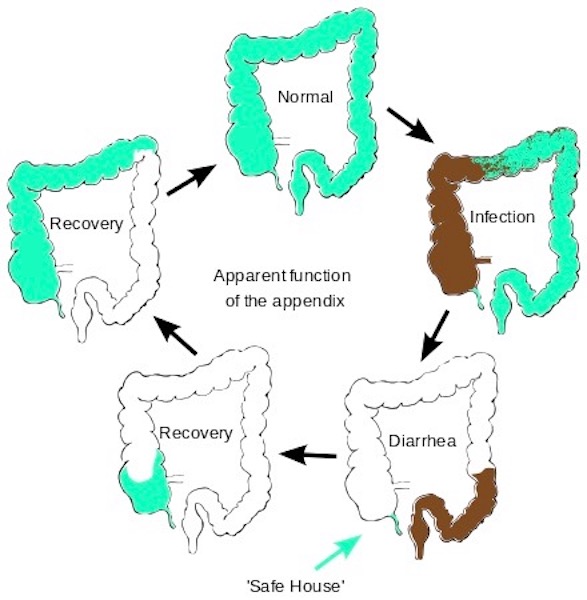

Function #1: The function of vermiform appendix is unclear. Many anatomists consider it a useless relic of an evolutionary past. But, recent studies suggest it acts as a reservoir for good bacteria. After severe diarrhea, the vermiform appendix apparently “reboots” the large intestine by repopulating it with normal bacterial flora (Image H).

I always taught, and still firmly believe, the body doesn’t have useless organs. I reason that if a body part appears useless, it is our own ignorance that impedes understanding. I must confess, though, one savvy student stumped me with the question: “why do men have nipples?” I had no answer then, but I do now – subject for another lesson. Understand, the half-life of medical facts is about 5 years, so new and/or revised info emerges daily! Stay tuned! Hee, hee.

Image H

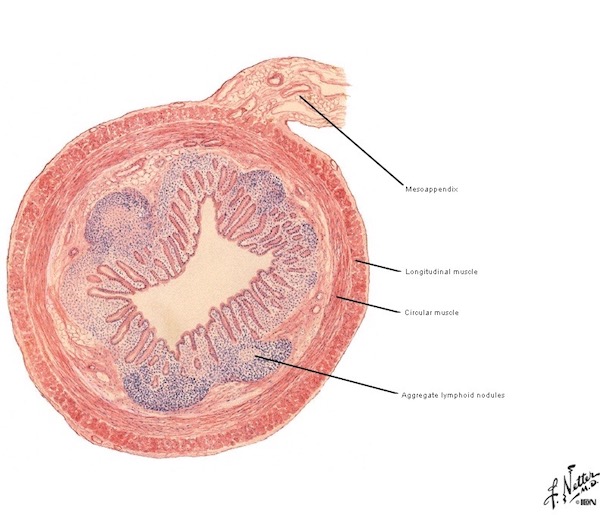

Function #2: Vermiform appendix also serves as a lymphoid organ. Remember the tonsils (Anatomy Lesson #45 “Tremendous Tube” – GI Tract, Part 2) and Peyer’s patches of ileum (Anatomy Lesson #47, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!” – GI Tract, Part 4)? Moving to a microscopic image, these are aggregates of lymphoid nodules (spheres) containing lymphocytes and other cells functioning in immune responses. Turns out the wall of vermiform appendix is loaded with lymphoid nodules (Image I – blue circles with pale centers) which constantly survey luminal proteins to determine which ones are threatening and require an immune response. Cross my heart!

Now, you may argue that vermiform appendix is of dubious value because many people survive without one. My response: well, people can also live without a leg but that doesn’t mean it isn’t useful! Aye?

Image I

Appendicitis: As we learned in Anatomy Lesson #37, “Outlander Owies Part 3 – Mars and Scars,” any anatomical word bearing the suffix “-itis” means inflammation of… Thus, appendicitis means inflammation of the appendix, a condition accompanied by swelling, redness, pain, heat, and loss of function.

Book Spoiler #1: The following quote is from Diana’ sixth big book, “A Breath of Snow and Ashes.” You might skip if you haven’t read it, although the quote doesn’t reveal any plot twists. How did prescient Diana know this lesson needed a quote about appendicitis? One of the great mysteries! <G>

The book describes Surgeon Claire treating a young boy with acute appendicitis. I borrow shamelessly from Starz episode 203, Useful Occupations and Deceptions, to illustrate the quote:

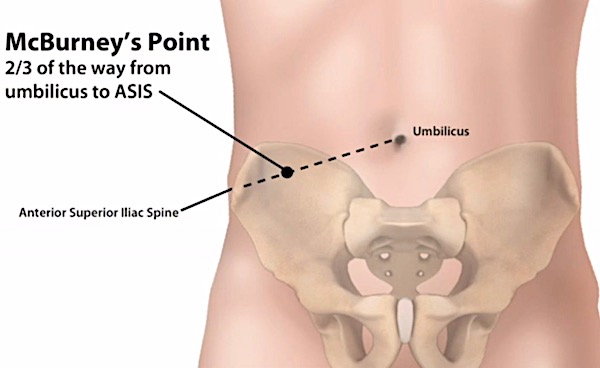

I put a thumb in his navel, my little finger on his right hipbone, and pressed his abdomen sharply with my middle finger, wondering for a second as I did so whether McBurney had yet discovered and named this diagnostic spot. Pain in McBurney’s Spot was a specific diagnostic symptom for acute appendicitis. I pressed Aidan’s stomach there, then I released the pressure, he screamed, arched up off the table, and doubled up like a jackknife. A hot appendix for sure. I’d known I’d encounter one sometime…. No doubt about it, and no choice; if the appendix wasn’t removed, it would rupture.

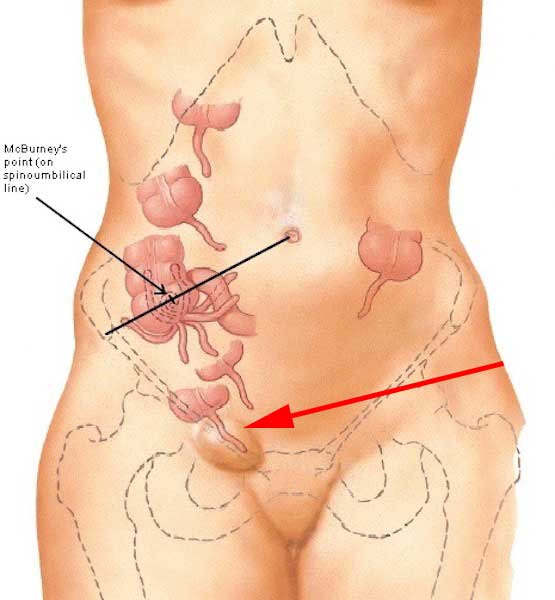

McBurney’s Point: Sounds like a feature of the Scottish coastline <g>, but, its not! McBurney’s Point is the name for a spot on right abdomen that is two-thirds the distance from umbilicus to ASIS, the anterior superior iliac spine of the right hip bone (Anatomy Lesson #39, Anatomy Lesson #39 “Dem Bones – Human Skeleton”). This point roughly corresponds to the most common site where appendix attaches to cecum (Image J). Warning: some descriptions define the point as one-third distance from ASIS to umbilicus. What gives? Going the opposite direction, the latter statement is also true. Do the math!

