Anatomy Lesson #44: “Terrific Tunnel – GI System, Part 1”

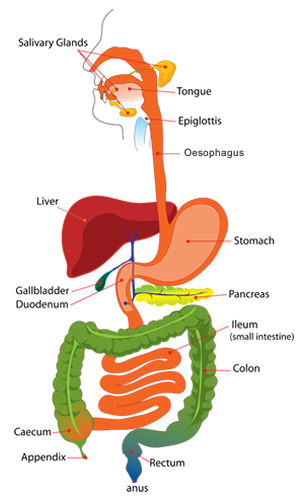

Hello anatomy students! Time to launch a new but thrilling anatomic topic: the GI tract. What is the GI tract (Image A)? Well, it is a complex organ system that enjoys several monikers: alimentary canal, alimentary tract, digestive tube, GI tract, gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal system, and gut. Most anatomists prefer the term gastrointestinal tract or system, but since that term is a bit lengthy, this lesson will shorten it to GI tract.

Image A

Spoiler Warning: there are lots of Outlander images and book quotes within, including one waaaay forward from book eight. A scaredy cat warning appears before hand, so, watch for it!

You can easily scroll to the relaxing cat to skip the whole thing until you’re ready to read MOBY!

The GI tract is a tube extending from mouth through anus (yes, I wrote that and I warrant that team Angus and Rupert used that word, too!). It is divided into the following regions (Image B):

- oral cavity

- oropharynx

- esophagus (oesophagus)

- stomach

- small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum)

- large intestine

- rectum

- anal canal and anus

The GI system includes several additional organs that are associated with the GI tract:

- major salivary glands

- liver

- gallbladder

- pancreas

Image B

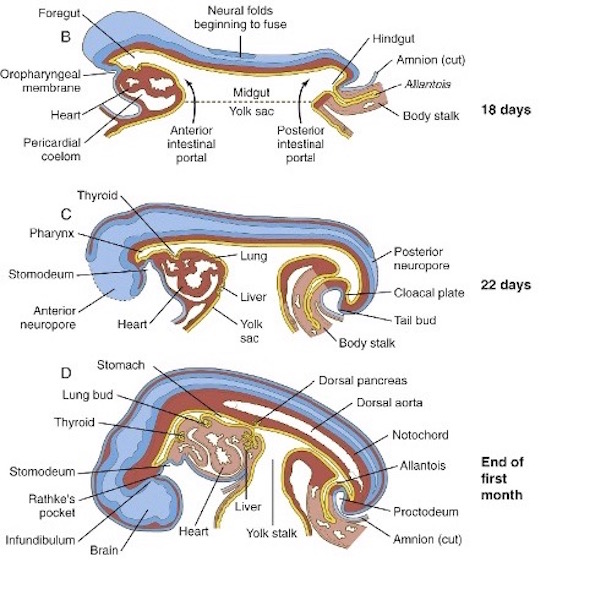

GI Embryology: You might wonder why the last four organs belong to the GI system. This occurs because during embryogenesis, these organs develop as outgrowths of the developing GI tube. After birth, they retain connections with the parent GI tract via ducts (hollow tubes). Parental offspring!

Embryogenesis of the GI tract is extraordinarily complex but consider this simplified version (Image C – gold layer):

- The human embryo starts as a flattened sheet of layered cells which folds and expands due to cell division (and death) directed by chemical growth factors.

- By 18 days, the future gut expands at the head end as the foregut and a second hollow, the hindgut, develops at the rear. The open midgut lies between the two hollows.

- By 22 days, the gut assumes a more tube-like configuration. The early liver appears.

- By 30 days, the nascent pancreas appears.

- Over the next days and weeks, the foregut differentiates into pharynx, esophagus, stomach, part of small intestine, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

- Midgut develops into the rest of small intestine, and part of large intestine.

- Hindgut gives rise to the remaining large intestine, rectum, anal canal, and part of anus.

Image C

The Tube (not the one in London!): Think of the mature GI tract as a long, hollow tube, albeit one that is variously folded and dilated. The tube shown in Image D has a wall made of zirconium but, consider that the space inside the tube is an extension of the outer world. Yes? Same is true with the GI tract: from mouth through anus, the lumen (space) inside the GI tract tube is an extension of the outer world. Even as ingested materials disappear after swallowing, anything in the lumen technically remains outside the body until it crosses the wall of the GI tract. Make sense? Yay!

Image D

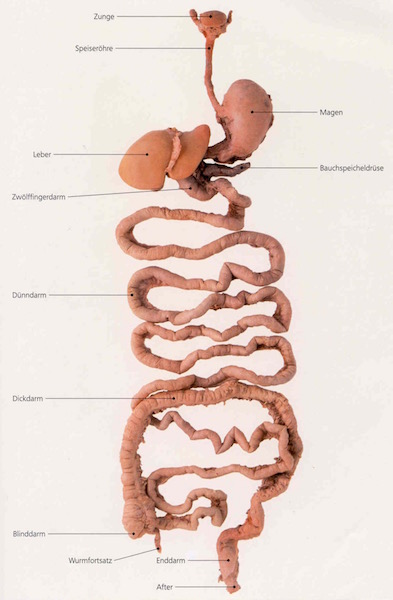

Length: The adult GI tract is also very long. Just how long is it? In adults, it measures 8.3 m (27’+) – almost the height of a three-story building! Much of its length is highly folded so it nicely tucks within the abdominal cavity. A Body Worlds exhibit (Image E) shows an expanded view of the GI tract and its associated organs. German labels reflect the language of the show’s creator, Gunther von Hagens. Lay the tube out straight, and it approaches 27’ in length.

