Welcome Outlander Anatomy readers! Our last lesson covered the human skeleton (Anatomy Lesson #39 “Dem Bones – The Human Skeleton”). Today’s Anatomy Lesson #40, “Snap, Crackle, Pop! or How Bones Heal” expands on bone anatomy but also addresses bone fractures and how they mend. As always, Starz Outlander images and quotes from Diana Gabaldon’s marvelous books are generously sprinkled throughout the lesson.

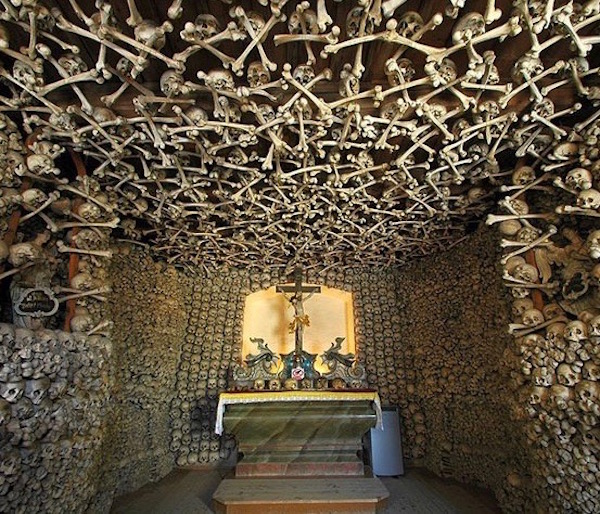

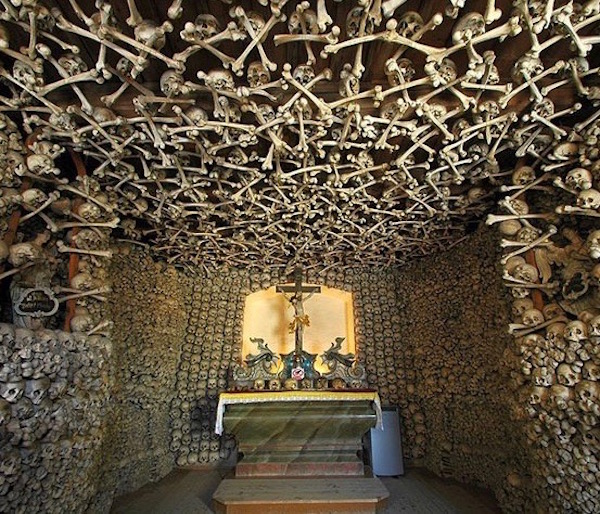

Last lesson began with spectacular images from Master Raymond’s hidden ossuary. This lesson, we start with images of a world famous ossuary located in Kutná Hora, Czech Republic. Known world-wide as the Bone Church, it is an ossuary (‘Kostnice’ in Czech) that houses the bones of an estimated 40,000 – 70,000 people (Image A).

Image A

Here, bones are imaginatively and artistically arranged throughout the edifice. One of the most famous displays is a chandelier, purportedly containing every bone of the adult human body (Image B).

During the thirty years’ war, aristocracy of Central Europe wished to be buried in the hallowed graveyard at this site. As the number of burials outgrew available space, remains were exhumed and stored in the chapel, then assembled into artistic presentations.

The ruffled collars beneath the candle-bearing skulls are hip bones! At the tip-top are inverted sacra (pl.). Dangling bones are humeri (pl.). Quite the room-lighter! Makes Master Raymond’s animal skulls seem almost quaint!

Image B

Surely, these images put us in the mood to learn more about bones, although this lesson covers bones of the living. Today’s lesson will review and present more bone anatomy and types of bone cells. Then, we will cover events that ensue when bones go snap, crackle, or pop, as well as mechanisms of healing. Let’s go!

