Although discussion of a medicine chest is not a typical anatomical topic, it is not unrelated, so welcome anatomy students! A good deal of interesting stuff is stuffed into this lesson.

In Outlander episode 401, American the Beautiful, Jamie presents his beloved wife with a surprise aboard the barge bound for River Run. In honor of their 24th wedding anniversary (King of Men didna forget!), he gifts Claire with a stunning wooden cabinet.

Claire gapes at the curious structure.

Several quotes from Drums of Autumn (DOA), Diana’s fourth big book, sets the stage for his superb anniversary gift:

“What’s this?” I ran my hand curiously over the box.

“Oh, only a wee present.” He didn’t look at me, but the tips of his ears were pink. “Open it, hm?”

Rollo oversees and approves. Woof! Woof!

Quoting again from DOA, Herself explains:

It was a heavy box, both wide and deep. Carved of a dense, fine-grained dark wood, it bore the marks of heavy use—nicks and dents that had seasoned but not impaired its polished beauty.

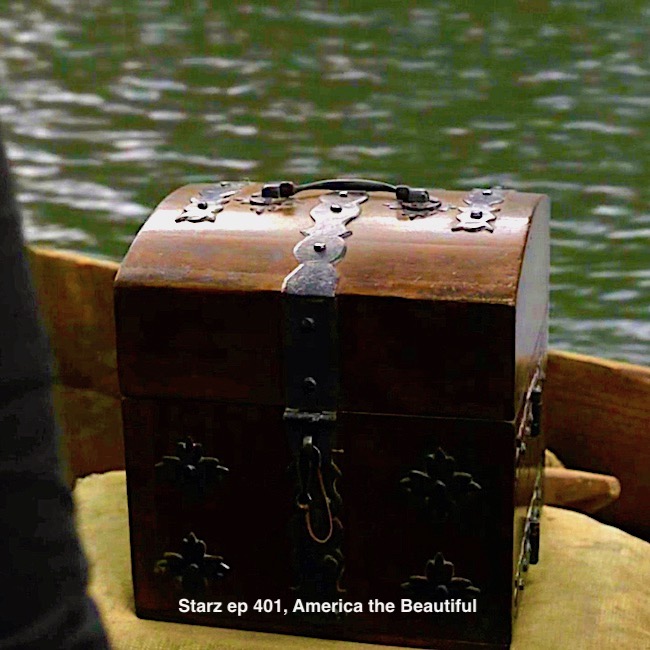

Clearly, the Outlander team got it right with their imagined version of Jamie’s gift. It matches DOA’s medical box description to a “T,” even down to the wear-and-tear of the wooden exterior. Fans will appreciate that the splendid gift was created just for Outlander. Set Decorator, Stuart Bryce, enlightens us (quote from Outlander Community website):

“The medical box was researched extensively. We found references to a type of eighteenth-century, portable chest—a surgeon’s chest. We had three versions made bespoke for the show by a specialist antique company, Wetton and Grosch. It is one hundred percent period accurate. The first version is the ‘master,’ all bells and whistles, but it is prohibitively heavy to work with as a movable prop, either for Caitriona, or even for a horse to carry, so we had two lighter versions built too. Within the wooden chest are lots of little drawers and compartments for all the tinctures and tools and instruments required, from the microscope to cutting instruments, a little mortar and pestle…”

To appreciate the wooden casing of the box created for this episode, Image A shows the exterior of an authentic 18th century medical chest: domed lid, brass fixtures, medallions, hinges and handle. Kudos to the set and props peeps!

Image A

Another quote from DOA:

…the lid rose easily on oiled brass hinges, and a whiff of camphor floated out, vaporous as a jinn. The instruments gleamed under the smoky sun, bright despite a hazing of disuse. Each had its own pocket, carefully fitted and lined in green velvet.

The show version is lined with red velvet and surgical instruments are secured to the lid with metal brackets rather than pockets, but to me, these differences seem of little consequence.