The length isn’t a fluke of nature, rather, it is required for digestion of foodstuffs, absorption of nutrients, and preparation of residues for elimination. There are also many more functions provided by associated organs of the GI system. More about such functions soon.

Image E

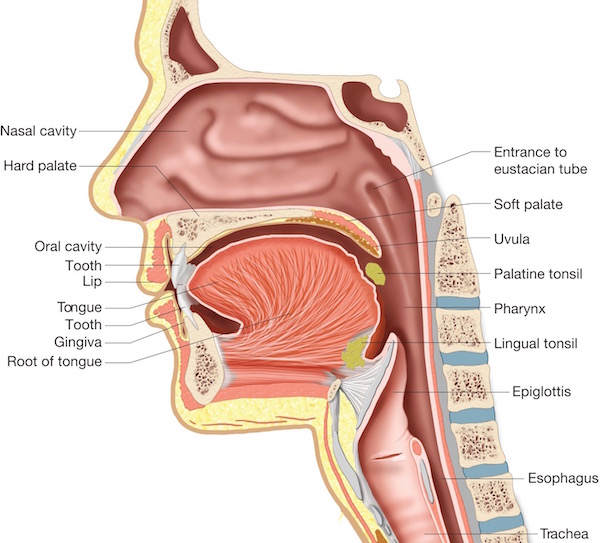

So, with those issues behind us (har har), the lesson begins and ends with the oral cavity or mouth. The mouth includes many components: inner lips, inner cheeks, gums, hard and soft palates, floor of mouth, tongue and teeth (Image F). Let’s start with the lips.

Lips: Visible flaps at the mouth opening, the soft pliable lips are important additions to the GI tract because they augment food intake, chewing, and articulations as in speech (Image G). Hopefully, the lip-flash doesn’t freak you out!

People generally think of the lips as the part to which lipstick is applied. But, anatomists hold that the lips are more extensive.

Image G

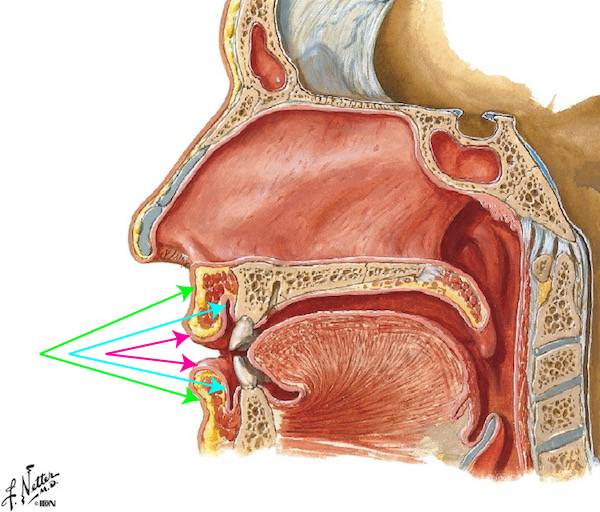

Anatomical lips include not only the lipstick canvas, known as the vermillion zone (Image H – pink arrows), but also the hair covered flaps above and below the vermillion zone (Image H – green arrows) as well as the moist and red inner surface of these flaps (Image H – blue arrows).

The hairy outer lip is part of the face which was presented in an earlier lesson (Anatomy Lesson #14, “Jamie and Claire” or “Anatomy of a Kiss”). The inner lips belong to the oral cavity and are lined with mucous membrane or mucosa (Anatomy Lesson #42, “The Voice – No, not that One!”). The vermillion zone is the transition area between these two surfaces.

Image H

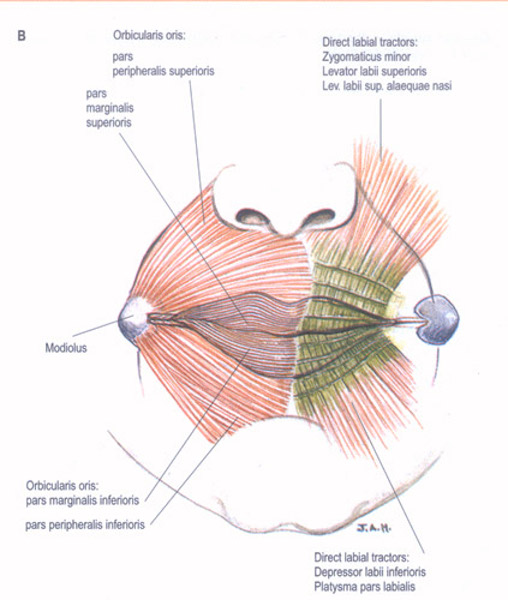

Lips are equipped with orbicularis oris (Image I), a major muscle mass, rendering them highly mobile. For decades, orbicularis oris was described as a sphincter muscle encircling the opening of the oral cavity, a description that remains rampant on today’s Internet. Modern dissections have shown this description to be insufficient. Rather, orbicular oris is divided into four quadrants, each containing both circular and direct (diagonal) muscle fibers, lending an amazing ability to purse, pucker, and pout. For a more thorough consideration of orbicularis oris, visit Anatomy Lesson #14, “Jamie and Claire or Anatomy of a Kiss.”

