Greetings, anatomy students! Several of you have asked for an exploration of the “skeleton scene” shown in Outlander episode 305, Whiskey and Freedom. Although Anatomy Lesson #39, Dem Bones – Human Skeleton, examined the entire human skeleton, this lesson focuses on skeletal analysis performed by Dr. Abernathy with input from Dr. Claire.

The “skeleton scene” is a great adaptation of Chapter 20, “Diagnosis,” from Voyager book, by Diana Gabaldon. So, put on your forensic cap and let’s begin with a summary of that scene.

Here, the anthropology office at Harvard seeks Dr. Abernathy’s expertise to determine cause of death using skeletal remains. In the book, the skeleton arrives at his office in a box labelled “PICT-SWEET CORN.” I remember that brand!

In the episode, bones are laid out on a desk top (Image A). From Voyager:

Horace Thompson was probably someone from the coroner’s office, I thought. Sometimes they brought bodies to Joe that had been found in the countryside, badly deteriorated, for an expert opinion as to the cause of death. This one looked considerably deteriorated.“

…from the anthropology department at Harvard,” he said… “asked me would I have a look at this skeleton, to tell them what I could about it.”

Image A

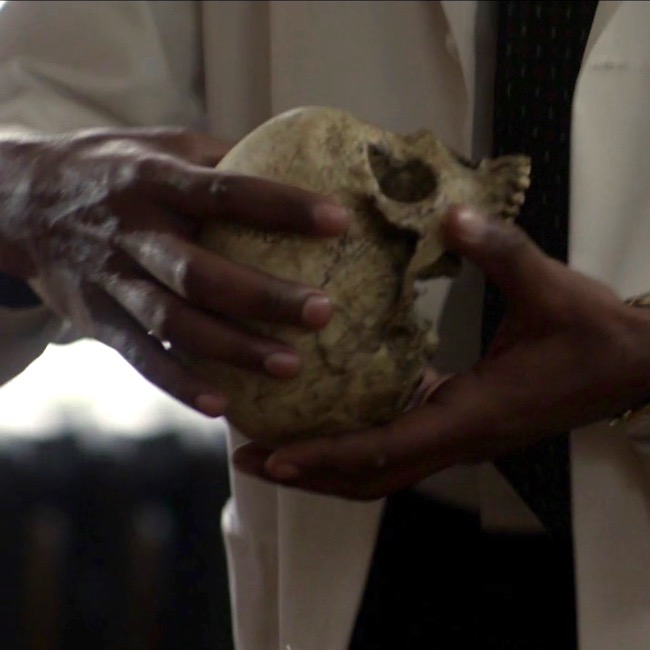

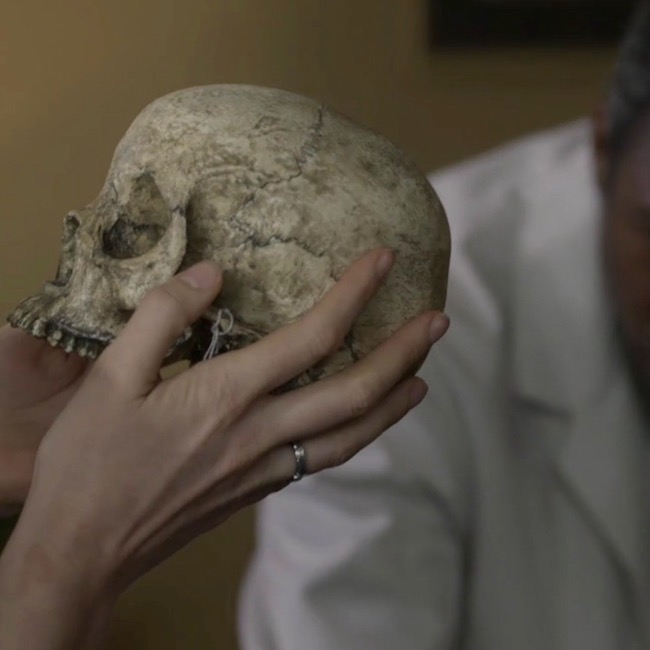

Dr. Abernathy reaches into the box and removes the skull (Image B).