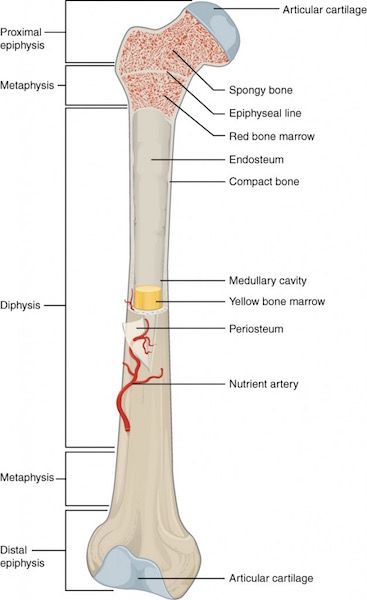

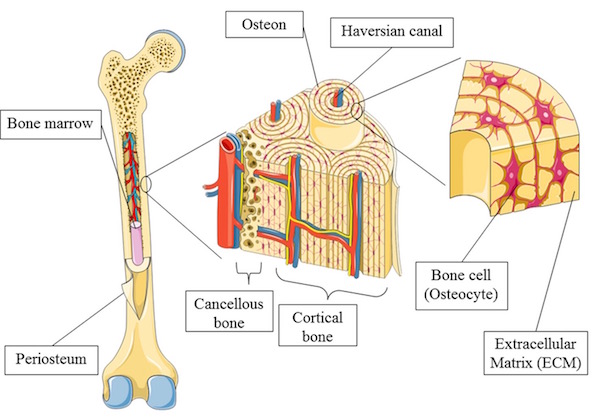

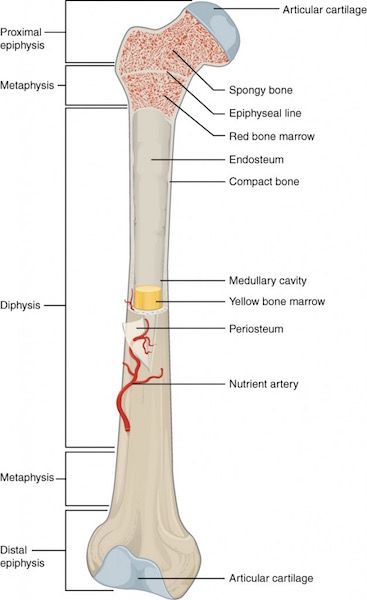

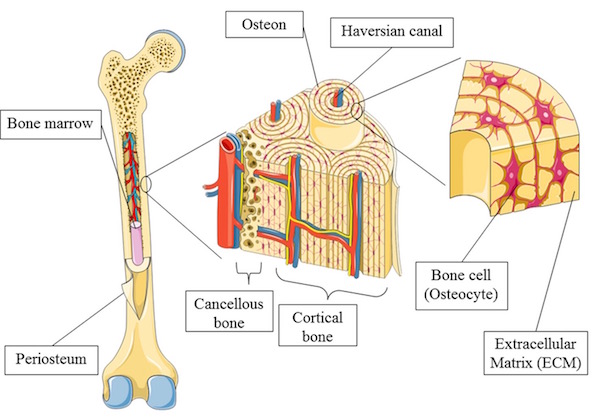

Review of Long Bone Anatomy: Lesson #39 presented long bone anatomy, but let’s take a moment to review. Once again, the femur, is our model (Image C). The shaft of a long bone is the diaphysis. The ends that form joints with other bones are the epiphyses (pl.); these are covered with articular cartilage (ball-shaped epiphysis is head of femur). The flared region between diaphysis and epiphysis is the metaphysis. Cortical bone forms a hard outer rind enclosing the marrow (medullary) cavity. Spongy bone fills epiphyses and metaphyses and is also scattered in the marrow cavity. Depending on the bone and age of the individual, the marrow cavity is filled with either fat cells or hematopoietic (blood-forming) cells, neither of which are elements of bone. Think of them as tenants not owners!

Image C

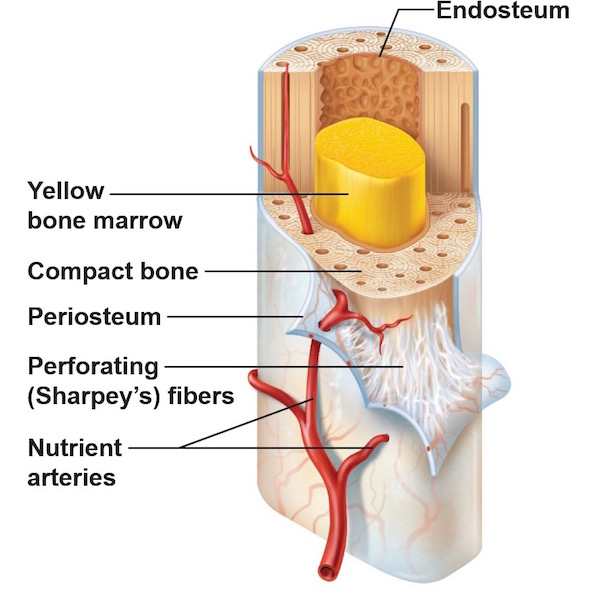

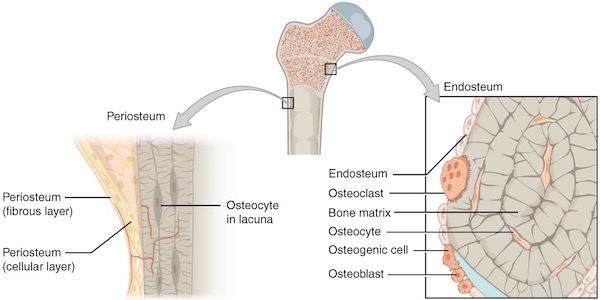

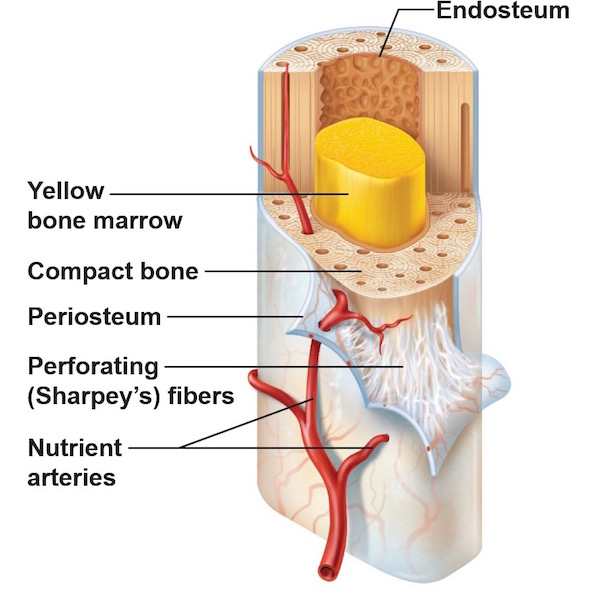

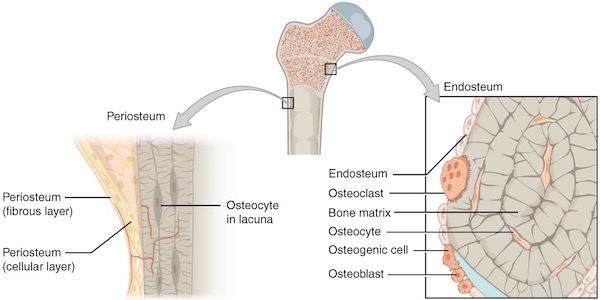

Periosteum and Endosteum: Periosteum is a thick fibrous layer covering the diaphyseal surface (Image D). Endosteum is a thin connective tissue layer lining the bone marrow cavity and covering all exposed surfaces of spongy bone. Both layers contain blood vessels and several types of bone cells as discussed below.