Although not shown in Image I, lips are also provided with seven pairs (that’s 14 total!) of muscles that elevate (lift), depress (lower), and/or retract (pull back) the lips. Very mobile structures, the lips!

Image I

Jamie provides a fantastic example of pursed lips as he endures rambling threats and ignoble insults from BJR (Starz episode 109, The Reckoning). No choice – Cap. Mad Man holds a knife to his beloved Claire! Puckering requires simultaneous contraction of direct and circular orbicularis oris muscle fibers. ?“Nobody does it better … Nobody does it half as good as you. Baby, you’re the best!” ?

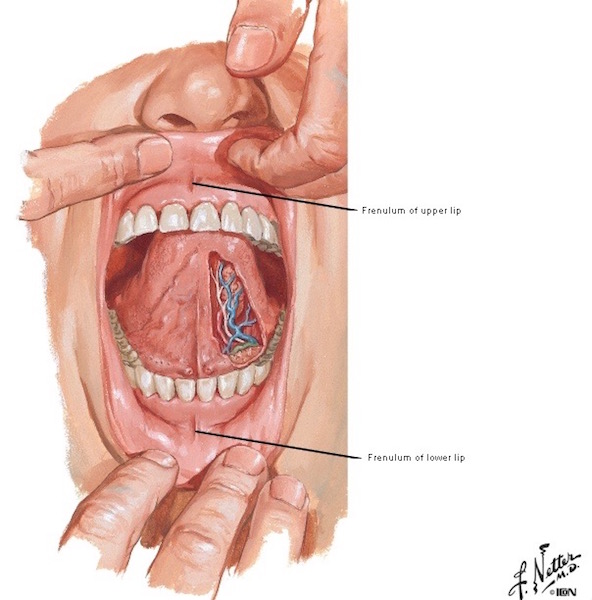

Lastly, lips are anchored by webs of mucous membrane: a frenulum of the upper lip and a frenulum of the lower lip (Image J).

Image J

Lips are highly tactile structures imbued with numerous sensory receptors which detect light touch, deep pressure, pain, vibratory sense, heat, and cold. These many tactile attributes help our lips close, grip objects, and engage in kissing and other acts of intimacy (Image K). Ha!

Image K

Because lips are highly innervated and possess startling mobility, they enjoy a prehensile-like ability to grip things, even items they should avoid gripping (Starz episode 101, Sassenach). Small Saucy Sassynach!

Outlander kisses would be neither as passionate nor as (ahhhh!) satisfying sans nimble muscles and sharp tactile sensibilities of the lips. Smack down!

Jamie and Claire share many kisses, especially during Outlander Season 2 (Starz episode 210, Prestonpans). But a quote from Dragonfly in Amber book says it all – a bit of a love poem by Catullus:

Then let amorous kisses dwell

On our lips, begin and tell

A Thousand and a Hundred score

A Hundred, and a Thousand more.

I love writing about our fav couple’s lips, but we must move on. Sigh!

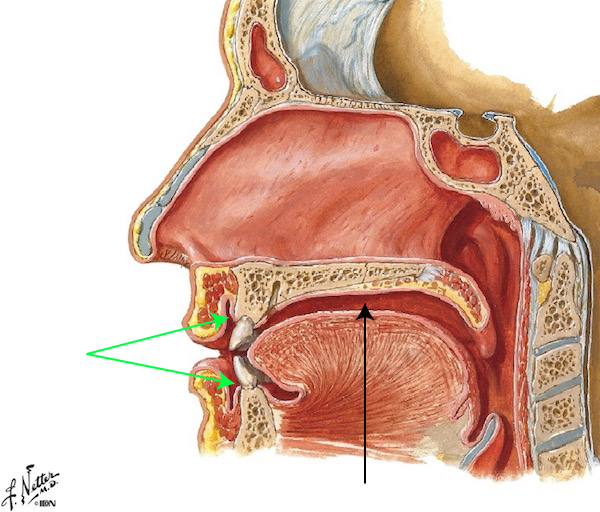

Oral Cavity: Before describing structures of the mouth, it is important to further define the oral cavity. The oral cavity is divided into two parts. The oral vestibule is a slit-like space between teeth and inner lips and between teeth and cheeks (Image L – green arrows). The oral cavity proper is the larger slit-like space behind the teeth (Image L – black arrow).