Claire takes a quick inventory of the contents. Continuing the quote from DOA:

A small, heavy-toothed saw; scissors, three scalpels—round-bladed, straight-bladed, scoop-bladed; the silver blade and a tongue depressor, a tenaculum …

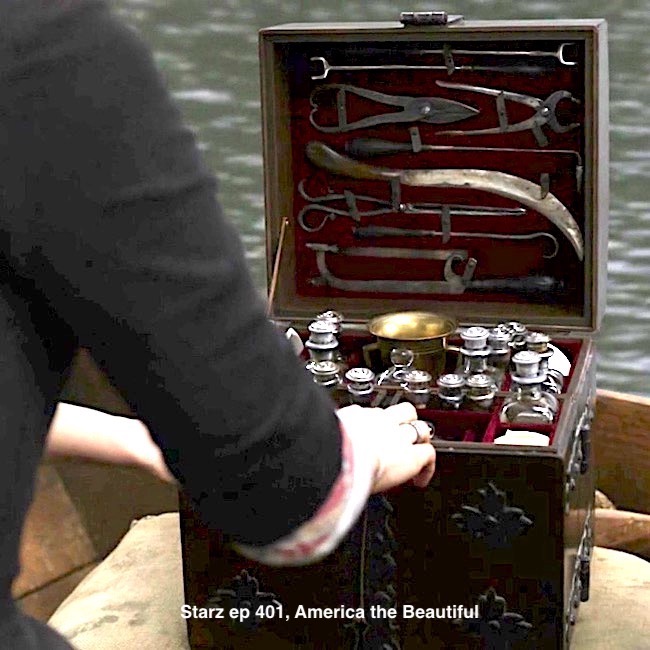

A closer look at the contents of the lid reveals a number of medical instruments that will be useful to a healer (Image B). We use versions of these in gross anatomy teaching labs. I am not 100% certain about all identities, but most are pretty clear.

- green arrow: retractor (a.k.a. surgical rakes or forks) to pull back tissues

- yellow arrow: tissue cutters (e.g. small bone, tendon, ligament)

- red arrow: curved amputation knife

- orange arrow: forceps (possibly tenaculum forceps)

- blue arrow: amputation saw

- turquoise arrow: pliers (tooth extraction)

- violet arrow: cauterizing tool? (unsure about this one)

- white arrow: tenaculum, amniotic hook, tissue hook

NOTE: These instruments appear authentic to the 18th century because handles are made of wood. Handles of that era were also made of ivory. As a rule of thumb, handles made of metal are post-1880s instruments, excepting those wherein handle and blade are fashioned from a single piece of metal.

Image B

The chest’s top shelf is divided into wee compartments containing various bottles, presumably with glass or pewter stoppers, which were common for the era (Image C). Tidily-arranged bottles house various herbs and other medicaments. Rolled linen strips for wound treatment occupy two corners and ceramic/porcelain bowls (for bleeding or perhaps a mortar?) fill the final two. The brass urn could serve various purposes such as a catch basin for bodily fluids. Some brass mortars with “ears”were made in the 18th century although I don’t see a pestle. Do you?

Claire’s thoughts from DOA:

…Inside the front, above the drawers, were row upon row of small, corked bottles made of stone or glass.

…“Oh, Jamie! How wonderful!” He wiggled his feet, pleased. “Oh, ye like it?”

“I love it! Oh, look—there’s more in the lid, under this flap—”

Image C

A middle drawer contains more surgical instruments. From top to bottom, these appear to be (Image D):

- two scalpels

- syringe with ivory handle

- syringe cone made of ivory

- probe

- two scalpels

- two small knives

- scoop

- tongue depressor blade (?)

- scissors

- forceps

Although not all of the items cited in the next quote are shown, those present help us appreciate the monumental gift Jamie has given Claire. Such respect and concern for her calling in life. Another quote from DOA:

“There’s more,” he pointed out, eager to show me. “The front opens and there are wee drawers inside.” There were—containing, among other things, a miniature balance and set of brass weights, a tile for rolling pills, and a stained marble mortar, its pestle wrapped in cloth to prevent its being cracked in transit.“Oh, they’re beautiful!” I said, handling the small scalpel with reverence. The polished wood of the handle fit my hand as though it had been made for me, the blade weighted to an exquisite balance. “Oh, Jamie, thank you!”

Image D

NOTE: I do not spy a fleam among the instruments. The fleam is a tool for blood-letting that would most certainly be in an 18th century medical cabinet (Of course, Claire wouldn’t be caught dead using one!). It is possible that one of the two small knives shown in Image D is a fleam knife with its bump facing downward. These were small knives with a widening of the blade which served to open a vein (Image E).

Image E

Finally, the pièce de résistance! Claire can scarcely breathe. From DOA:

I stared for a moment at the disjointed tubes, screws, platforms and mirrors, until my mind’s eye shuffled them and presented me with the neatly assembled vision.