Image D

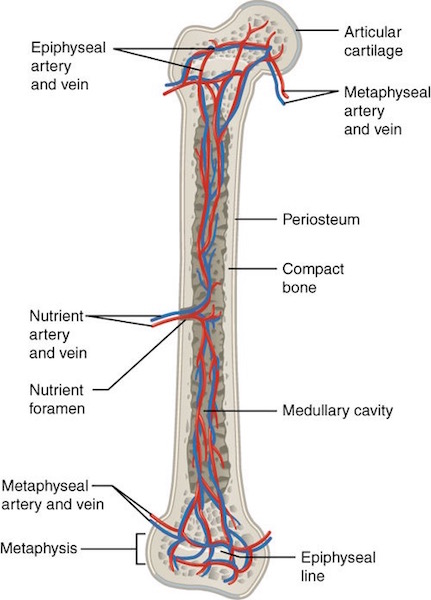

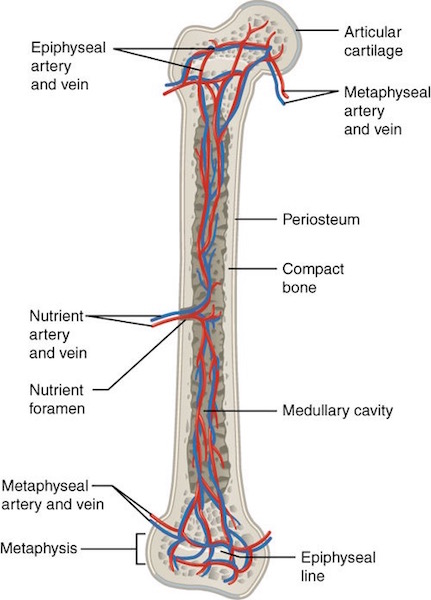

Vascular Supply: As we learned in Anatomy Lesson #39 “Dem Bones – The Human Skeleton,” bone is living tissue and thus requires a constant blood supply such that the human skeleton receives 5-10% of the entire cardiac output (amount of blood the heart pumps per minute).

To meet this demand, large bones receive several arteries (Image E). Periosteal arteries supply periosteum and outer compact bone. Epiphyseal arteries supply blood to epiphyses (pl.). Nutrient arteries supply inner cortical bone, endosteum, and help supply epiphyses and metaphyses.

These arteries access a bone via foramina (channels) that traverse compact bone to reach their respective turfs, then break into capillary beds where oxygen and nutrients are exchanged for carbon dioxide and waste products. Corresponding veins form and blood flows back to the heart. Round and round and round it goes…..

Image E

Nerve Supply: You may be surprised to learn that mineralized bone (organic matrix plus inorganic minerals – see Lesson #39) does not have pain receptors. Hum…if this is true, then why does a broken bone hurt so badly? Because periosteum and endosteum as well as articular surfaces are richly supplied with pain receptors (nociceptors). If these structures are compromised as with a fracture, then pain is severe!

Image F nicely illustrates nerve and blood vessel distribution in cortical bone and margin of the marrow cavity. Anatomy typically color codes arteries red, veins blue, and nerves yellow. The tiny yellow lines indicate that nerves follow blood vessels through cortical bone to the endosteum. Although not shown in Image D, nerves also follow periosteal arteries to innervate the periosteum.

Image F

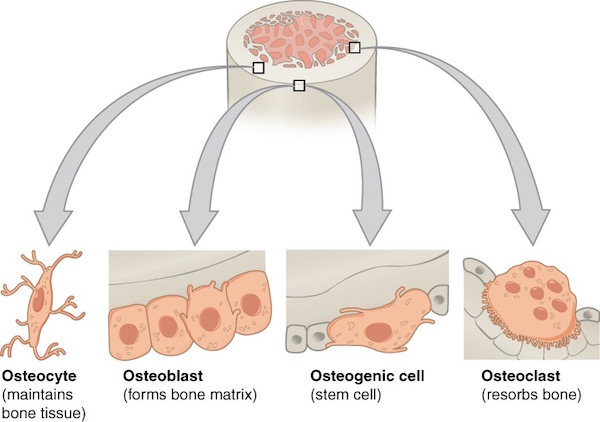

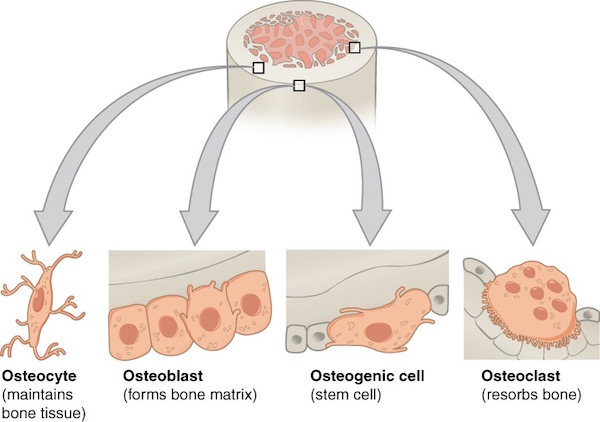

Bone Cells: As mentioned above, bone contains several cell types including osteogenic cells, osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts (Image G). These cells are located in periosteum, endosteum, or within mineralized bone. Again, although hematopoietic cells or fat cells fill spaces between spongy bone and within marrow cavities, these are not bone cells.

Osteogenic cells are stem or parent cells giving rise to osteoblasts (Image G); they reside in periosteum and endosteum.