Image L

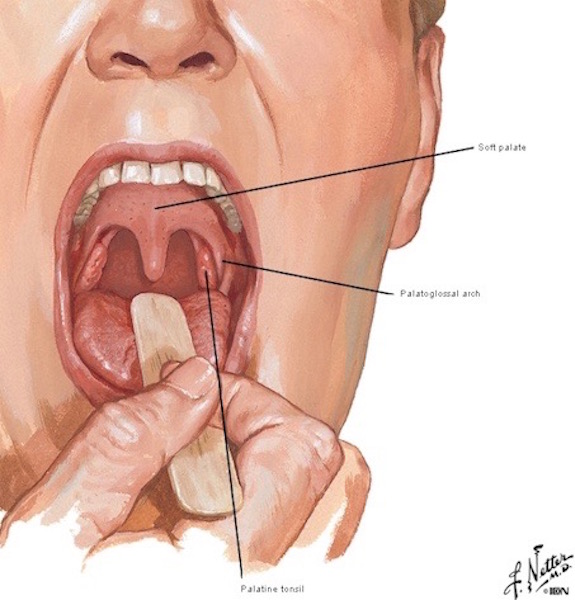

Oral Cavity Proper: However, with jaws open, the oral cavity dramatically expands into a rather large cavern (think foot-in-mouth). Gazing into the oral cavity proper, it starts at the vermillion zone and ends at the paired palatoglossal arches, two mucosal folds descending from the soft palate to the tongue (Image M). See the paired palatine tonsils (we have three pairs of tonsils)? These lie outside the oral cavity.

Image M

Wanna see Jamie’s proper oral cavity? Of course ye do! Jamie lets out a big-old howl after that bratty MacDonald lad slices and dices his left side (Starz, episode 110, By the Pricking of My Thumbs). Ouch, that hurts! Jamie is in for it now – his usually not-a-silent wifie willna appreciate such blatant butchery. Say ahhhhh, lad!

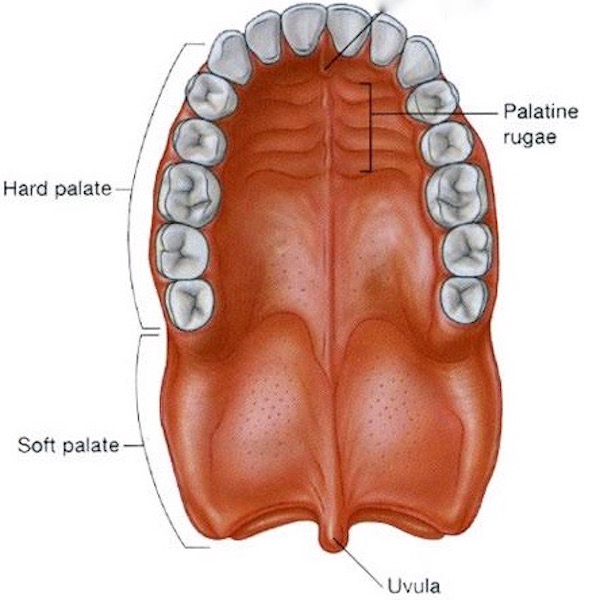

Palates: The roof of mouth is divided into two palates: an anterior hard palate, so named because its mucosa overlies bone, and a posterior soft palate which lacks bony underpinnings. Image N shows the palates as if you sat on the tongue and stared upward. The soft uvula is a midline structure suspended from the soft palate. The two palatoglossal arches drop right and left from the uvula.

Here is an interesting fact: The hard palate is characterized by permanent folds known as rugae. These ridges are stable and unique for each person suggesting they could be used for identification purposes. Their human function is not clear but is probably related to mastication (chewing).

Try This: With mouth open, use tip of tongue or finger to feel where hard palate and soft palate meet. Carry a flashlight/torch to a mirror. Open your mouth, but shine the light directly into the mirror; light reflects off the mirror and into your mouth. Identify your uvula, the dangly bit hanging from the roof of the soft palate. Several small muscles control it during swallowing, speech, etc. My fav muscle is the itsy bitsy teenie-weenie tensor veli palatini. <G>

Image N

Mucous Membrane: Consider the mouth’s interior. Every surface, except teeth, is covered with mucous membrane, a red, shiny, wet, and sensitive surface (Image O). The membrane appears red because it has a rich blood supply. It is wet because saliva bathes its surfaces. It is shiny because saliva reflects light. It is sensitive because it is supplied with numerous sensory receptors.

With some exceptions, the mucous membrane of the entire oral cavity is non-keratinized (Anatomy Lesson #5, “Claire’s Skin” – “Ivory, Opal and White Velvet”), meaning its cells do not contain keratin. However, mucous membrane of gums near the teeth, top of tongue, and hard plate contain keratinized cells. Why? Because they are subject to abrasion during mastication. Keratin is an intracellular protein which hardens cells, making them resistant to abrasion. Make sense? Yay!

Remember when Angus Mhor administers a methodical beating to Jamie in Castle Leoch’s great hall (Rupert does the dirty deed in Starz episode 102, Castle Leoch)? Diane writes about Jamie’s oral mucosa in Outlander book. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, if you’re not reading Diana’s books, you are missing out on gobs of anatomy!