Try This: Stand before a mirror. Place right fingers over the most prominent bony knob of right hip bone. You know the one – it bumps into corners of tables? Ouch! Now, place right little finger on right ASIS. Place right thumb in navel. Estimate 2/3 distance from thumb to little finger or estimate 1/3 distance from little finger to thumb – this is McBurney’s point! If this is too tough, estimate the halfway point – it will be close. This is likely where the base of your vermiform appendix (if you still have one, of course!) attaches to cecum.

Image J

Back to Appendicitis: And in answer to Claire’s musing, no, McBurney’s point was not described in the 18th century. Who was McBurney? Charles McBurney was an American surgeon who, in 1889, published the relationship between acute appendicitis and McBurney’s point, the typical site of greatest tenderness. Understand, this relationship is not 100% reliable because of appendiceal positional variations and because other abdominal processes may produce tenderness at this site.

Nevertheless, McBurney’s point is significant in three ways:

Back to Dr. Claire and her spot-on description of anatomy and acute appendicitis!

“All right,” I said out loud, triumphant. “Got you!” Very carefully, I hooked a finger under the curve of the cecum and pulled a section of it up through the wound, the inflamed appendix sticking out from it like an angry fat worm, purple with inflammation. “Ligature.” I had it now. I could see the membrane down the side of the appendix and the blood vessels feeding it. Those had to be tied off first; then I could tie off the appendix itself and cut it away. Difficult only because of the small size, but no real problem … “Forceps.” I pulled the purse-string stitch tight, and taking the forceps, poked the tied-off stump of the appendix neatly up into the cecum. I pressed this firmly back into his belly and took a breath.

BTW, the membrane mentioned in the quote is the mesoappendix but you likely figured that out, already. Image K shows what Aiden’s appendix might have looked like after extraction (sans blue terrycloth).

Image K

Moving on…..

Ascending, Transverse and Descending Colons: Most of the length of large intestine is composed of ascending, transverse and descending colon. These parts can be distinguished easily from small intestine because their diameter is larger and they possess these unique features (Image L):

The mucosa (internal lining) of the colon has no villi, the finger-like extensions riddling the mucosa of small intestine. It does exhibit semilunar folds, transverse folds of mucosa that partially encircle the lumen to increase surface area and support stool (feces). The wall of the colon also contains smooth muscle layers which contract to move stool through the lumen.

Colon Functions:

Image L

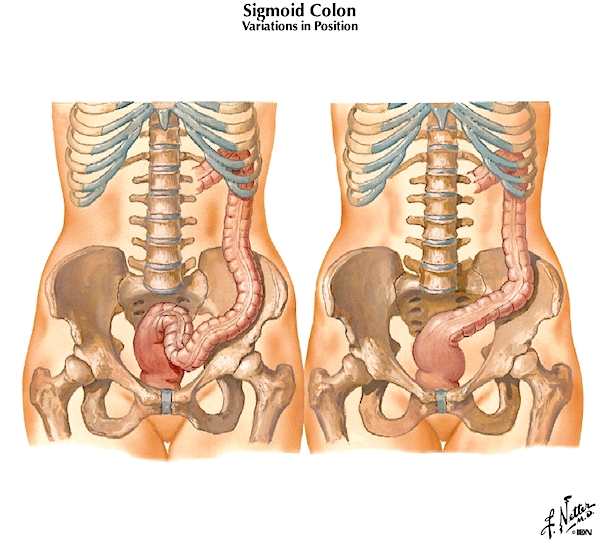

Sigmoid Colon: The sigmoid connects descending colon with rectum. Sigmoid is so named because it is generally S-shaped, although it varies considerably in shape and length! Some of variations are shown in the next two images. Left side of Image M shows a typical sigmoid; right side shows a short, straight sigmoid angling into the pelvis.

Image M

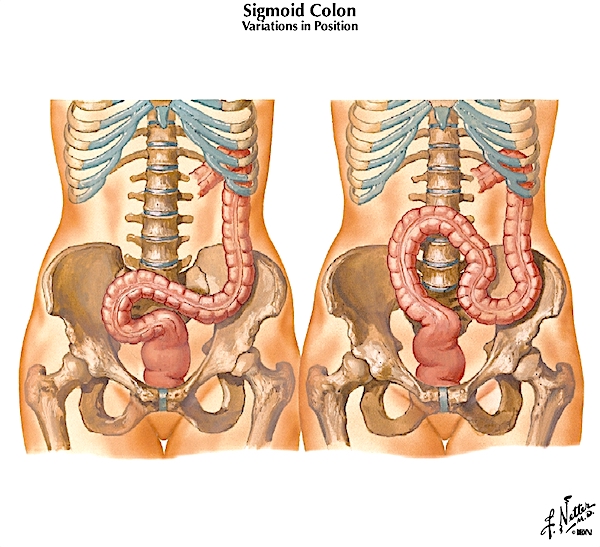

Left side of Image N shows a long sigmoid with a large loop shifted to the right; the right side of the image shows a long sigmoid ascending high into the abdomen. The point is, normal sigmoids assume different shapes, lengths, and positions.

The function of the sigmoid is to accumulate fecal waste until it is ready to leave the body.

This reminds me of a fav saying by surgeons I have worked with: “The good news: there is a light at the end of the tunnel. The bad news: it is a sigmoidoscope!”

Image N

Heeeeeere’s Jamie (Image O) to give you a wee bit of warning! Next up are rectum and anal canal. If these topics cause you discomfort, skip to Jamie and Claire laughing, just before the pelvic floor!

Image O

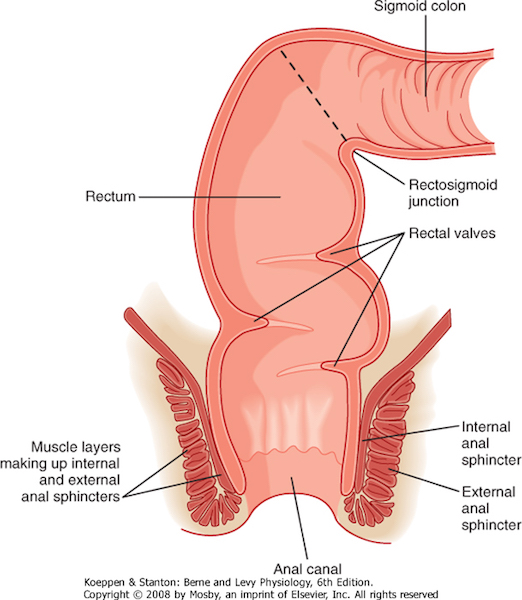

Rectum: The next organ is rectum, the segment between sigmoid colon and anal canal. At its start, the diameters of sigmoid and rectum are the same, but rectum enlarges as it descends into the pelvis (Image P). Many sources define rectum as extending all the way to the anus, but this is not so; rectum converts to anal canal as it passes through the pelvic floor (Image P – black arrow) and anal canal, being a separate part, ends at the anus.

Rectum has no taenia coli or epiploic appendices and it lies in the pelvic cavity, making it easily distinguished from sigmoid. Otherwise, its wall contains smooth muscle and a mucosal lining very much like the rest of large intestine.

The rectum serves as a storage receptacle for feces awaiting release via the anal canal. Rectal valves (Image P) are folds of mucosa that help support stool. During elimination, smooth muscle of the rectal wall contracts to aid defecation. And, rectum releases loads of mucus to aid the movement of stool.