Image B

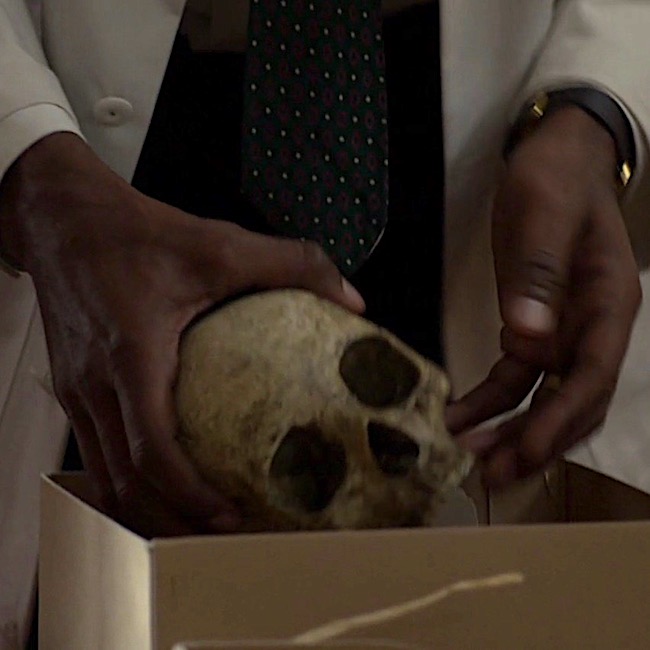

Examining the skull, the good doctor concludes it belonged to a pretty lady who was mature and middle-aged (Image C). And, from Voyager:

As the saying goes, “Pretty is as pretty does.” The owner of this skull definitely did not do pretty things! 😳

“Oh, pretty,” he said in delight, turning the object gently to and fro. “Pretty” was not the first adjective that struck me; the skull was stained and greatly discolored, the bone gone a deep streaky brown. Joe carried it to the window and held it in the light, his thumbs gently stroking the small bony ridges over the eye sockets. “Pretty lady,” he said softly, … “Full-grown, mature. Maybe late forties, middle fifties.”

Image C

Clairvoyant Claire picks up the skull, which speaks to her (Image D). Well, not really – that would be weird – though Hallowe’en does draw nigh! Another quote from Voyager:

Then I held it close against my stomach, eyes closed, and felt the shifting sadness, filling the cavity of the skull like running water. And an odd faint sense—of surprise?

“Someone killed her,” I said. “She didn’t want to die.”

Image D

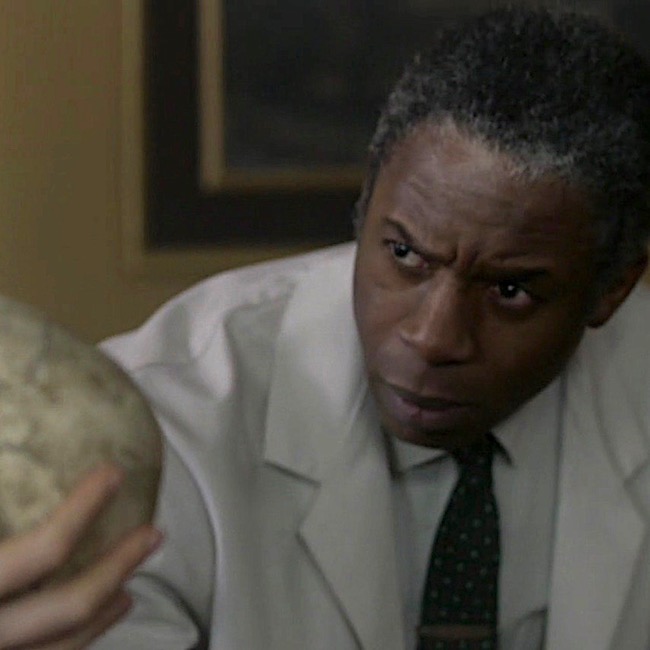

Dr. Abernathy fixes Dr. Claire with a gimlet eye. Lady Jane, have you lost your scalpels??? After all, how could she possibly conjure such details using a touchy-feely method of scientific inquiry? Well, the lass does harbor some awesome powers that seem to grow with time (Image E)? Again, from Voyager:

… “Where did you find her?” I asked….