“Is your mouth cut inside too?” “Unh-huh.” He bent down and I pulled down his lower jaw, gently turning down the lip to examine the inside. There was a deep gash in the glistening cheek lining, and a couple of small punctures in the pinkness of the inner lip. Blood mixed with saliva welled up and overflowed.

Try this: Return to the mirror with a flashlight. Open mouth and inspect its lining. See that the mucous membrane surfaces are moist, shiny, and red. We all known how tender they are. With tip of tongue explore the surfaces of cheeks, floor of mouth, and inside of lips. All surfaces are smooth and moist excepting the rougher hard palate, gums near teeth and dorsum of tongue.

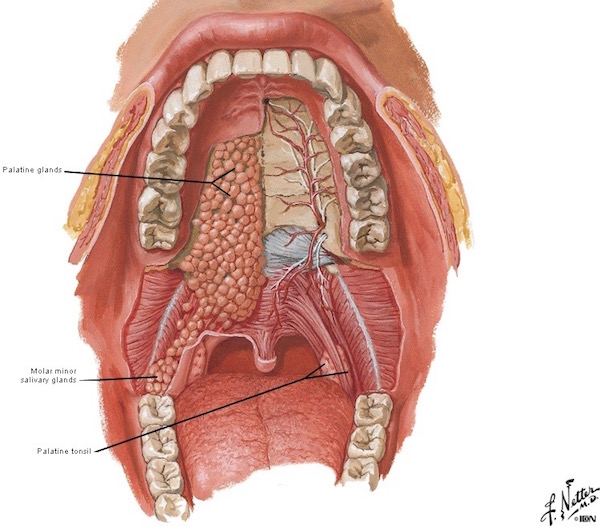

Image O

Minor Salivary Glands: Image P demonstrates a little known fact: deep to the mucous membrane, the entire mouth is riddled with thousands of minor salivary glands; these microscopic entities are much smaller than Image P implies. Tiny ducts (channels) lead from the glands, pierce the mucous membrane, and open into the oral cavity. Minor salivary glands produce and secrete saliva to moisten oral surfaces. Some of these glands specialize in producing mucus, a thick secretion rich in glycoproteins (protein molecules with carbohydrate side chains) which renders the saliva slippery.

Try This: Return to the mirror, grasp and evert one cheek (Ha, ha. No, not that one!). Can you see tiny surface humps and bumps? These are caused by aggregations of minor salivary glands.

Image P

Tongue: The human tongue is an organ. What is an organ? In anatomy, an organ isn’t a musical behemoth equipped with large keyboard and foot pedals; rather, it is a collection of tissues joined into a structural unit that serves a common function(s).

Ably demoed by Miley (Image Q), the tongue is rather large. We use it to help chew (as in mixing food with saliva), swallow, speak, and taste. And, to be bratty, of course!

Image Q

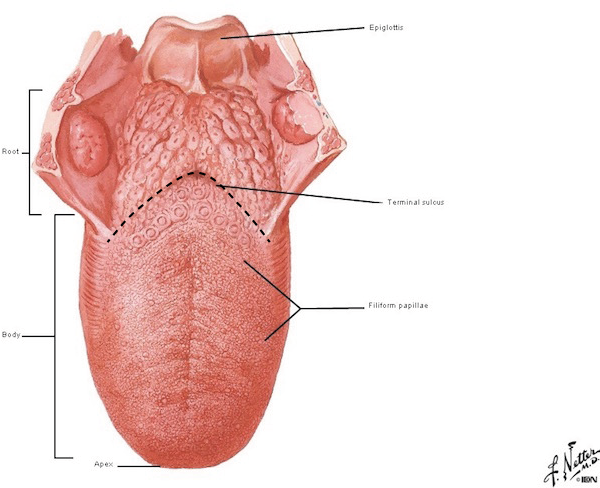

The mature tongue is divided into (Image R):

- Body – oral part (anterior 2/3)

- Apex – the tip (part of the body)

- Root – pharyngeal part (posterior 1/3)

The tongue is an extraordinary organ, arising from two different embryonic anlage (rudimentary parts) which fuse during development: one part gives rise to body and apex, and a second part produces the root. The two parts fuse leaving a remnant, the terminal sulcus (Latin meaning end groove), an inverted, V-shaped groove (Image R – dashed lines) on dorsum of tongue.

Take another look at Miley’s tongue (Image Q); the part you see is body and apex. The tongue root is not visible because it drops backward and downwards, out of view.

The tongue body has two different surfaces. A protected ventral (under) surface is covered with thin mucous membrane. The dorsum (top) of tongue is covered with mucous membrane but it is rough. Do you remember why?