Image P

Och! Here is public proof that many mistakenly believe the rectum reaches all the way to the anus; the so-called rectum bar in Vienna (Image Q) is anatomically incorrect. Who on god’s green earth considered this a viable idea? Would you sample refreshment from such an edifice? Snort!

Image Q

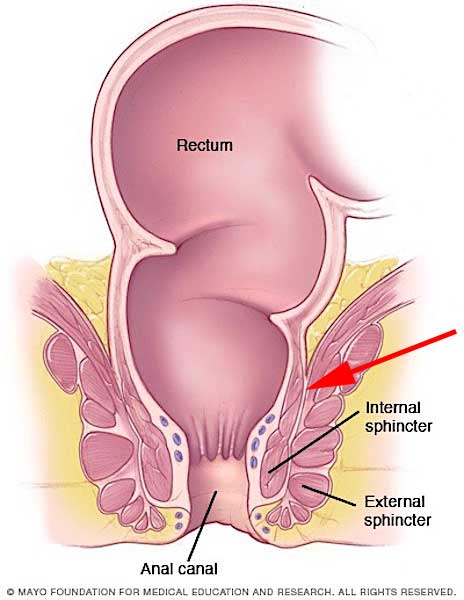

Anal Canal: Last stop! The final segment of large intestine is anal canal (Image R). This complicated structure is pretty short, being only about 1” – 1.5” in length. It begins as rectum traverses the pelvic floor (see below) and ends at the anal verge (anal opening). Its orientation is not vertical, as it is directed downward and backward.

Anal canal is lined with mucosa turning to skin near the anal verge. Its wall contains an internal anal sphincter, smooth muscle over which we exert no voluntary control. Outside the internal sphincter is a sturdy layer of skeletal muscle forming an external anal sphincter, which is controlled voluntarily. Yay!

Normally, both sphincters are tonically contracted but relax during elimination. Psst….a child learns to control the external sphincter during potty training. In most children, this cannot occur until about 18 months due to nerve immaturity. A younger child can be taught to alert the parent when defecation is eminent, but he/she cannot voluntarily control the process.

Image R

Here they are, the cuties! Everybody make it through as far as the pelvic floor?

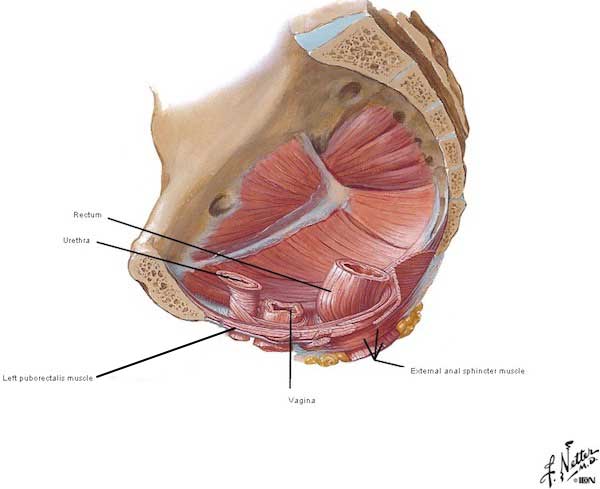

Pelvic Floor: Although not part of large intestine, we must discuss this area because fecal (and urinary) continence requires a healthy pelvic floor. The pelvic floor is formed by the fusion of right and left levator ani muscles forming a muscular diaphragm (we have more than one) that hangs from the bony pelvis much like a hammock (Image S). The floor is pierced by two midline openings in the male, one for urethra and one for anal canal. The female has three midline openings, two the same as a male, plus a middle opening for the vagina (Image S). Each of these openings is supported by levator ani muscles. Although the pelvic floor appears spacious in Image S, in reality it is about the size of half a grapefruit. Very tight squeeze, indeed!

The Way Things Work: A subpart of each levator ani, the puborectalis muscle (Image S) passes backward from each pubic bone to fuse behind the rectum. Forward pull by these paired muscles creates a flexure causing the anal canal to drop downwards and backwards, and thereby closing the channel between rectum and anal canal. During elimination, puborectalis muscles, internal anal sphincter, and external sphincter relax allowing the passage of stool; otherwise, all of these muscles normally remain contracted.

Image S

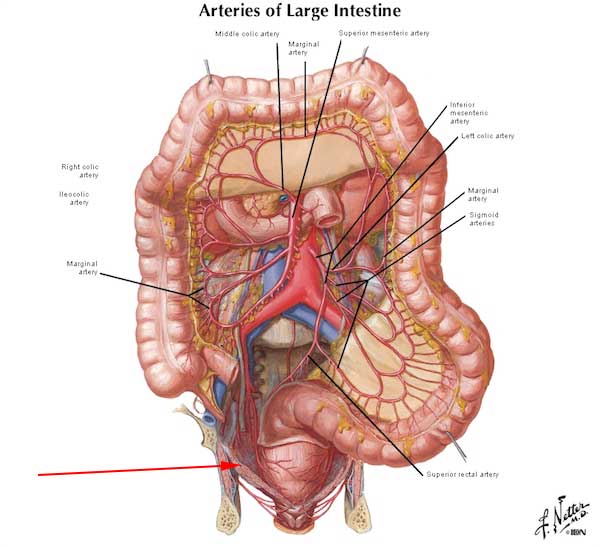

Blood Supply: Like small intestine, large intestine requires a huge blood supply (Image T). Arteries arise from the aorta and its branches supplying all parts of large intestine, from appendix through anal canal. Major arteries also join to form a marginal artery that follows the contour of the large bowel (Image T). Veins follow similar routes.

This prolific blood supply is used for transport of absorbed nutrients, but also provides a huge oxygen supply because bowels are excruciatingly sensitive to oxygen loss. This is why a twisted bowel, bowel loop caught (incarcerated) in a hernia, or other bowel obstruction is of high concern as such events rob bowels of their blood supply and the accompanying cargo of oxygen – these conditions present a medical emergency which must be quickly addressed to avoid bowel death! And, yes, bowel obstructions occur in both large and small intestines. BTW, the red arrow of Image T points to the pelvic floor separating rectum from anal canal.

Book Spoiler #2: From Diana’s third book, Voyager, we read about a patient with a strangulated bowel, caught in a hernia. Too late, the bowel is dead, and Claire is none too happy about it. Again, this quote contains no plot twists, so it might be safe for you to read.

The cause of death was more than obvious: a strangulated hernia. The loop of twisted, gangrenous bowel protruded from one side of the belly, the stretched skin over it already tinged with green, though the body itself was still nearly as warm as life. An expression of agony was fixed on the broad features, and the limbs were still contorted, giving an unfortunately accurate witness to just what sort of death it had been. “Why did you wait?”

Image T

Book Quote: Now, let’s apply some of knowledge gleaned from this lesson. Diana’s second big book, Dragonfly in Amber, describes a horrifying scene wherein Mr. Forez describes to Jamie, the disembowelment of criminals! He hopes to dissuade Big Red from engaging in various occupations and deceptions, no matter how useful. As this scene wasn’t included in the Starz episodes, I’ve used a substitute image of the King’s hangman at L’Hôpital des Anges (Starz episode 204, La Dame Blanche)!