“She’s from a cave in the Caribbean,” he said. “There were a lot of artifacts with her. We think she’s maybe between a hundred-fifty and two hundred years old.”

Image E

Next, Dr. Abernathy plucks two pieces of bone from the corny box (Image F). “You were right,” he says. Looking at them, he observes that the fracture plane runs through the centrum, although he doesn’t identify which bone has been fractured.

Voyager book reveals the fractured bone as a vertebra (bone of spine) – more specifically, it is the axis, aka the second cervical vertebra (C2).

The wide body of the axis had a deep gouge; the posterior zygapophysis had broken clean off, and the fracture plane went completely through the centrum of the bone.

Joe’s finger moved over the line of the fracture plane. “See here? The bone’s not just cracked, it’s gone right there. Somebody tried to cut this lady’s head clean off. With a dull blade,” he concluded with relish.

Image F

Then, Dr. Abernathy notes that although the burial site was a cave filled with slave artifacts, this lady was not a slave! He points to two leg bones (Image G), the tibia (Anatomy Lesson #9, The Gathering or Boar Gore) and the femur (Anatomy Lesson #7, Jamie’s Thighs or Ode to Joy!). Ahhh, Claire sagely nods, “the crural index.” Back to Voyager, again:

“Not a slave,” he said… “No,” Joe said flatly. He tapped the long femur, where it rested on his desk. His fingernail clicked on the dry bone. “She wasn’t black.”

“Take a look at this,” Joe invited. “You can see the differences in a lot of bones, but especially in the leg bones. Blacks have a completely different femur-to-tibia ratio than whites do. And that lady”—he pointed to the skeleton on his desk—“ was white. Caucasian. No question about it.”

…“If you want to think blacks and whites are equal under the skin, be my guest, but it ain’t scientifically so.” He turned and pulled a book from the shelf behind him. Tables of Skeletal Variance, the title read.

Image G

OK, that pretty much summarizes the salient scientific points of this scene, although I see three issues that warrant comment:

-

-

- Can bones reveal sex, age and/or beauty of the owner?

- Does the fractured bone match with “pretty lady’s” death?

- Can crural index determine race?

-

Issue #1: Can bones reveal sex, beauty and/or age of the owner?

The answer is a qualified yes.

When Claire arrives at the office, Dr. Abernathy has already laid out most of the skeleton and presumably, has already examined each of these bones. It’s pretty iffy to hazard a reliable guess with one measurement. But, if a series of measurements tend to fall within a given range, a forensic scientist can venture an educated guess. So, assuming he examined the skull and pelvis, then sex can be surmised with a resonable degree of confidence. Here’s why.

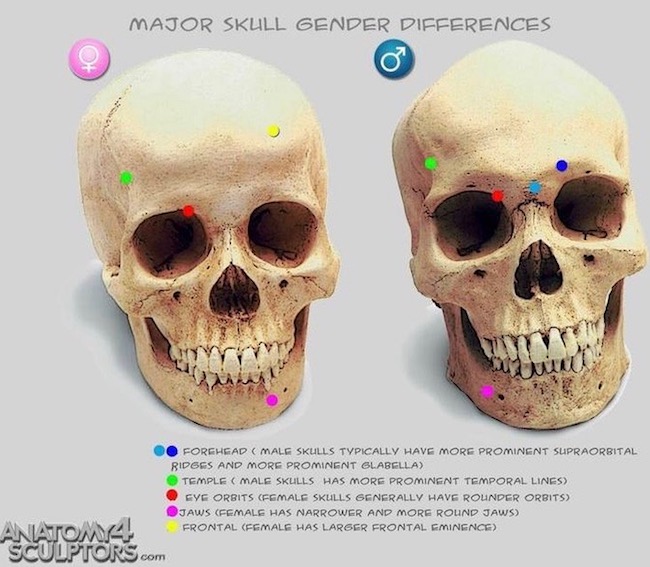

Sex & Skull: “Typical” female and male skulls exhibit differences (Image H). A female skull is usually smaller, with rounder orbits (red dot), prominent frontal eminences (yellow dot), smaller mandible (pink dot), less prominent temporal lines (green dot), smaller brow ridges (dark blue dot), and less pronounced glabella (turquoise dot), and the brow ridges are sharper. There are also other, more subtle differences, but understand that not all skulls show all structural differences, regardless of genetic sex.