Image R

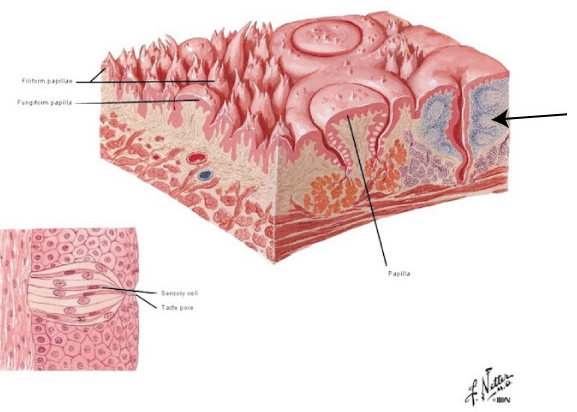

Tongue Papillae: The dorsum of tongue is rough because the surface is covered with a mess of tiny bumps, the papillae (Latin meaning nipple). Image S is a vertical section through back of tongue showing surface papillae. Human tongues have four different types of papillae: fungiform, filiform, foliate, and circumvalate (the big guy marked papilla in Image S). Foliates are present on the sides of our tongues – they do not appear in the image

Papillae derive their names from their shape. Fungiform look like mushrooms, filiform resemble filaments, foliate are leaf-like, and the humongous circumvalate (valate) are bound by a deep circumferential moat.

BTW: See the blue ovals near the right edge of Image S (black arrow)? These are lingual tonsils . We have a large mass of tonsils embedded in each side of our tongue just posterior to the sulcus terminalis. Yes, we do!

Taste Buds: All papillae except the filiform type harbor taste buds, units embedded in the covering cells of the mucous membrane. The cells of filiform papillae are keratinized to help grip food particles and to protect the tongue dorsum during mastication. The human tongue has between 2,000 and 8,000 taste buds. But, here is an interesting Fascinating Fun Fact: taste buds are also found in the mucosa of soft palate, esophagus, inner cheeks and epiglottis (Anatomy Lesson #42, “The Voice – No, not that One!”)! Yep, ’tis true

Viewed vertically, taste buds resemble sections of a peeled orange (Image S – lower left), and are composed of supporting and sensory cells. A tiny taste pore opens into the oral cavity. Food molecules, delivered as a salivary cocktail, reach the taste pore, sensory cells detect the molecules and depolarize (change in electrical charge). this stimulates nearby nerve fibers which carry the impulse to the brain where it is interpreted as flavor. Whew!

Try this: Return to the mirror with a flashlight. Open your mouth and peer closely at the tiny papillae covering the tongue dorsum. Look carefully, you will likely see larger fungiform papillae scattered among the smaller, more numerous filiform type. You will not see the foliate because they are far back at the sides of tongue. If you are truly adventurous, place forefinger on the tongue dorsum and push it backwards as far as possible. Feel the rough bumps on either side? These are the circumvalate papillae. Rah!

Image S

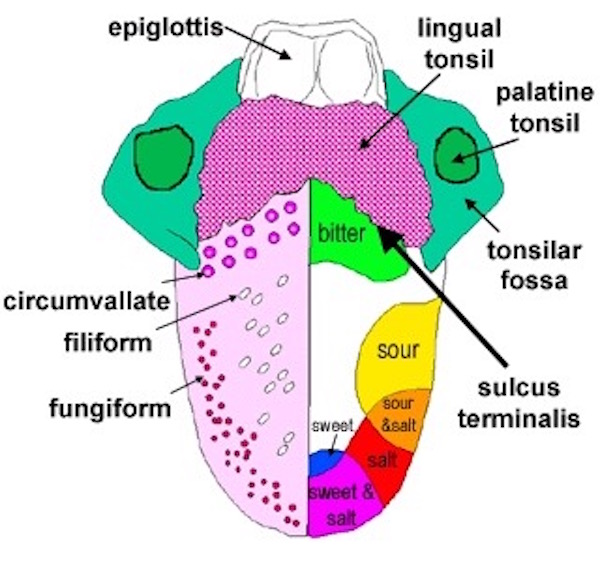

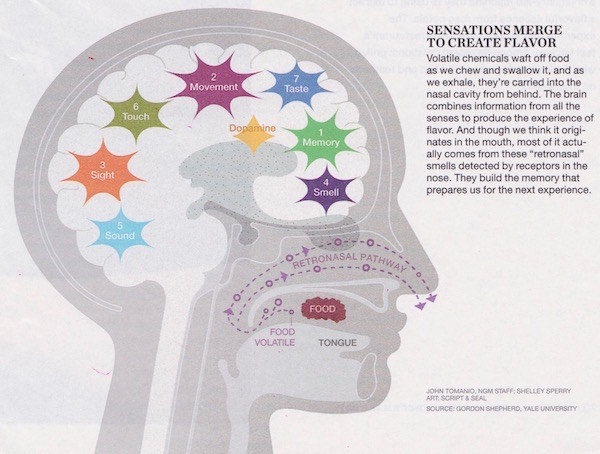

Flavors: Since 1901, students have been taught that human taste buds detect four different flavors: salty, sour, bitter, and sweet. Recent lobbying by researchers have added a fifth flavor, umami (savory). And, for over a century, taste bud distributions were mapped out on the tongue dorsum to show where these flavors are detected (Image T). This myth has been debunked as research shows we can detect all five flavors anywhere on the dorsal tongue albeit more intensely in some regions than others. And, the detection of flavors is far more complex than the five types provided by taste buds, as we shall consider at lesson’s end.