Osteoblasts: From Greek osteo- meaning bone + blastanō meaning to germinate, osteoblasts produce collagen and other proteins as part of the organic matrix. These proteins are released into the extra-cellular environment where minerals deposit around them. Together, the organic matrix provides tensile strength and inorganic minerals provide compressive strength. As to their bulk, organic proteins represent 10% of bone mass with the remaining 90% being inorganic mineral. Osteoblasts reside in periosteum and endosteum.

Osteocytes: In the course of production and secretion of organic matrix and its subsequent mineralization, osteoblasts become “imprisoned” within bone and are renamed osteocytes. Located in compact and spongy bone, osteocytes help maintain the mineralized bone. Further, the mineralized matrix with imprisoned osteocytes is organized into cylinders of bone known as osteons (Haversian systems). A bone such as the femur contains millions of osteons but details about these units must await a future lesson.

Osteoclasts: Giant, multi-nucleated cells, the osteoclasts, are formed by the fusion of macrophages (Anatomy Lesson # 37, “Outlander Owies Part 3 – Mars and Scars”). Found in endosteum, their duty is to dissolve bone.

Image G

As you might imagine, a good deal of coordination among the various bone cells is required to ensure homeostasis (balance) between bone production, maintenance, and resorption. For example, as a bone grows in circumference due to periosteal osteoblast activity, osteoclasts of the endosteum remove bone from the inside so the thickness remains fairly constant, a highly regulated process.

Image H shows in detail the distribution of bone cells in periosteum, endosteum and in compact bone.

Image H

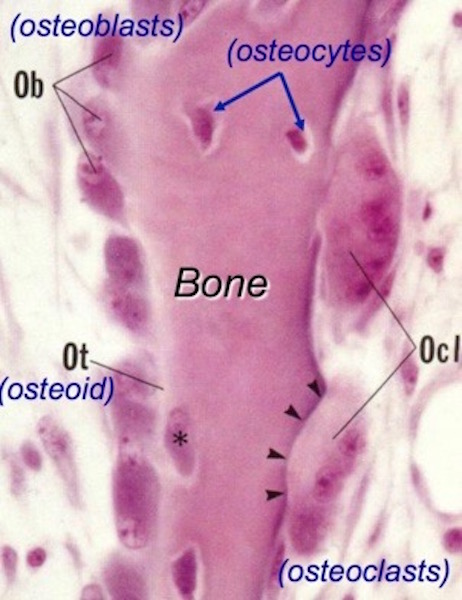

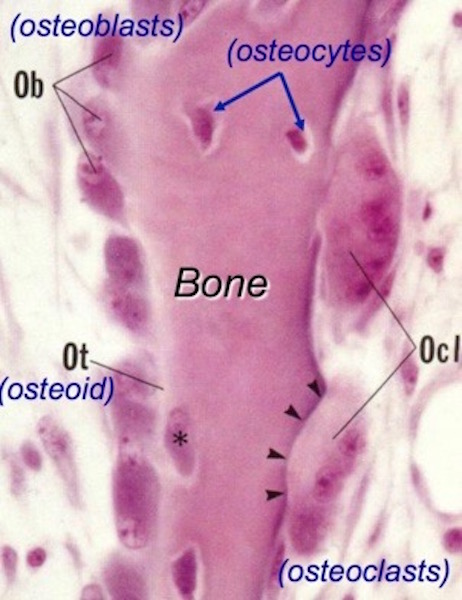

Next, let’s do something really daring and look at a microscopic image of bone cells as viewed through a light microscope (Anatomy Lesson #34 – “The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy”). Please understand that microscopic anatomy, better known as histology (Greek histo- meaning “tissue” + ology meaning “to know”), is a challenge for most students. Watch this fun video by Harvard medical students as they lament about studying “histo!”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BEYogsIuTPz/

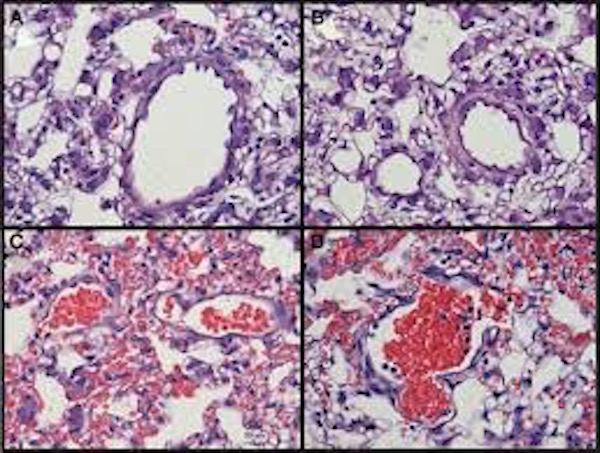

Ha ha! Very clever, medical students! But, you readers might respond the same way looking at a magnified image of a shard of spongy bone (Image I). This image is of a very thin slice of bone that has been stained blue and pink with H&E (hematoxylin = blue + eosin = pink). The so-called H&E stain is the most commonly-used histo stain in the US.

So, what do we see in Image I? The dense pink vertical band is a spicule of ossified spongy bone. The oval cells with pale nuclei along the left border of the shard are osteoblasts laying down a pale layer of unmineralized organic matrix (osteoid). The right border of the spicule show two large multi-nucleated osteoclasts busily dissolving bone – one such interface is a distinct divot indicated by the black arrowheads. Such divots are termed Howship’s lacunae (named for John Howship, a British anatomist). Several irregularly-shaped nuclei are scattered within the bony spicule – these are osteocytes encased in ossified bone.

That’s pretty much it! Being competent at recognizing cells and extracellular substance is based on pattern recognition. Looking at many examples of a given tissue is very useful in obtaining said competence. If you think this is impossible, understand that anatomical pathologists make their living looking at and diagnosing diseases from thousands of such tissue slides.