“A microscope!” I touched it reverently.

“My God, a microscope.”

I understand completely how Claire felt as one of my several teaching duties included microscopic anatomy/histology (Anatomy Lesson #34, The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy), the study of the structure of cells, tissues and organs as they appear in the microscope.

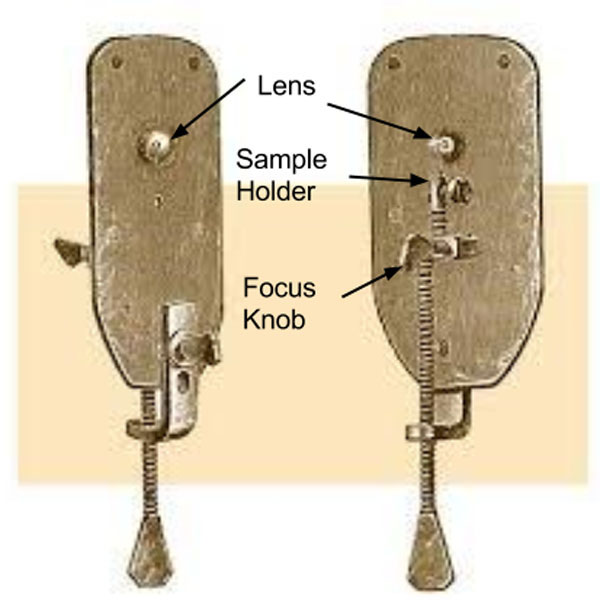

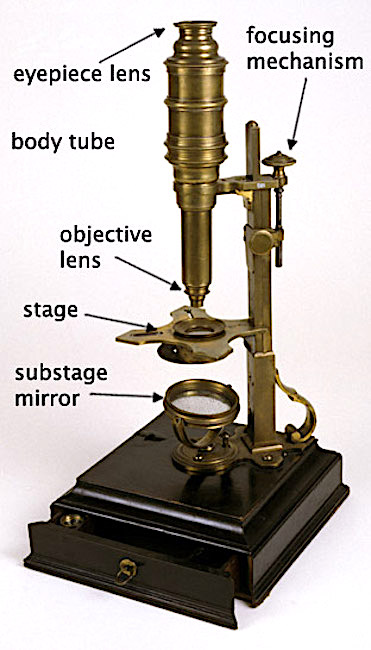

Even more fantastic, Claire’s new microscope is indeed consistent with an 18th century specimen. Delightful! The velvet-lined drawer contains (Image F):

- green arrow: stand with a ring (front right) which holds the tube when assembled

- blue arrow: tube (barrel) of microscope – houses two lenses – an eyepiece lens and an objective lens; these magnify the object being viewed

- red arrow: an objective lens adjacent to two hand lenses

- gold arrow: focusing mechanism (raises or lowers the tube)

- yellow arrow: mirror – reflects light upward to illuminate object being examined

- turquoise arrow: iris diaphragm which controls amount of light reaching specimen

Note: I cannot positively identify a stage, the platform upon which a specimen rests. Perhaps the flat plate under the stand and the round object at back right together form the stage?

Just to clarify, the eyepiece lens is at the tube end under the blue arrow. The objective lens at the opposite end of the tube. This microscope has two lenses so it is a compound light microscope. One objective lens is already on the tube the other is indicated by the red arrow. Each objective lens has a different magnifying power.

Image F

This is so awesome! Assembled, Claire’s microscope would look very much like this 18th century specimen (Image G). Hers appears to be a true vintage microscope and not a facsimile which, IMO, would be too complicated and idiosyncratic to reproduce for TV.

Image G

Finally, Claire murmers to Jamie (DOA book):

“Who did they belong to, I wonder?” I breathed heavily on the rounded surface of a lenticular and brought it to a soft gleam with a fold of my skirt.