Image H

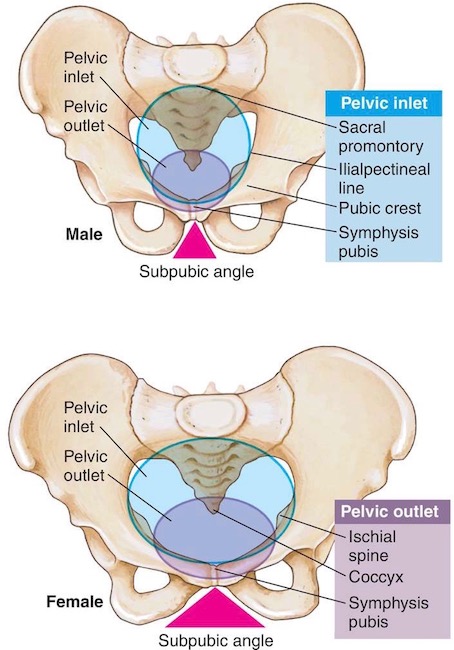

Sex & Pelvis: The bony pelvis also supplies important clues to sex. “Pretty lady’s” bony pelvis lies in three pieces (two hip bones plus sacrum). The pelvic width, shape of sacrum, sub-pubic angle and shape of obturator foramen (two front holes) are consistent with a female pelvis (Image I – obturator foramen not labeled). Pelvic inlet and outlet are difficult to demonstrate in a dissembled bony pelvis but, assembled they would be similar to those shown in Image I, lower figure. Ergo, pretty lady’s pelvic features are consistent with those of a female.

Age: Age can be estimated if cranial sutures (sites where cranial bones meet) are thin, bony ends are fused to bone shafts (growth plates are ossified), teeth are mature and bones are hard, along with the presence of wear-and-tear diseases, etc. So, yes, with careful analysis, general age can be estmated. Presumably, Dr. Abernathy considered these before Claire’s arrival. So far, so good!

Beauty: As we all ken, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Dr. Abernathy expresses an opinion when he dubs the owner a “pretty lady.” Of course, he cannot know how flesh draped those bones, but he considers the skull to be delicate and beautiful to his practiced eye. This is a subjective response on his part, but it is arguably consistent with the appearance of the skull which is delicate with good teeth. Nowadays, forensic scientists can reconstruct a face using computer programs, or the older clay sculpting technique.

Thus, sex and age can be assessed with a fair degree of confidence if and only if multiple measurements and observations are considered, collectively. But, as beauty remains in the eye of the beholder, this issue receives a qualified yes.

Image I

Issue #2: Does the fractured bone match with “pretty lady’s” death?

Because I have some issues with this issue, the answer is mostly yes for the book, but no for the episode. Here’s why. 🤓

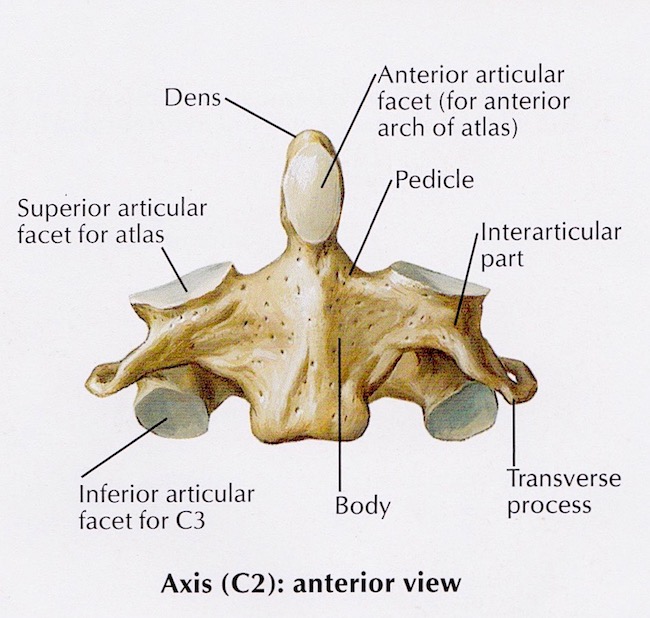

Dr. Abernathy holds up a wee bone, which is broken vertically into two nearly symmetrical pieces. Voyager identifies these fragments as belonging to the axis. The axis is one of seven neck bones (numbered 1-7 from skull downwards); it is also designated as C2, meaning it is second of the seven cervical vertebrae. The purpose of cervical vertebrae is to support the head and supply flexibility to the neck, augmenting movements of the head and shoulders.