“Just there,” he said, almost dreamily. “At the base of the breastbone. And quickly, to the crest of the groin… —and the letter opener flashed to one side and then the other, quick and delicate as the zigzag flight of a hummingbird—“following the arch of the ribs. You must not cut deeply, for you do not wish to puncture the sac which encloses the entrails. Still, you must get through skin, fat, and muscle, and do it with one stroke. This,” he said with satisfaction… “is artistry.” .. “After that, it is a matter of speed and some dexterity, but if you have been exact in your methods, it will present little difficulty. The entrails are sealed within a membrane, you see, resembling a bag. If you have not severed this by accident, it is a simple matter, needing only a little strength, to force your hands beneath the muscular layer and pull free the entire mass. A quick cut at stomach and anus”—he glanced disparagingly at the letter opener—“and then the entrails may be thrown upon the fire.

Mr. Forez’s description of disembowelment has a few anatomical problems. Scout’s honor. Here’s why:

Truth: Evisceration was designed to keep a convict alive long enough to ensure maximum suffering! So, typically, a short segment of small bowel was pulled through a belly incision, cut out, and thrown on the fire or given to dogs to eat. Thus, the still living victim could gaze with horror at the fate of his own entrails before finally going into shock from blood loss. Vicious prospect. Who thought this one up????

My conclusion for the boo-boos in Mr. Forez’s gory tale is that first, he is not an anatomist, and, second, he deliberately embellished his gruesome story with horrific inaccuracies to halt Jamie’s seditious activities. Of course, this threat didn’t work! Jamie is one stubborn Scot, aye?

So, we now know the structure and functions of the large intestine. Let’s take a few moments to discuss what happens inside the dark tube.

Good Bacteria: We generally think of bacteria as being bad, but in a normal gut, most are good (Image U). Although stomach and small intestine contain relative few species of bacteria, numbers in the large intestine are staggering! More than 1,000 different species of bacteria inhabit the normal large intestine, collectively, that’s trillions of bacteria! Here’s an astonishing factoid: dried feces is 60% bacteria. Yowser!

Image U

Microbiota: Gut flora, collectively known as the microbiota, is a complex community of organisms living mostly in large intestine. Interestingly, our gut flora is established by one to two years of age. Because the gut and its bacteria co-developed, our gut becomes tolerant to, and even supportive of, gut flora. These organisms aren’t just commensal, they are mutualistic, meaning both they and we benefit. Here is what they do for us:

Image V presents a marvelous visual of gut bacteria, a scanning electron micrograph (SEM). It would be great fun if gut bacteria really did come in such marvelous colors, but, no, these are computer generated. The woody-looking slab isn’t for the fireplace; it is a wee shard of dietary fiber!

Image V, SEM by Martin Oeggerli

Western Diet: Now, we could get embroiled in a messy discussion about diet as there is a gut-full of claims floating around in the ethernet. I don’t mean to be a harpist about the western diet (Image W), but 90% of Americans do not know there is a link between diet and cancer!

To the point: Colorectal cancer (bowel cancer) is the second highest cause of cancer deaths, both in the US and in Great Britain! Americans are 13 times more likely to develop bowel cancer than Africans. Thus, in a recent scholarly study, 30 healthy Africans were fed an American diet (high fat, low fiber) and 30 Americans ate an African diet (high fiber, low fat). After two weeks, two weeks I say!, all subjects received a colonoscopy and various tests. Americans on the African diet experienced decreased inflammation and increased production of a fatty acid proven to protect against colon cancer. Africans on the American diet showed increased inflammation and changes that precede the development of cancerous colon cells. This short term study underscores the speed with which an adverse relationship between poor diet and poor colonic health may develop.

Hopefully, you all realize that dietary fiber (roughage) is needed for the large intestine to do it’s job (hee, hee). Fiber helps prevent “traffic jams!” Eating lots of whole grains, legumes, fruits, and veggies aids elimination. Too little dietary fiber coupled with too much fat is a fine recipe for “road blocks!”

Image W

Now, time for some potty talk! Outlander provides, as always…Yep, Diana’s books contain a number of references to beautiful bowels and their dubious duties (Dragonfly in Amber book).

“A verra wearisome business it was, too,” he added, bending over and setting his hands on the floor to stretch the muscles of his legs.

What is wearisome, and whom is Jamie discussing? Why, King Louis of France, of course (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore). Annalise de Marillac does Jamie the dubious honor of hustling him off to observe King Louis perform his morning “rituals” – Murtagh follows, at Claire’s command! The puir man must poop before the entire world. Imagine!

Prof. Jamie explains further in Dragonfly in Amber book:

Took forever; the man’s tight as an owl.” “Tight as an owl?” I asked, amused at the simile. “Constipated, do you mean?” “Aye, costive. And no wonder, the things they eat at Court,” he added censoriously, stretching backward. “Terrible diet, all cream and butter. He should eat parritch every morning for breakfast—that’d take care of it. Verra good for the bowels, ye ken.

This puir King was famously costive because his fat-rich/low-fiber diet resulted in chronic constipation. And, constant straining can balloon the walls of veins draining the anal canal, resulting in hemorrhoids (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore). Truth be told, Lionel Lingelser is one fearless thespian! Hope he was well-paid for this scene; check out the rivulets of sweat streaking his forehead. Oooooh, straining!

Our two “gently-bred” Scots are frankly appalled but they observe the theatrics with manly composure leading Jamie to prescribe peasant parritch for breakfast each morn (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore)!

Who do you think has the worst job? King Louis who must master his bowels before the known universe, or the court physician who must verify his success – or lack thereof (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore)? Hard to say, hah!

Thus “ends” the saga of the GI Tract from lips through anus – it took 5 lessons to cover this tremendous tube!

Let’s close this lesson with a few jokes about large intestine and its duties…. dumb but not too offensive, I hope!

The body is sooo cool! Thus ends the fascinating tale of our large intestine, “The big Guy!” Next lesson, liver and its cohorts!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Karmen L. Schmidt, Ph.D.

PIcture creds: Starz, Atlas of Human Anatomy, Frank H. Netter, M.D., 4th ed. (Images C, D, E, F, G, I, L, M, N, S, T), Medicine Perspectives in History and Art, Robert E. Greenspan, M.D., 2006 (Image E), www.care2.com (Image O), www.enwiki.org (Image H; Image S), www.findchart.com (Image B). www.icanrunaminute.com (Image J), www.lydiaskindfoods.com (Image W), www.mayoclinic.org (Image R), www.medicalnewstoday.com (Image A), www.motherjones.com (Image U), www.ngm.nationalgeographic.com (Image V), www.researchgate.net (Image K), www.sites.google.com (Image P), www.walyou.com (image Q)

By Dr. Karmen L. Schmidt

Have you heard of the word, thairm? Neil Munro in Ayrshire Idylls (1912) writes disparagingly of “The sordid pot of tripe and thairm”. Och! Turns out, this is the Scottish word for intestine, the topic of today’s Anatomy Lesson #47, Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut.” We resume the multi-lesson tour of our fantastic GI Tracts!

The bowels , a.k.a., intestines, gut, guts, entrails, viscera, insides, or innards, are critically important for survival. Times have changed: my parents would not allow their kids to use the word gut, thinking it crass. But, anatomists, especially embryologists, use gut as a scientific term, so, let’s go!

WARNING: Image I is a surgical specimen of human small intestine. If your wame is wobbly, you might eat first!

Our last lesson (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach, Wobbly Wame) informed us that “stuff” enters the stomach as individual boluses (globs) of swallowed food and drink. After mixing with gastric fluids, chyme, an acidic, watery mass is formed and released into the small intestine by controlled opening and closing of the pyloric sphincter.