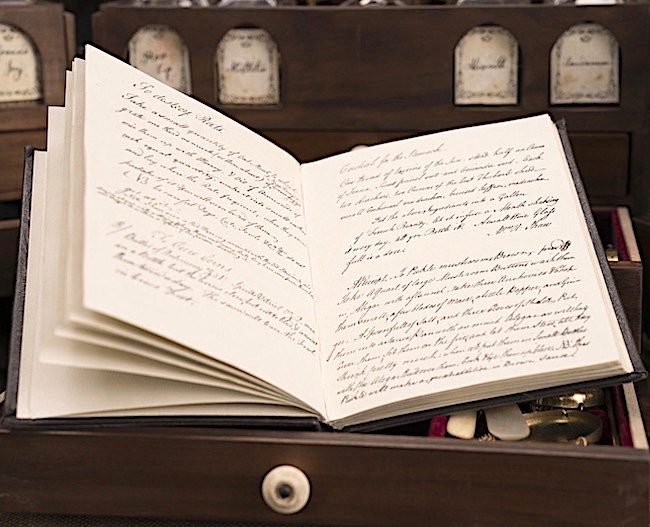

Lifting the top tray of instruments, he revealed another, shallower tray, from which he drew out a fat square-bound book, some eight inches wide, covered in scuffed black leather….Perhaps a quarter of the book had been used; the pages were covered with a closely written, fine black script, interspersed with drawings that took my eye with their clinical familiarity: an ulcerated toe, a shattered kneecap, the skin neatly peeled aside; the grotesque swelling of advanced goiter, and a dissection of the calf muscles, each neatly labeled.

I turned back to the inside cover; sure enough, his name was written on the first page, adorned with a small, gentlemanly flourish: Dr. Daniel Rawlings, Esq.

Indeed, show Claire’s medical box does contain the case book wherein its former owner, Dr. Rawlings, recorded cases, treatments, diseases, etc. (Image H). Outlander Set Decorator, Stuart Bryce, addresses the case book explaining how it was developed:

“…and a book of medical notes from its previous owner which the Outlander Art Department created page by page.

Image H

Although the case book writing is difficult to decipher, the left page is titled: “To Destroy Rats!” Dr. Rawlings would have done well to reference Roger Wakefield’s rat satire (Image I): “go ye rats, go!”

Image I from Outlander Cast

With side panels open and drawers extended, we may fully admire this beautiful and functional medical chest (Image J).

Surprise! Dr. Rawling’s closed case book sits in the bottom drawer beside two ivory handles (tongue depressor blades?).

Way to rock it, Outlander set team!

Image J

Compare Claire’s glorious medical chest (Image J) with this genuine expanded 18th century version (Image K). We must admire Outlander’s attention to detail in recreating their stunning prop. Hard to believe hers isn’t the real deal, although the instruments certainly are. Woot!

Image K

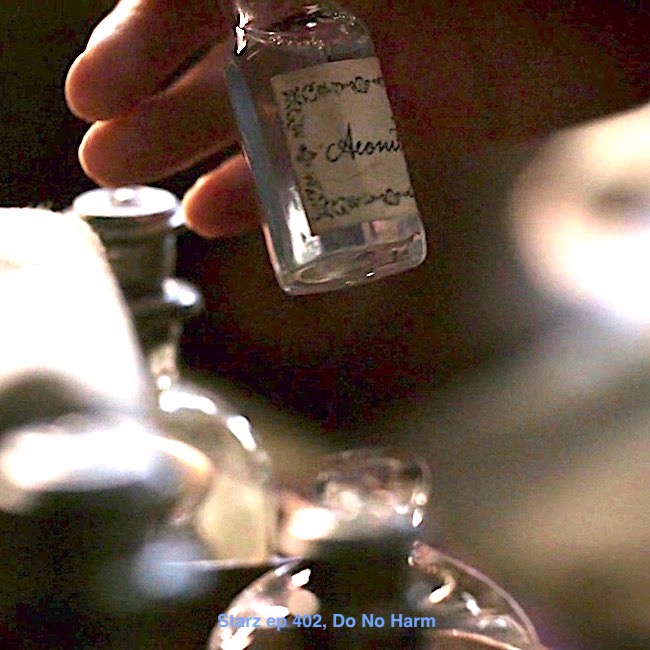

Sad but necessary, Claire’s splendid gift is equipped not only with compounds intended for healing but also at least one that can take life. One bottle contains the deadly poison, aconite (wolf’s bane/monk’s hood), a potent toxin that acts on heart muscle and nerves. A small amount (< 3 gm) is sufficient to quickly kill an adult human.

In Starz 402, Do No Harm, Claire does harm: she uses aconite to hasten Rufus’ demise and spare him a harsher death. Sadly, not how she dreams of using her splendid medical box.