Image I

Bone Fractures: Time for snap, crackle, and pop, and I dinna mean Rice Krispies! Compressive strength from mineral deposition and tensile strength from organic matrix give normal bones the ability to behave elastically. If trauma overcomes this elasticity, then bones fracture!

Bone fractures fall into two major categories: mechanical bone fractures caused by high force impact or stress, and pathological fractures caused by disease.

Pathological Fractures: Diana presents a fabulous case of fracture caused by disease in Colum. The Laird of clan MacKenzie is haunted by the aftermath of a pathologic fracture and accompanying deformities due to Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome (Starz episode 208, The Fox’s Lair).

Outlander book informs readers that at 18 y.o., Colum took a bad fall breaking the long bone (femur) of his thigh that subsequently mended poorly. Other skeletal anomalies quickly ensued. Diana explains in Dragonfly in Amber:

Legs crippled and twisted by a deforming disease, Colum no longer led his clan into battle…

…He glanced dispassionately down at the bowed and twisted legs. In a hundred years’ time, they would call this disease after its most famous sufferer—the Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome.

Read Anatomy Lesson #27, “Colum’s Legs and Other Things too!” for details about this rare syndrome (1.7 per million births). Of course, there are also many other diseases leading to pathological fractures. Nowadays, the most common in the US is osteoporosis.

Mechanical fractures: High force impact or stress cause bones to snap. Different types of bones (e.g. short vs. long) often exhibit characteristic fractures. This lesson will consider fractures of long bones using the femur again as our example. Fractures are generalized into six different categories:

- Closed fracture – bone is broken but overlying skin is unbroken

- Open fracture – better known as a compound fracture, broken bone pierces the skin

- Simple fracture – bone is broken but no other tissues damaged

- Complex fracture – sharp fracture edges damage surrounding soft tissues

- Complete fracture – bone breaks completely across the shaft

- Incomplete fracture – bone is partly broken but remains in one piece

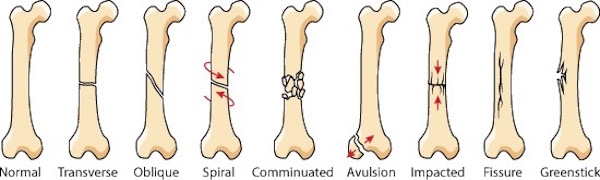

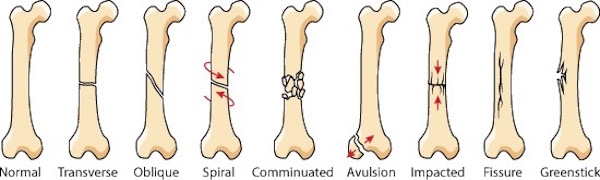

Then, fractures are named according to features of the break (Image J).

- Normal – left image is the normal femur

- Transverse – break crosses the shaft horizontally

- Oblique – break crosses shaft at an angle

- Spiral – torque on the broken halves twists these in opposite directions

- Comminuated – bone is broken into four or more pieces (including main body of the bone)

- Avulsion – a piece of bone is torn away usually by pull of a muscle tendon

- Impacted – bone parts are driven together, also known as a buckle, or compression fracture

- Fissure – crack along one side of the shaft

- Greenstick – incomplete break through the shaft. Analogous to breaking a stick of green wood.

Image J

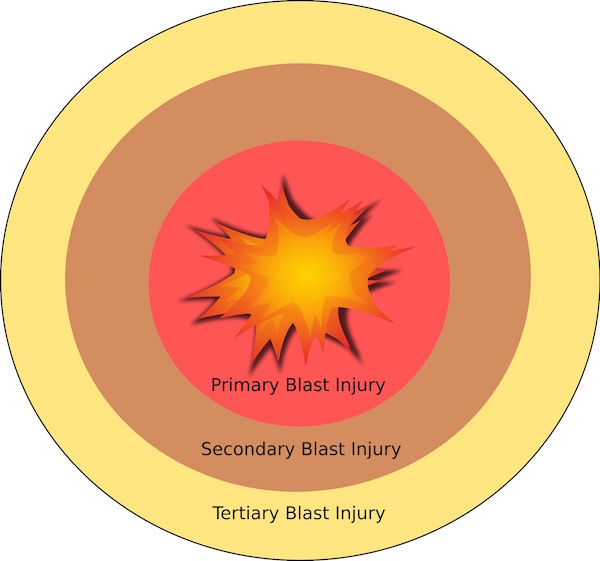

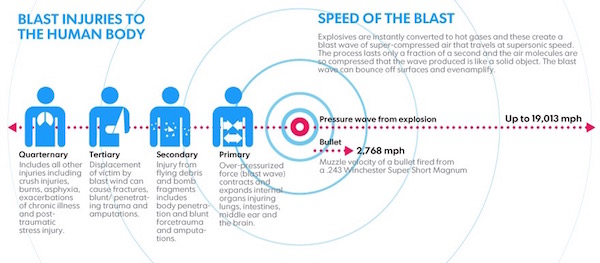

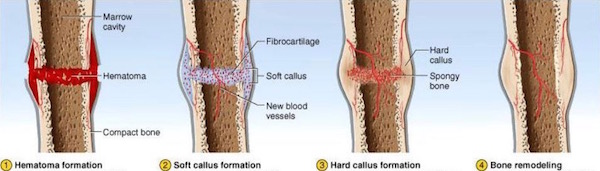

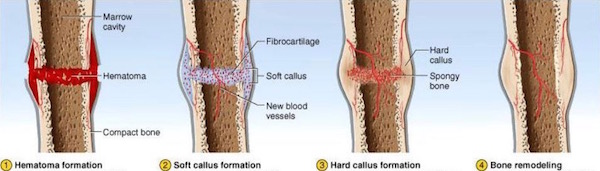

Fracture Healing: Fracture healing is the process by which the body repairs a broken bone and what a process it is! Several overlapping steps occur, different descriptors are used, and times may vary depending on the bone, but the general sequence is (Image K):

- Hematoma Formation (days 1-5): Bone fractures tear blood vessels, and periosteum and endosteum. Blood pours from the damaged vessels forming a hematoma (blood clot) between the fractured surfaces. Blood flow in intact vessels increases such that an army of white cells are delivered for defense and repair.