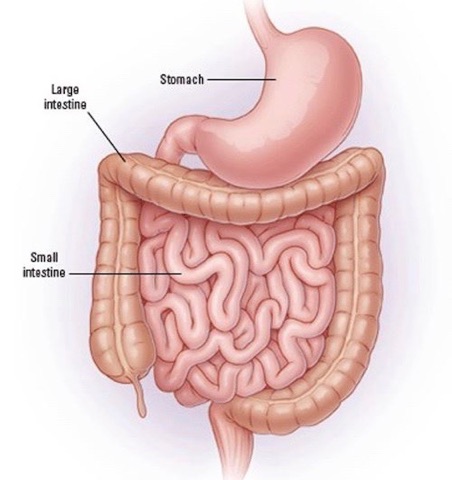

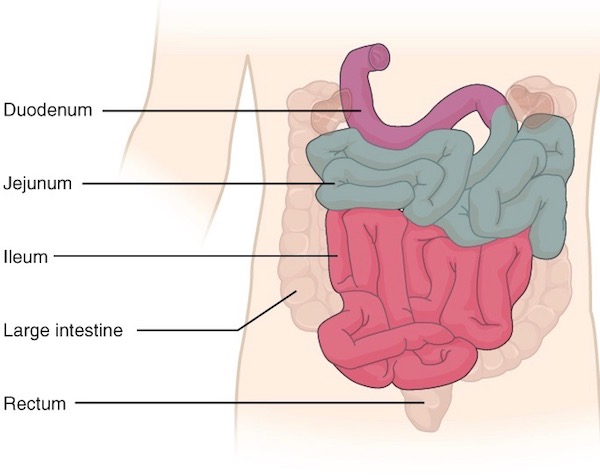

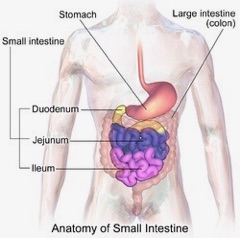

Overview: Our intestine extends from pyloric sphincter (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach – Wobbly Wame) to anus and is divided into small intestine and large intestine (Image A). An adult small intestine is about 20 ft (6 m) long; large intestine is 5 ft (1.5 m). Whoa! If small intestine is longer than the large intestine, then why is it small? Because, the large intestine is wider: 3” diameter compared with 1” for small intestine. Not my fault! <g>

Image A

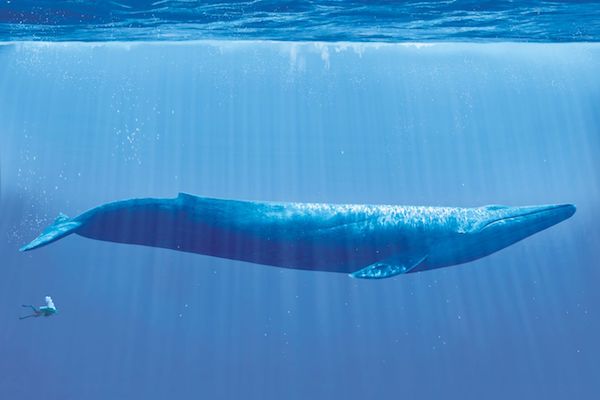

Humble Pie: Our intestines are teenie-weenies compared with those of an adult blue whale (Image B); their small intestine is about 720 ft long! Hum… let’s see, now… a US football field is 360 ft long so, a blue whale’s intestine is twice the length of a football field! And, its diet is composed entirely of wee creatures (krill. etc.). Just sayin’… let us be humble!

Image B

Divisions: Like other body parts, anatomists subdivide intestines based on differences in form and function. Thus, intestines fall into two major segments, small intestine and large intestine both of which have subdivisions (Image C):

small intestine

large intestine (to be covered next lesson!)

Image C

Small Intestine: Ever see a tall man squeeze into a small car? Likewise, the small intestine must adapt its 20’ length to the confines of the abdominal cavity. It does so by folding into loops. Gordie demoed his intestinal loops in Starz episode 104, The Gathering!

Puir Geordie, a boar’s tusk lacerated his anterior abdominal wall (Anatomy Lesson #16, “Jamie’s Belly” or “Scottish Six-Pack”), exposing his innards. Like Dougal, we wept for ye, man…Diana explains Geordie’s dire circumstances in Outlander book:

What couldn’t be stopped was the ooze from the man’s belly, where the ripping tushes had laid open skin, muscles, mesentery, and gut alike. There were no large vessels severed there, but the intestine was punctured; I could see it plainly, through the jagged rent in the man’s skin. This sort of abdominal wound was frequently fatal, even with a modern operating room, sutures, and antibiotics readily to hand. The contents of the ruptured gut, spilling out into the body cavity, simply contaminated the whole area and made infection a deadly certainty. And here, with nothing but cloves of garlic and yarrow flowers to treat it with.…

Verra sad.

Psst…. Pig entrails may have been used in ep 104, as the diameter looks a bit wide for human small intestine, but convincing, none the less. Congrats, to the Outlander special effects team!

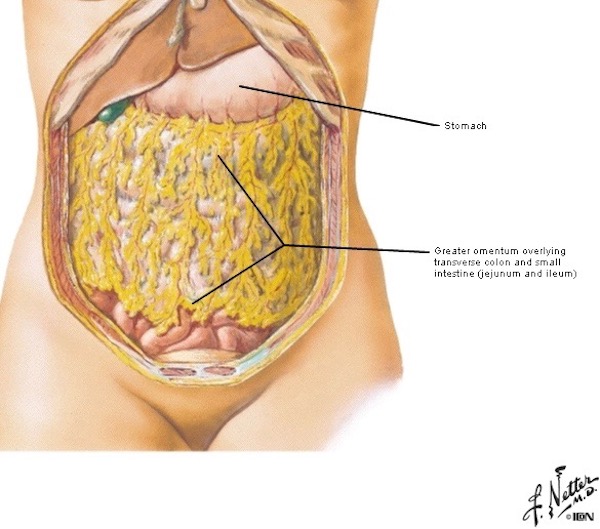

Opening the body wall, does not usually reveal much small intestine (Image D) because most of it is covered by the fat-filled greater omentum, hanging from the greater curvature of stomach (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach – Wobbly Wame).

Image D

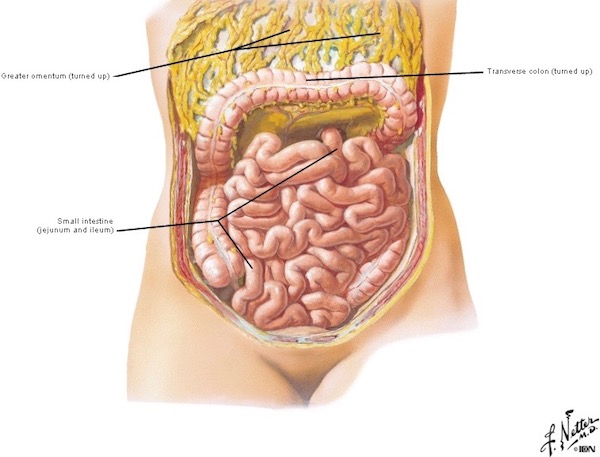

Lifting stomach, transverse colon (part of large intestine), and greater omentum toward the head reveals coils of small intestine (Image E) nestled in the abdominal cavity. When standing, some loops typically slip into the pelvic cavity. See that although jejunum and ileum are labelled in Image E, duodenum is not because it lies at a deeper level (described below).