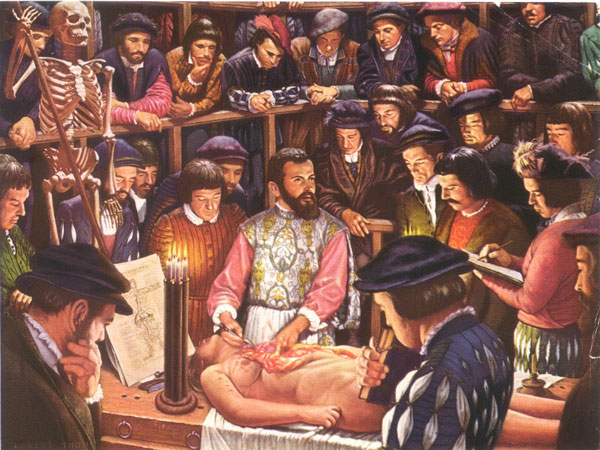

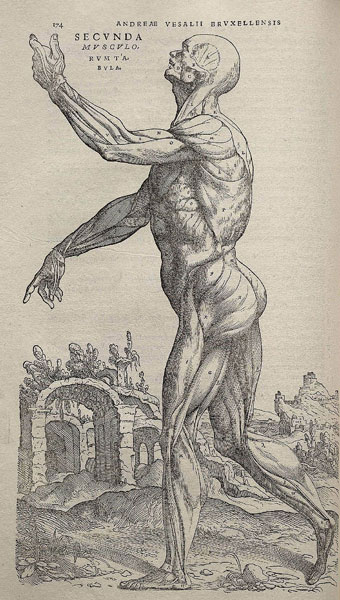

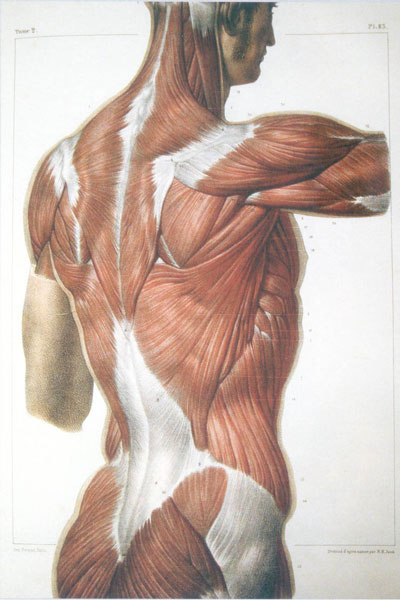

History of the Medicine Chest: Now, don’t run away. I know. History. Ugh! Seriously, let’s consider a wee bit of time travel…

Claire’s medical box represents the continuation of a tradition among western healers lasting 2.5 millennia. Medical kits have been found in ship wrecks dating to the time of King David (450-350 BCE).

In his treatise “On good manners,” Hippocrates (460-370 BCE), Father of Western Medicine, outlines supplies which general practitioners and family doctors should take to house-bound patients. These were carried in chests and other containers:

“All these require arrangements, depending on the materials, so that you can have the tools, the equipment, the metallics and the rest of it already prepared. Because the shortage of these things creates embarrassment and causes harm.”