Image T

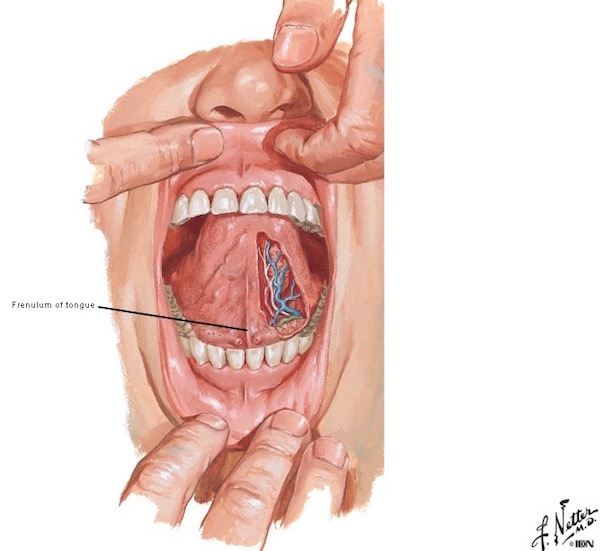

Ventral Tongue: The ventral (under) surface of tongue isn’t exactly beautiful, but it is covered with a thin mucous membrane similar to inside of cheeks and lips. This surface exhibits several folds and a midline lingual frenulum, a fold of mucous membrane which anchors the tongue to limit its movements (Image U). Bluish longitudinal squiggly ridges are created by large, underlying lingual veins.

Image U

BOOK SPOILER WARNING!

Skip the next paragraphs and scroll down to the relaxed cat if you don’t want to read a quote from Diana’s eighth book…

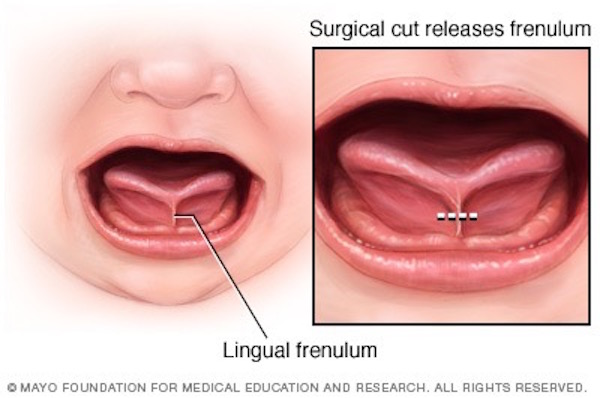

During embryogenesis, the lingual frenulum is quite long. Programmed cell death within the frenulum causes it to shorten (Fact: embryonic development involves gobs of programmed cell death). Occasionally, the programming goes awry and the frenulum fails to shorten leaving its owner tongue-tied (Image V – left side).

Known as ankyloglossia (Greek for fused tongue or fixed tongue), a simple case requires a clip through part of the lingual frenulum (Image V) to release the tongue from its tether (Image V – right side). This procedure is known as a frenotomy.

Diana provides! Claire performs this surgery on a character (no name!) from book eight, Written in My Own Heart’s Blood, known by faithful readers as MOBY:

I’m going to do just a frenotomy, at least for now. That is a very simple operation; it will literally take five seconds…. I had a tiny cautery iron, its handle wrapped in twisted wool… I had a fine suture needle, threaded with black silk, too, just in case. The frenulum is a very thin band of elastic tissue that tethers the tongue to the floor of the mouth, and in most people it is exactly as long as it needs to be to allow the tongue to make all the complex motions required for speaking and eating, without letting it stray between the moving teeth, where it could be badly damaged … the frenulum was too long and, by fastening most of the length of the tongue to the floor of her mouth, prevented easy manipulation of that organ.

Go Diana!

Try this: Return to “mirror-mirror-on the wall”. Open mouth and inspect undersurface of tongue and its anchoring lingual frenulum.

Image V

We’ll leave the tongue with a timely quote from Dragonfly in Amber, Diana’s second book:

He didn’t break away from the kiss, but held himself motionless, gently exploring my lips, the tip of his tongue caressing, barely stroking. I touched his tongue with my own, and held his face between my hands.

Yep! a verra useful organ, the tongue (Starz, episode 107, The Wedding). Snort!

Teeth: Moving on… Human teeth are designed to grip, cut, tear, and crush food in preparation for swallowing and digestion. Chewing grinds food into smaller bits so we can swallow a food bolus more easily and to expose more food surface to digestive enzymes. Ever tried to swallow a big chunk of poorly-chewed food? Even a spoon-full of sugar won’t help it go down. Stuuuuck!

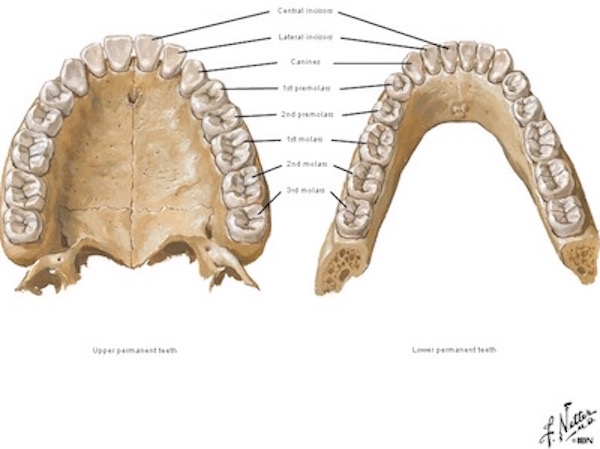

Permanent (adult) teeth fall into four different groups (Image W): incisors, canines, premolars and molars. Incisors cut, canines tear, and premolars and molars crush food.