Image E

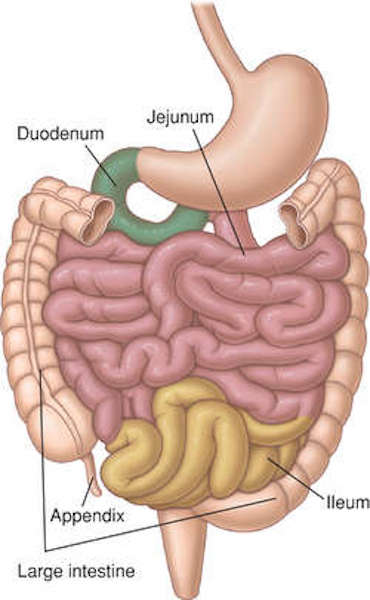

As noted above, small intestine is divided into three regions from proximal (near end) to distal (far end): duodenum, jejunum, and Ileum – let’s examine each part.

Duodenum: Only by moving large intestine and removing a mesentery (membrane) is the duodenum exposed.

Just so you ken, the word duodenum is pronounced du·o·de·num (four syllabi), not, du·ode·num (three syllabi). The word comes from the Latin duodeni meaning “in twelves.” Why? Because the length of duodenum roughly equals the breadth of 12 adult fingers ~ 1 ft, some 15% of the overall length of small intestine.

Try this: Lay hands side-by-side and imagine two more fingers added at one end. That’s the length of duodenum. Got it? Grand!

Duodenum (Image F – purple) starts at the pyloric sphincter of stomach and ends at the jejunum (Image F – green). Also, notice it assumes a C-shaped curve which has an important purpose – we will return to this feature later.

Image F

Jejunum: Jejunum comes from the Latin word jējūnus meaning empty or fasting; so named because it was often empty of food after death. The duodenum abruptly ends at a flexure created by a suspensory structure (ligament of Treitz), the spot where jejunum begins (not shown in Image G).

Jejunum makes up 8 ft (38%) of the small intestine (Image G – pinkish) and ends at start of ileum (Image G – yellow).

Image G

Ileum: Ileum (Image H – hot purple) is the longest and terminal part of small intestine, some 13 ft in length (47% of small intestine). Ileum comes from the Greek word, eilein, meaning to twist up tightly; the coiled ileum certainly gibes with its word root! It ends at the cecum, part of the large intestine.

Image H

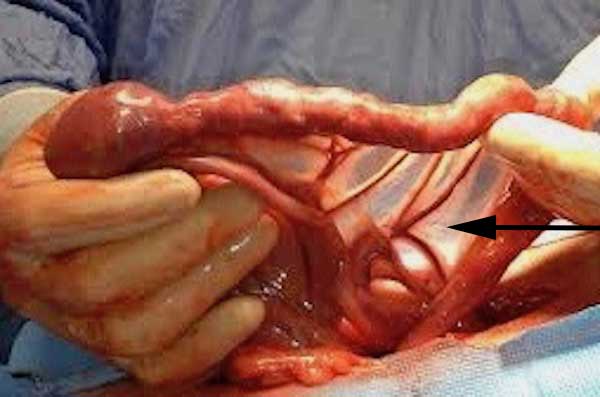

Small Intestine Mesentery: You might think that small intestine slips willy-nilly around the abdominal cavity, but that is not so. Although intestinal coils do move, they are anchored by mesentery, part of the peritoneal lining of the abdominal cavity (Anatomy Lesson #9, “The Gathering” or “Boar Gore”). The mesentery is transparent, contains varying amounts of fat, and serves as a conduit for blood vessels and nerves supplying the small intestine. Image I shows the transparent mesentery (black arrow) in a living person; red lines are blood vessels flanked on each side by cream-colored fat. Although adjacent to blood vessels, nerves cannot be discerned in this image.

Image I

Image J is a graphic showing intestinal mesentery (yellow). A black arrow marks the duodenojejunal junction/flexure where duodenum (covered by mesentery) meets jejunum – “You had me at hello!” The mesentery anchors jejunum and ileum to the posterior abdominal wall keeping them under control. If bowel is allowed to twist on itself, its blood supply is lost and the bowel will become necrotic (die). Yikes!

Presented with some 19’ of coiled jejunum and ileum in a dissection, it is hard to ken if a loop heads north or south! A down and dirty way to quickly decide whether a loop points toward duodenum or toward large intestine is to grasp loops between two hands and lift like a bouquet of flowers – the root of mesentery is immediately visible allowing one to determine orientation. Don’t try this at home!!! <G>

Image J

Image J

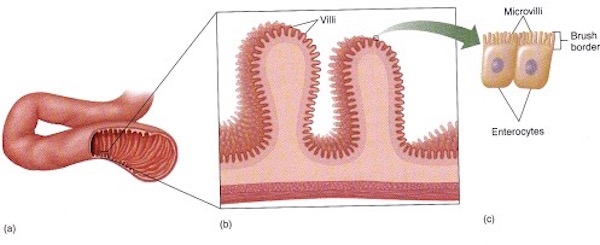

Mucosa: You recall mucosa from earlier GI Tract lessons? Sure, you do! This tissue layer lines the GI tract lumen (central space) from mouth to anus. Mouth mucosa is flat and smooth (excepting tongue) but, such is not the case for small intestine! The entire small intestinal mucosa is thrown into various folds, pleats, and indentations, designed to increase surface area for secretion (release) and absorption (uptake).

The need for optimal surface area is reflected by a 20’ length; but, this is only the start of amplification! Many circular folds (plicae circulares, Image K – left) enlarge the mucosal surface area. Each plica then supports thousands of villi, wee (0.5 mm) finger-like projections (Image K – middle). Each villus is covered with surface cells (enterocytes) and each surface cell hosts ∼2500 minuscule finger-like projections, the microvilli (Image K – right)!

Considering the 20’ length, plus plicae, villi, and microvilli, the total surface area of our small intestine approaches 2200 ft2 (200 m2), or roughly the floor space of an average US two-story home! Now, that is one fine Fun Fact!

Bottom Line: A gigantic!!! mucosal surface area is required for absorption and secretion which, in turn, is required to sustain each of us.

Image K

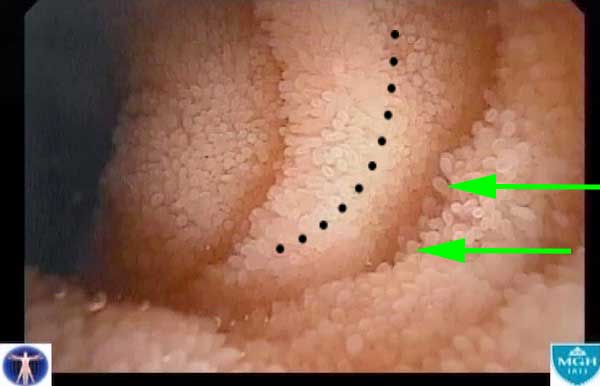

Folds and pleats of small intestinal mucosa are well-demonstrated by magnified endoscopy. Plicae circulares are the large circular folds of mucosa (Image L – black dotted curve). Tiny, finger-like villi (Image L – green arrows) project from the surface of the plicae – millions of them! Cannot see surface cells and microvilli with this technique – waaaay too tiny – the cells, not the technique!

Image L

Some regional differences characterize duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Let’s consider these.