Voyager book states:

The wide body of the axis had a deep gouge; the posterior zygapophysis had broken clean off, and the fracture plane went completely through the centrum of the bone.

Although the bone fragments of shown in episode 305 are supposed to represent a vertebra, the fragments do not appear to be an axis. The axis is an atypical, weird-looking bone (Image J – gif):

Image J

However, please appreciate that the axis is a splendid bone, allowing us to rotate our head from side-to-side in a “no-no” gesture (Anatomy Lesson #12 Claire’s Neck – the Ivory Tower!).

Try this: Cervical vertebrae are buried rather deeply in the neck and difficult to demonstrate. But, if you able, sit up straight with chin level, place a finger in the groove of your neck just below the skull. You may feel a small bulge under your fingers. This is the spine of the axis.

Let’s examine the parts of the axis (Image K – front view) to help us understand the quote from Voyager.

- The axis has a robust body, located at its front surface.

- Inside the body is a centrum, a remnant of embryonic development. You cannot see the centrum from the surface.

- Dens is a tooth-like structure perched atop the body.

- Superior articular facets (aka superior zygapophyseal processes) are flat surfaces where C2 forms joints with C1 above.

- Inferior articular facets (aka inferior zygapophyseal processes) are flat surfaces where C2 forms joints with C3 below.

- Joints are sites where movement occurs between bones – between vertebral facets these are called zygapophyseal joints.

To reiterate, Voyager book states:

The wide body of the axis had a deep gouge; the posterior zygapophysis had broken clean off, and the fracture plane went completely through the centrum of the bone.

Analysis: The book statement is a wee bit awkward because if the fracture plane passed through the centrum, it must necessarily cleave the body, so a deep gouge would not have been left to discern.

Also our vertebrae don’t have posterior zygapophyses – I suspect Diana intended inferior rather than posterior. Assuming this is correct, then: The dull blade cut horizontally (as in cutting off a head), breaking off the inferior zygapophyses (forming zygapophyseal joints with C3), and passing through the axial body and its centrum. Otherwise, the description makes sense.

One may also conclude, the blade must have passed through the lower part of the axis. Had the blade passed through its upper part, the stroke would have sheared off dens and superior zygapophyses but completely missed the centrum! Make sense? Yay! 👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

Image K

Conclusion: Dr. Abernathy holds two bony fragments of the fractured bone and I think, hum… that ring of bone appears to have been cleaved in halves by a vertical blow (Image L)! The only way a vertical fracture could occur is if the blade sliced downward, vertically cleaving the skull and its supporting cervical vertebrae. Gah! I think you will agree, this is pretty unlikely plus, the skull remains intact. So, no vertical swipe of the blade!

Ergo, although dramatic and interesting, the bone fragments do not reflect the axis damage as described in Voyager or by episodic Dr. Abernathy. Now, does all this keep me up at night? Hardly – I loved this scene despite its wee anatomical issues!

Image L

Issue #3: Can crural index determine race?

The answer is a qualified no.

This topic is a super sticky-wicket but very important to consider, so bear with me.

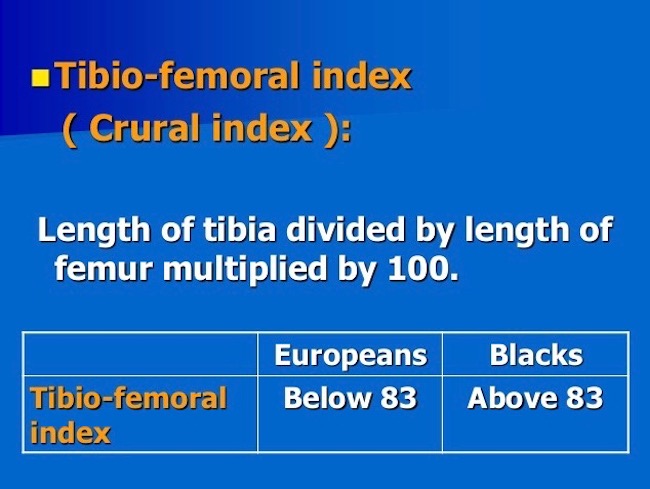

Best start with a definition: the crural index, established in 1933, is the ratio of tibia-to-femur (not femur-to-tibia, as this yields different results). The formula to determine crural index is:

(length of tibia x 100) / length of femur OR

(length of tibia/length of femur) x 100

Using this ratio, many studies showed that individuals of African descent had higher crural indices than those of European descent. Image M is a simplified, summary version of such findings.

In 1968, Dr. Abernathy was positive that a low crural index meant “pretty lady” was white….“No doubt about it.”

(BTW, I am pretty sure Claire pronounces this “cruel index;” but, it should be crural <kru-ral>, from the Latin crus meaning “leg”)

Image M

So, can race be determined from the crural index?

When I started graduate school in 1965, we were taught there were three human races: negroid, caucasoid, mongoloid. Fast forward 52 years and much has changed! Today, many biologists say race cannot be determined from bones because there is no such thing as race. These scientists posit that all living humans belong to one species (Image N): Homo sapiens sapiens (the second sapiens denotes the subspecies – that would be us).

Many designate the term ancestry, because race and even ethnicity have confusing connotations and definitions. Furthermore, they point out, more genetic variations can occur within “racial” groups than between them, meaning findings are limited by the sample studied. What a conundrum!

Just to clarify, some bony physical traits are characteristic of ancestry and can be traced to a particular global location. But, bear in mind, people of mixed ancestry may present features which do not fall neatly into any category. Also, humans are so similar that all bone morphologies are present in all groups, just at varying rates. Despite such variations, skeletal analysis remains part and parcel of human identification especially when numerous skeletal measurements are obtained. Today, using calipers, x-rays, microscopy, DNA, and a mess of other tools, some of which were unavailable in 1968, forensic researchers can make reasoned guesses as to a person’s ancestry based on skeletal remains.

Summary: Nowadays, before a scientist suggests ancestry based on skeletal remains, (s)he makes multiple measurements, never relying on just one. And, prudent scientists avoid stating “we are sure” (even if they are). Instead, they posit, the data suggests or indicates or is consistent with or is likely. Verra prudent!

Hence the qualified “no” regarding the crural index; it is only one skeletal measurement and insufficient to make a judgement if a person was white or a not. However, Voyager accurately expresses views prevalent in the 1960’s. Make sense? Ta da!

Image N

Bottom line:

-

- Today’s competent (my word) scientist cannot/will not declare ancestry using a single skeletal measurement such as crural index. 👎🏻

- Cutting (hah) Dr. Abernathy some slack, his surety about the skeleton’s “race” was suitable and justifiable for his time (1968), but untenable for ours (Image O)!

Image O

So, this concludes a brief analysis of the “skeleton scene.” Much more could be added, but would likely be too technical for most students. Hopefully, this summary was enlightening and will generate some thoughtful discussion and consideration in our ever expanding Outlander world. Buh-bye, pretty lady!

Ode to Pretty Lady

Your bones tell a tale.

Who are you?

Were you well?

Were you pretty?

Were you witty?

Were you sweet?

Did you cheat?

Were you bad?

Were you sad?

Or, were you mad?

Your bones tell a tale.

No Spoilers! Who are you “pretty lady?” Mayhap, we will find out during Outlander S.3!

The deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Follow me on:

-

- Twitter: @OutLandAnatomy

- Facebook: OutlandishAnatomyLessons

- Instagram: @outlanderanatomy

- Tumblr: @outlanderanatomy

- Youtube: Outlander Anatomy

Photo Credits: Sony/Starz (Images A-G, L, O), Clinically Oriented Anatomy by Moore and Dalley, 5th edition (Image K), www.pinterest.com (Image H), www.medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com (Image I), www.premiersourceshopping.com (Image O), www.slideshare.net (Image M), www.wikipedia.com (Image J – gif)