- Soft Callus Formation (days 3-40): Gradually, a bridge of cartilage and collagen replaces the hematoma and unites the broken ends. The cartilage bridge is made by chondroblasts (cartilage-generating cells) and is termed a soft callus.

- Hard Callus Formation (days 30-80): During this stage, cartilage of the soft callus is gradually replaced with new, woven bone (cartilage does not change into bone) and the site is renamed a hard callus. But, woven bone is immature and not as strong as mature compact bone. Mild exercise is often resumed during this phase.

- Bone Remodeling (days 80-100): If all goes well, the hard callus is gradually replaced with normal, mineralized compact bone that remodels to align with muscle pull and mechanical stress. Exercise promotes this process which is typically 80% complete within three months. But, depending on the bone and the fracture, step four can take up to 18 months.

Image K

Normal fracture healing requires the following:

- Adequate blood supply: Oxygen and nutrients must be delivered to the repair site and carbon dioxide and waste products removed; these processes require blood vessels. Thus, re-vascularization occurs at the fracture site.

- Fracture stabilization: Excessive movement of the fractured bones interrupts callus formation so fractures are immobilized with a variety of ingenious devices such as casts, rods, plates, screws, and external fixators.

- Adequate nutrition: On average, a fracture heals by 12 weeks. However, healing times depend on which bones are broken, severity of the breaks, age (younger folks usually heal faster), and nutrition. A vitamin sandwich (Image L) looks funny but animal and human studies show that fracture healing improves with supplements of Vitamins C, D, and E, as well as calcium and amino acids. Details of these experiments exceed our lesson goals, but understand that many average diets are marginal in these substances. So, be sure to consult with your physician about supplements while healing a bone fracture.

- Rehabilitation: Immobilization of a fracture contributes to muscle wasting. Physical therapy can provide critical support in re-building muscle and encouraging proper bone alignment. This includes weight-bearing on a fracture after it has mostly healed in order to build bone strength.

- No-No nicotine: Studies are pretty clear that nicotine in any form hinders the process of bone healing. Avoidance behavior!

Image L

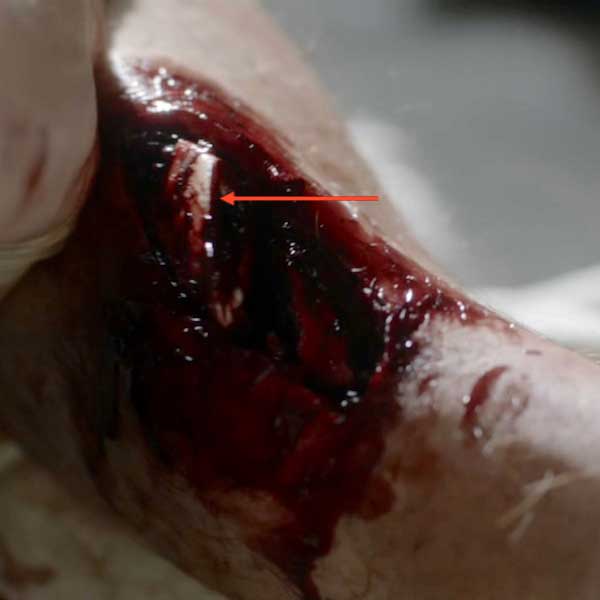

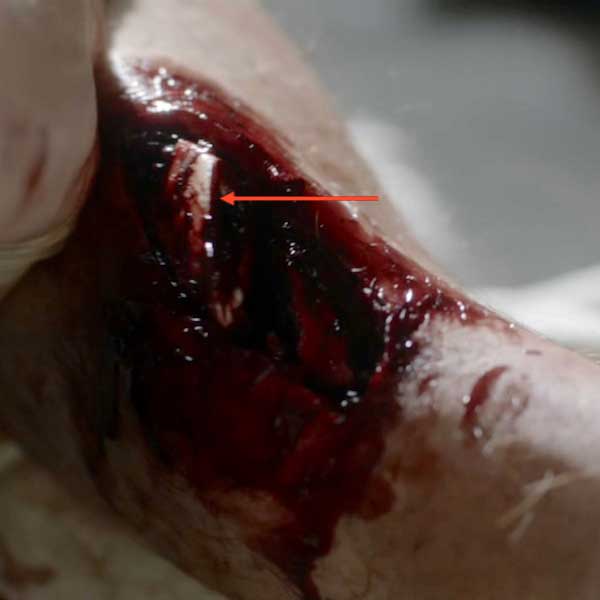

Now for some real “fun.” With Starz images, let’s use applied anatomy to consider mechanical bone fractures and healing. Starz Outlander episodes offer two excellent examples of bone fractures, both are compound in type.

A workman is admitted to L’Hôpital des Anges in Paris (Starz episode 204, La Dame Blanche). He screams in agony because he has suffered a compound fracture of the right tibia (Anatomy Lesson #27, “Colum’s Legs and Other Things too!”). The skin is open and the upper part of the broken tibia is clearly visible at the red arrow.

This injury hurts like holy toothpicks because tears of periosteum and endosteum stimulate nociceptors (pain receptors). Then, muscles spasm as they attempt to stabilize bony fragments, upping the pain meter. And, adding insult to injury, a compound fracture rents the skin and we all ken how sensitive skin is to pain! All around, an agonizing situation.