Duodenum: The short duodenum is C-shaped and the pancreas tucks tidily into that curve. Just above the duodenum resides gallbladder and part of liver. This proximity is not an accident as the duodenum receives secretions from pancreas, gallbladder, and liver via ducts (tubes). Its wall also contains a mess of glands releasing alkaline mucus to neutralize highly acidic chyme received from stomach.

The liver makes bile, transports it via ducts to gallbladder where it is stored. If you don’t have a gallbladder, don’t worry, in this situation, bile is released into the duodenum rather continuously.

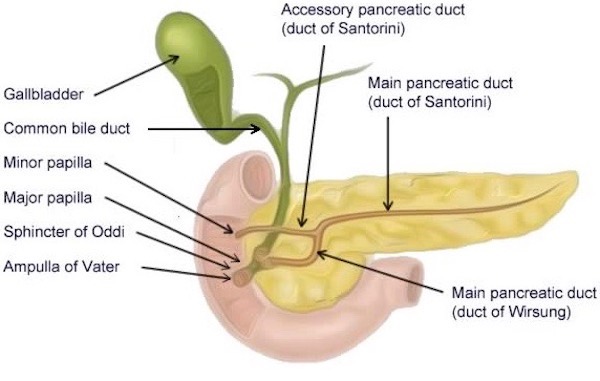

The pancreas produces digestive enzymes. When stimulated, these products are transported by ducts and released into the duodenal lumen (Image M). A main pancreatic duct fuses with the common bile duct from gallbladder and liver before opening into the duodenum. Most people also have an accessory pancreatic duct. More about pancreas, liver, and gallbladder in a future lesson.

Details! Details! Just so you know… Image M is a great graphic but, the common bile duct is mislabelled because, unfortunately, its black arrow points to the cystic duct. The common bile duct is further along that green tube closer to its union with the main pancreatic duct. Isn’t that a wee bit fussy, doc? Naw! Understand that such details could save a person’s life or limb at some point in time.

Image M

Jejunum: Jejunum has fewer specializations than duodenum and ileum. We can tell where it starts because of the suspensory ligament at the duodenojejunal junction, but where does it ends??? Well, is done best by identifying ileum. Once that has been accomplished, then the segment between ileum and the suspensory ligament is jejunum!

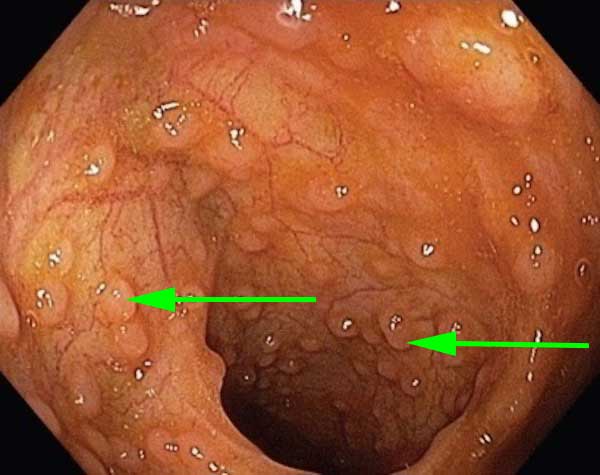

Ileum: Differences between ileum and jejunum are subtle but detectable. Ileum is slightly smaller with thinner walls than jenunum. Its mesentery contains more fat. But the best sign is the presence of numerous nodules in its walls. These bumps are Peyer’s patches and yes, they are normal (Image N – green arrows), although they are more prevalent in the young.

Image N

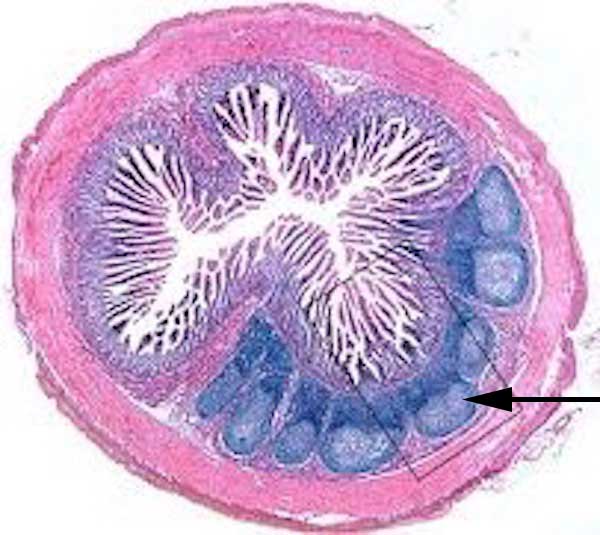

Peyer’s patches were first described by 17th century Swiss anatomist, Johann Conrad Peyer. These nodules are a type of lymphoid tissue, clusters of lymphocytes (and other cells), actively involved in gut immunity. You may notice that these resemble lymphoid tissues of tonsils (Anatomy Lesson #45, “Tremendous Tube – GI System, Part 2”). By microscopy, they appear as blue circles (spheres in 3-dimensions) with dark blue rims and pale centers – typical of lymphoid tissue (Image O – black arrow). Oh, the long, finger-like structures projecting into the lumen are villi, see in 2-dimensions!

Image O

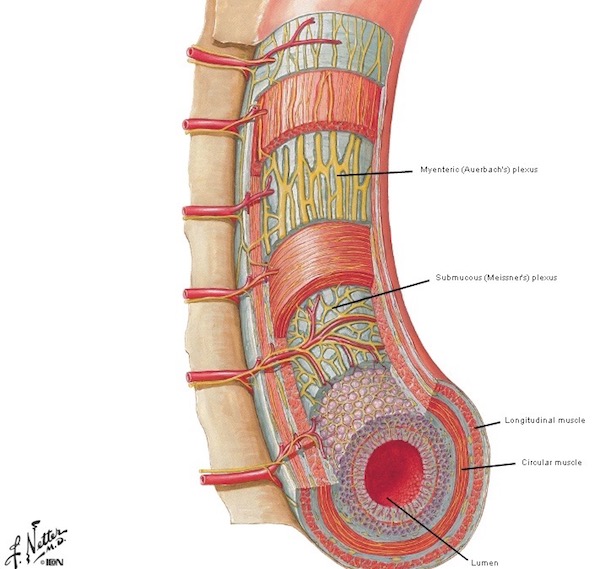

Peristalsis: Coordinated waves of contraction in the walls of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum push chyme towards the large intestine. Such contractions are performed by smooth (involuntary) muscle concentrated in two major layers (Image P): inner circular and outer longitudinal. The autonomic (involuntary) nervous system (and hormone-like substances) stimulate the muscle layers to contract in highly coordinated waves.

Astonishing Fact: The intestinal wall is richly endowed with nerve plexuses (networks) that aid smooth muscle contraction and gland secretion (Image P – yellow networks). Studies now show that our gut contains as many neurons (nerve cells) as our spinal cord, prompting some anatomists to lobby for gut nerve networks to acquire status as a third division of the nervous system. Go gut! Rah!

Image P

Borborygmi: Time for an Outlander connection! This odd word comes from the Greek borborygmós meaning intestinal rumblings, gurgles, and growls, and is likely an onomatopoeia as the spoken word most certainly sounds like the action it describes.

Borborygmi (borborygmus – sing.) occurs as peristalsis moves air and food through the intestine. Hunger, gas, nausea, vomiting, or incomplete digestion of food (think glucose intolerance), all contribute to borborygmi sounds. These sounds, a.k.a. bowel sounds, are amplified via a stethoscope. Clinicians listen for bowel sounds to assess bowel activity; in general, their absence is not a good sign.