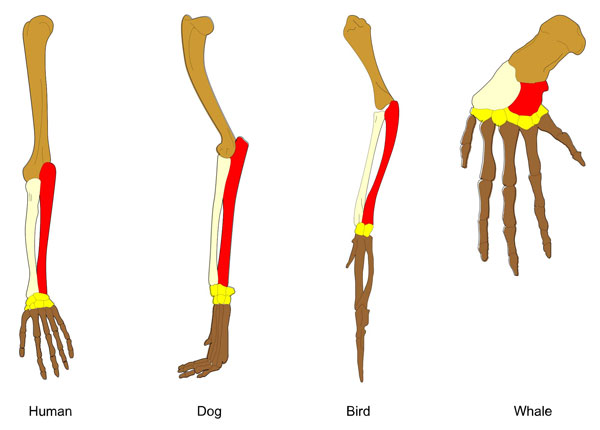

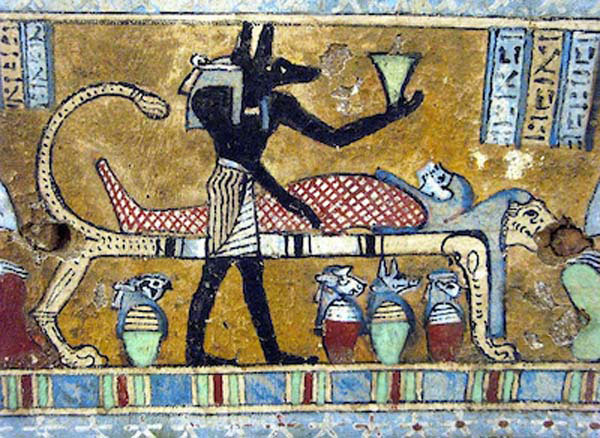

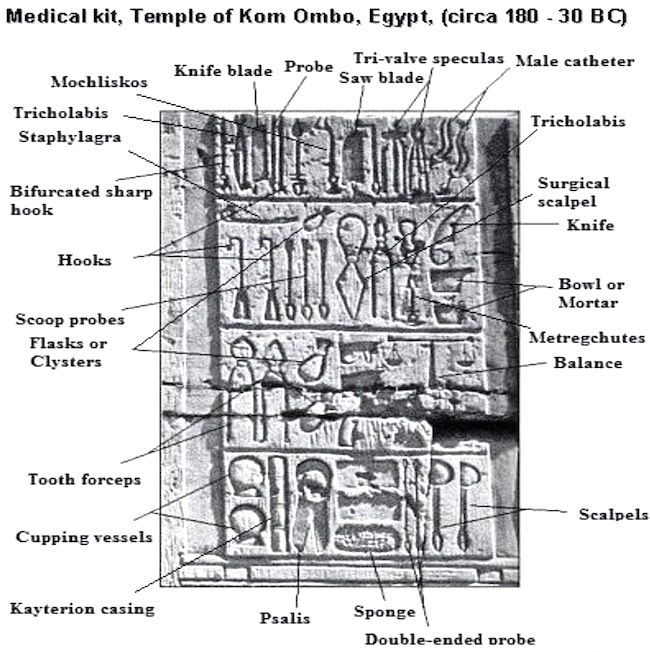

A bit later, a detailed medical kit, including scalpels, hooks and knives, appears in hieroglyphs dating to 180 BCE at the temple of Kom, Ombo Egypt (Image L).

The late 18th and the 19th centuries saw new medical tools to aid diagnosis, treatments and cures. These required a revised method of transport and storage, so the medicine chest, such as Dr. Rawlings’, was conceived, standardized and made more-or-less available to the general population. They were used in the home as well as for travel over land and on the water. Such kits varied from large, such as Claire’s, to small assemblages suitable for etui cases. Today, our in-home medicine cabinets represent a continuation of this tradition.

This tid-bit seems particularly appropriate given the context of Outlander S4. In Canada, the medicine chest has an important, symbolic meaning. Under the terms of a treaty between the Canadian government and First Nations people, the government was required to supply each reserve with a medicine chest. This has been interpreted as an ongoing responsibility for the government to provide healthcare to First Nations people.

Interestingly, even today, all ships governed by the International Maritime Organization must equip and store medical supplies within strict guidelines, an evolution of the earlier seafaring medical chest.

Image L

One final, thoughtful quote from Outlander Community:

The medical box is Jamie’s gift to Claire, which he purchases using one of the Fraser’s jewels. Ever thoughtful and considerate, it is Jamie’s way of recognizing one of his wife’s many talents… allowing her to help those in need and perhaps the first step in helping her to continue fulfilling her passion and calling in life in this new environment.

And, Outlander star Caitriona Balfe recently shared this wonderful sentiment:

“The gift of the beautiful medical box is one of the most touching things Jamie has ever done for Claire.”

Arguably, the only finer gift from Jamie would be this lovely lass!

I wager I am not alone in anticipating many episodes where we see Claire make use of her splendid medicine chest – the gift that keeps on giving!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Photo Creds: Starz episodes 213, 401, 402, 403; www.americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_994411 (images A, K); www.outlandercast.com/2018/06/outlander-filming-locations.html (Image I with memes); www.outlandercommunity.com/insideoutlander/401/ (Images B, C, D, E, F, H, J); www.researchgate.net/figure/Medical-kit-Temple-of-Kom-Ombo-Egypt-circa-180-30-BC_fig3_314079606 (Image L); www.sites.hps.cam.ac.uk/whipple/explore/microscopes/partsofthemicroscope/ (Image G); www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/vintage-lot-blood-letting-fleam-443831256 (Image E)