So, what does a good hangman do to ease his patient’s discomfort? Why, he hammers a nail into the side of the poor fellow’s knee, of course! What else? Presumably a type of primitive acupuncture, it momentarily halts the patient’s agony; mayhap from PTSD?

A quote from Dragonfly in Amber:

Monsieur Forez was at work today. The patient, a young workman, lay white-faced and gasping on a pallet. …The leg, though, was something else… Sharp bone fragments protruded through the skin … “Here, ma soeur ,” he directed, taking hold of the patient’s ankle. “Grasp it tightly just behind the heel… Monsieur Forez brought the point of the brass pin to bear …he drove the pin straight into the leg with one blow. The leg twitched violently, then seemed to relax into limpness.

Monsieur Forez enlightens Claire regarding this startling exhibit of bedside manner (from Dragonfly in Amber):

“There is a large bundle of nerve endings there, Sister, what I have heard the anatomists call a plexus. If you are fortunate enough to pierce it directly, it numbs a great deal of the sensations in the lower extremity.”

Stop! I must pick at a wee bone: During the episode, Mr. Forez explains to Claire that anatomists describe a nerve at the inside of the knee which, if pierced, briefly anesthetizes the leg (Anatomy Lesson #27 – “Colum’s Legs and Other Things too!”). So, the human grease-guy whacks a 4” nail into the side of the workman’s knee for pain relief!

So this is what troubles me: the nail pierces skin near the saphenous nerve (a branch of the femoral) which, unfortunately, supplies only skin of the area and does nothing for bone pain. The correct nerve to pierce would be the tibial nerve, a branch of the sciatic; but, both of these nerves are in the back of the thigh! From the thigh, the tibial nerve sends fibers to the tibia in concert with its nutrient artery where it innervates endosteum and periosteum. Ergo, for this technique to work, the good Monsieur must pierce the tibial nerve in the back of the thigh.

I canna vouch for the efficacy of nail piercing, which seems a wee bit harsh, but I can question Forez’s anatomists and their data base. Soon after the shock of piercing subsides, the patient resumes screaming so I canna think it verra efficacious. Gah! Back to the dissection lab for those anatomists! But, I must say, the special effects are superb!

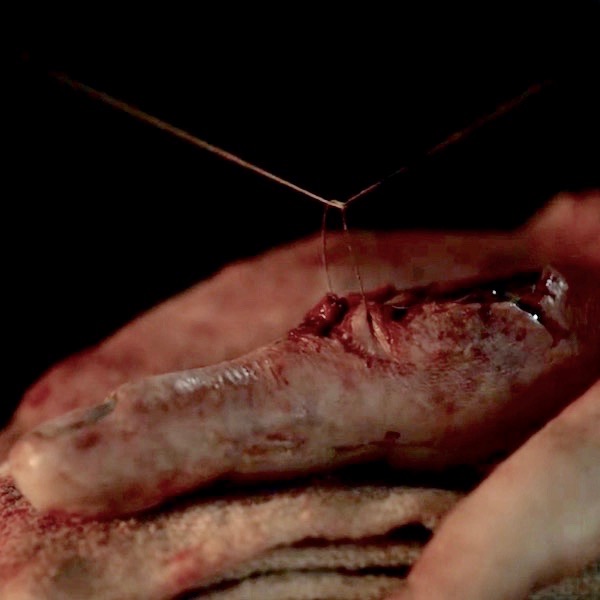

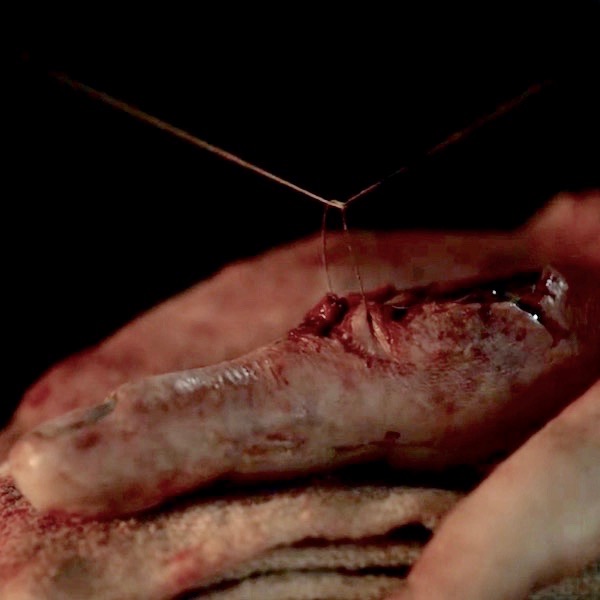

Next, we will consider another compound fracture, arguably the most infamous of the Starz series. The Wentworth Smack-Down delivered high force impact causing mechanical fractures of Jamie’s left hand bones (Starz episode 115, Wentworth Prison). Let’s do a walk through of these fractures.

Heading to Outlander book, Diana enlightens us with these quotes:

Luckily the thumb had suffered least; only a simple fracture of the first joint. That would heal clean. The second knuckle on the fourth finger was completely gone; I felt only a pulpy grating of bone chips when I rolled it gently between my own thumb and forefinger…

The compound fracture of the middle finger was the worst to contemplate. The finger would have to be pulled straight, drawing the protruding bone back through the torn flesh. I had seen this done before—under general anesthesia, with the guidance of X rays.

We can easily deduce from Diana’s description that, at a minimum, Jamie’s hand suffered:

- Simple fracture of the first phalanx of thumb.

- Communiated fracture of the ring finger (4th finger in English system; 3rd in US system – see Anatomy Lesson #22, “Jamie’s Hand – Symbol of Sacrifice”) – proximal and middle phalanges smashed into bony bits.

- Compound fracture of middle finger – appears to be middle phalanx of the middle finger.