Thanks to our fav author, Diana, borborygmi appears in The Fiery Cross:

“What are ye doing out here wi’ wee Phillip Wylie?” Jamie asked, picking his way through a flock of house slaves, who streamed past from the cookhouse with platters of food steaming alluringly under white napkins. “Looking at his horses,” I said, putting a hand over my stomach in hopes of suppressing the resounding borborygmi occasioned by the sight of food. “And what have you been doing?”

You must read The Fiery Cross to find out what Claire was doing in the stable with Mr. Wylie! ?

As for an image, this is the closest we have for now. I wager Claire’s intestines were making borborygmi in this scene from Starz, ep. 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul! Jamie says he never expected to see her puking her guts out over the side of a ship and compliments her complexion by telling her she looks like green fish. Does she need a bucket? Well, she didn’t until he said that!!!

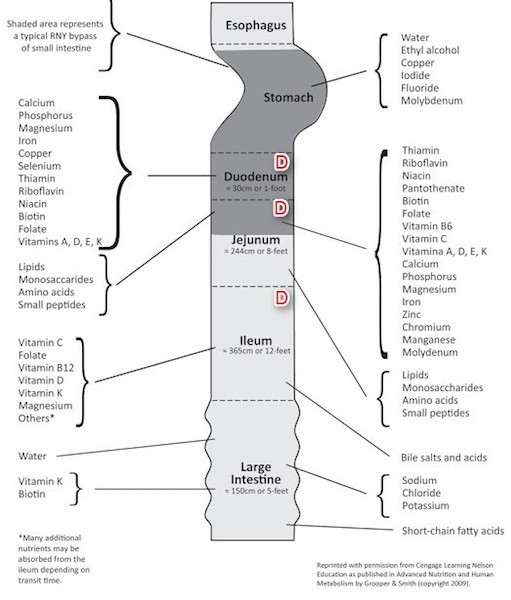

Absorption and Secretion: Arguably, the most important task performed by small intestine is absorption of food stuffs, water, and other molecules needed for life. What do the different parts of small intestine absorb? Well, check out the list in Image Q. The array of ions, nutrients, vitamins, minerals plus water absorbed by duodenum, jejunum, and ileum is staggering!

Although not shown in Image Q, small intestine also secretes lots of mucus which helps move luminal contents during peristalsis, hormones or hormone-like substances that control various gut functions and enzymes which help control gut flora.

Can we lose small intestine and survive? Depends. We can live after removal of duodenum, or most of jejunum, or part of ileum, but it isn’t easy. Such surgery creates many problems and, afterwards, some sufferers may require total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Image Q

Interesting Intestinal Musings: Think of these as mental borborygmi, ha!

In 1620, Scottish medical student John Moir recorded the following “joke” made by his prof:

Intestines are comparable to a jester, who, unless gravely insulted, remains equatable.

Jester? I’ve had a few of those in class. <G> I guess you had to be there. Fair and impartial intestines? Yep, unless something upsets them and then, all hell breaks loose (so to speak)!

In 1535, Spanish physician, Andreas de Laguna wrote this amusing comparison and the basis for yesterday’s teaser:

Indeed the intestines are rightly called ships since they carry the chyme and all the excrement through the entire region of the stomach as if through the Ocean Sea.”

… “those tall ships which as soon as they have crossed the ocean come to Rouen with their cargoes on their way to Paris but transfer their cargoes at Rouen into small boats for the last stage of the journey up the Seine.

“Tall ships” compared to intestines and movement of “cargo” and a final destination up the Seine? Hah! Certainly NOT a reference to our fav production company! (Hope Maril doesn’t read this!).

Small intestine basics are a wrap so let’s close with some fun stuff! Humans can be pretty weird. There’s quite an array of things that creative folks have done to honor small intestine:

#1. Philosophical and Religious Reference: Ever realize the intestines were responsible for human prejudices (Image R). Who knew? Apparently, Nietzsche did. Maybe some concentrated prune juice would cure most prejudices? One can dream!

Image R

#2. Knit Picking: Knitters even hopped on the knitting bandwagon to create large and small bowels! Actually, this is a “darn good yarn” of small intestine (Image S – tan) and large intestine (Image S – green).

Image S

#3. Body Suits: Ran out of costume ideas? Consider a body suit to wear under a sheer dress or to costume party (Image T). Not quite anatomically correct but not all that bad, either – the designer took some liberties with large intestine; that drooping section below the small intestine doesn’t exist in humans!! <g>

Image T

#4 Sox Anyone? Best wash these maroon babies alone unless you want your tidy whities turning blushing pink. Personally, I wouldn’t be caught dead in these!

Image U

#5 Casings: About 4,000 B.C., sausage casings from stomach were made by the Sumerians. Today, most natural sausage casings are made from small intestine. The lumen is cleaned (well, let’s hope so!), mucosa is stripped away, and fat removed, leaving the outer wall to be stuffed. Image V shows the technique. Ah, wait! That looks an awful lot like a, um, er, weil! Which reminds me – the earliest condoms were made of intestine and linen and urinary bladder and fine leather, etc. Leather? Ouch!!! Har, har!

Image V

#6 More Food: Around Hallowe’en, creative souls have baked “small intestine” dishes, puff pastries designed to emulate small intestine. Some are stuffed with sweets similar to mince meat, others are savory similar to sloppy joe’s, and a Greek version is filled with cheese. Intestinal puff pastries are verra popular on the Eve of All Hallows!

Image W

#7 Jewelry: Finally, the last and my favorite, is jewelry (Image X)! Yes, this sterling silver pendant will signal to the world your fav body part: coils of small intestine framed by large intestine, complete with its own anal canal. Charming! What more could a devoted anatomists ask for? Gah!

Image X

Concluding today’s lesson, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!”, with this little nitty-gritty, witty-ditty:

Don’t be depressed in,

If there is unrest in,

There’s always a mess in,

The intestine.

Stuff aggresses in,

Chyme compresses in,

We digest in,

This intestine,

No duress in,

Much less stress in,

Let us be blessed in

Our intestine!

OK, OK, it’s a lame, but the year is young and finding words that rhyme with intestine is rough and tough!

Next lesson is large intestine. Hope to see you there!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Karmen L. Schmidt, Ph.D.

Photo creds: Starz, “Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy,” 4th edition (Image D, E, P), www.agenciacultiva.com (Image G, jejunum), www.anatomybox.com (Image O, PP histology), www.anatomicalelement.com (Image X, pendant), www.archive.cnx.org (Image A, Human intestines, parts colored green and orange; small intestine parts color coded, Image F color coded small intestine), www.ashidashi.com (Image U, sox), www.avetsguidetolife.blogspot.com (Image I, mesentery), www.azquotes.com (Image R, Nietzsche), www.bencuervas.com (Image S, knitting), www.ddc.musc.edu (Image M, duodenal ducts), www.dkfindout.com (Image B, blue whale), www.fabulouslyfrugal.com (Image W, puff pastry), www.javiciencias.blogspot.com (Image L villi), www.mayoclinic.org (Image J root of mesentery), www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov (Image H, ileum), www.openi.nim.nih.gov (Image N, PP endoscopy), www.pinterest.com (Image C, human intestines, parts labelled), www.slovakcooking.com (Image V, casings), www.socratic.org (Image K mucosa), www.thefashionspot.com (Image T, body suit), www.vitamindwiki.com (Image Q, gut absorption)