Like any combat nurse worth her salt, Claire cleanses Jamie’s wounds. She has no modern isotonic fluids or antibiotics, so she cleans his compound fracture with (no doubt) sterile water, perhaps containing a wee dram of alcohol for sterilization?

Next, Claire ponders the damage and then re-aligns and resets the bony fragments (Starz episode 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul). And again from Outlander book:

I began to lose myself in the concentration of the job… deciding how best to draw the smashed bones back into alignment.

Now, as we learned above, a compound fracture tears surrounding flesh and skin. So Claire carefully closes the wounds with sutures (Starz S.2, introductory image) to exclude pathogens and reduce blood loss.

Earlier in this lesson, we read that movement of a new fracture interferes with callus formation. So, various devices are used to immobilize fractures as they heal.

Ever resourceful Claire (or the monks?) devises an external fixator for Jamie’s smashed hand in the form if a very clever wire/leather, linen, and wood device! External fixation is a surgical treatment used to stabilize bone and soft tissues at a distance from the injury. So, check out the amazing invention (Starz episode 116, To Ransom A Man’s Soul) to immobilize Jamie’s hand! The middle finger is reset and stitched. The communiated and most severely wounded ring finger is stitched and splinted against the small finger. Brava, Madam Sassenach!

Jamie’s hand care is not yet complete! Claire provides physical therapy in the form a rag ball she made. Squeezing the ball helps Jamie regain hand mobility and strengthen the knitting bones as he and Murtagh plan how best to skewer BJR (Starz episode 203, Useful Occupations and Deceptions)!

In case you forgot from earlier in this lesson, exercising a repairing bony callus augments the ossification process, so Claire’s rehabilitation plan is spot on!

Two quotes from Diana’s Dragonfly in Amber:

It really wasn’t too bad; a couple of fingers set slightly askew, a thick scar down the length of the middle finger. The only major damage had been to the fourth finger, which stuck out stiffly, its second joint so badly crushed that the healing had fused two finger bones together. The hand had been broken in Wentworth Prison, less than four months ago, by Jack Randall.

He had regained an astounding degree of movement, I thought. He still carried the soft ball of rags I had made for him, squeezing it unobtrusively hundreds of times a day as he went about his business. And if the knitting bones hurt him, he never complained.

And, pithy quotes from Diana’s Dragonfly in Amber remind us that months later, Jamie’s hand is still not whole (Starz Season 2 opening images), so clever caring Claire applies her personal version of massage therapy… a task that she and he undoubtedly relish! Hee, hee.

I crawled in beside him and took up his right hand, resuming my slow massage of his fingers and palm. He gave a long sigh, almost a groan, as I rubbed a thumb in firm circles over the pads at the base of his fingers.

Thus ends Outlander compound fractures and healing. Whether bone breaks or skeletons, people are endlessly fascinated by bones and the stories they tell. Book readers will recognize this poignant commentary from Dragonfly in Amber as Jamie and Claire find the bony inhabitants of an unknown cave in France.

He turned again then to the two skeletons, entwined at our feet. He crouched over them, tracing the line of the bones with a gentle finger, careful not to touch the ivory surface. “See how they lie,” he said. “They didna fall here, and no one laid out their bodies. They lay down themselves.” His hand glided above the long arm bones of the larger skeleton, a dark shadow fluttering like a large moth as it crossed the jackstraw pile of ribs.

Now, I have my own bone story to share. The following is a true event underscoring the amazing capacity of bones to heal. During WW II, my father was a welder of Liberty Ships in California. When I was 18 months of age, neighborhood kids accidentally ran over me and the trauma snapped off the head (ball-shaped epiphysis) of my right femur. Local physicians were unable to help so they sent us to the Treasure Island Naval Base where many of the best US physicians were stationed to assist with the war effort.

Those docs had never set a child’s femoral head before, but they courageously reset my leg, placed me in a 3/4 body cast, and prepared my parents for the bad news: the blood supply to the femoral head was likely severed, the femoral head would become necrotic (die), and the hip would freeze into an immobile joint. I would not walk normally, if at all.

Well, the good news is that my femoral head did not perish! Somehow and somewhere, an arterial supply survived. Although my colleagues and I share theories about which vessel might have remained intact, no one knows for sure.

Image M was taken in 1944 at Stinson Beach, CA, six months after the injury (like the artery, my appetite clearly remained intact <G>). Observe that the right leg is slightly rotated outward (externally), a classic stance following a femoral head fracture.

Today, the only residual is my right leg is 3/8” shorter than the left. Otherwise, nada! I am able to exercise vigorously and with no noticeable deficit. Blessings to those unknown healers who helped the wee bairn of a common laborer!

Image M

Our lesson on how fractures heal has come to an end. After two lessons about the skeleton, there remains much more to be studied, so we may revisit this topic at a later date.

A few last thoughts: Remember, bone is a dynamic tissue which constantly remodels itself throughout life. Individual bones are organs that collectively constitute the skeleton, our internal support system. Bone cells create, maintain, and destroy bone tissue to our benefit.

Bones have been prodded, examined, healed, revered, saved, feared, embellished, and cherished. Not all of this lesson is about happy stuff, so let’s end with this slightly irreverent image from the bow of the Titanic.

Image N

Dem bones, dem bones!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist.

Photo creds: Starz, Outlander Anatomy archives (Image M), www.anatomy-medicine.com (Image F), www.askabiologist.edu (Image J), www.apps.carleton.edu (Image B) www.boneandspine.com (Image C), www.geneticliteracyproject.org (Image L), www.medcell.med.yale.edu (Image I), www.reddit.com (Image A), www.en.wikipedia.org (Image E; Image H), www.everythingfunny.org (Image N), www.commons.wikimedia.org (Image G) ,www.studyblue.com (Image D), www.ippe2ools.blogspot.com (Image K)