Anatomy Lesson #26 “Jamie’s Chin – Manly Mentus,” discussed teeth in detail, but to briefly review, an adult human is potentially equipped with 32 teeth (things do go awry). The maxillae (upper jaw) contain eight teeth per side. Ditto for the mandible (lower jaw).

Baby Teeth: As you know, youngsters have deciduous (baby or milk) teeth, meaning they are shed with age. There are 20 deciduous teeth, five per side in the maxillae and five per side in the mandible. Baby teeth have no premolars and only two molars per side, top and bottom, hence, a different overall count.

Claire gives Jamie an anatomy lesson about good teeth in Dragonfly in Amber book:

Eat those first, though; they’re good for you.” He shared the Highlanders’ innate suspicion of fresh fruit and vegetables, though his great appetite made him willing to eat almost anything in extremity. “Mm,” he said, taking a bite of one apple. “If ye say so, Sassenach.” “I do say so. Look.” I pulled my lips back, baring my teeth. “How many women of my age do you know who still have all their teeth?” A grin bared his own excellent teeth. “Well, I’ll admit you’re verra well preserved, Sassenach, for such an auld crone.”

Image W

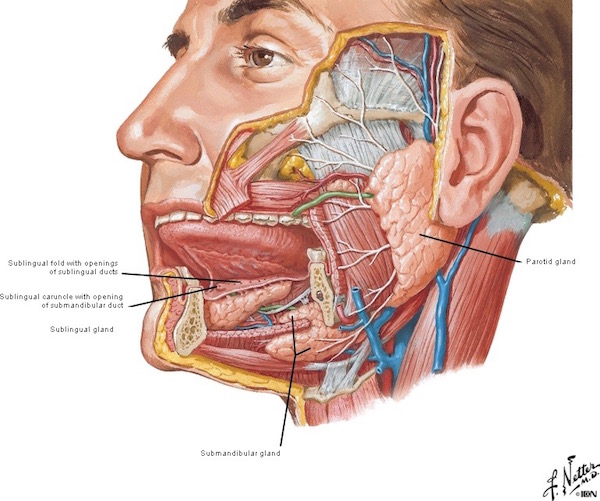

Major Salivary glands: Because we have minor salivary glands, there must be “The Majors.” Actually, we have three pairs of major salivary glands but all reside external to the mouth. Then, why discuss them with the oral cavity? Because, as stated earlier, major salivary glands began existence as outgrowths of the embryonic oral cavity. As such, they are equipped with ducts that drain their secretions into the mouth.

What are those secretions? Well, saliva, of course. But, you should know that saliva isn’t just a slimy mixture of mucus, water, and ions, it also contains an enzyme that begins digesting starches before they leave the oral cavity. Known as salivary amylase and earlier as ptyalin (from Greek ptualon meaning spittle), this enzyme cleaves carbohydrates into smaller molecules. Once again, mom’s adage to chew your food slowly applies not only to breaking it down for easier swallowing but to mixing it with ptyalin to begin carbohydrate digestion. Smart lass, your mam.

The paired major salivary glands include parotids, submandibulars, and sublinguals (Image X). Parotid glands wrap around the ramus of each mandible (lower jaw bone), just anterior to the ear. Did you know, during a mumps infection, the offending virus takes up residence in the parotid glands? Submandibular glands lie in floor of mouth near the angle (back corner) of the mandible. Sublingual glands are located in the floor of the mouth but under the tongue. In case you forgot parts of the mandible, you can read about them in Anatomy Lesson #26, “Jamie’s Chin – Manly Mentus.

Image X

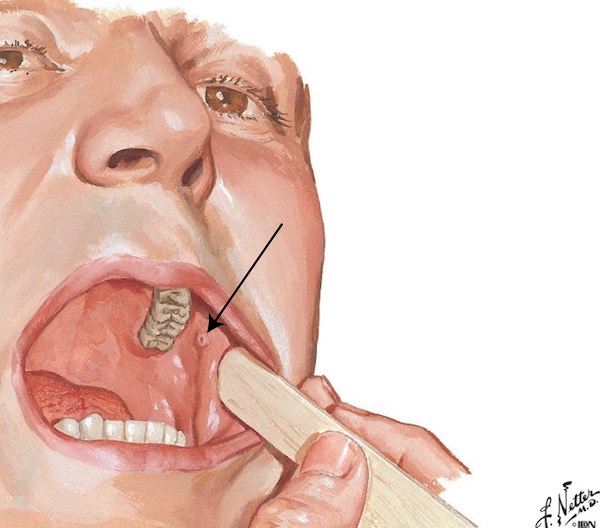

Parotid ducts pierce the cheek mucosa and empty into the oral cavity adjacent to the upper second molars (Image Y – black arrow).

Image Y

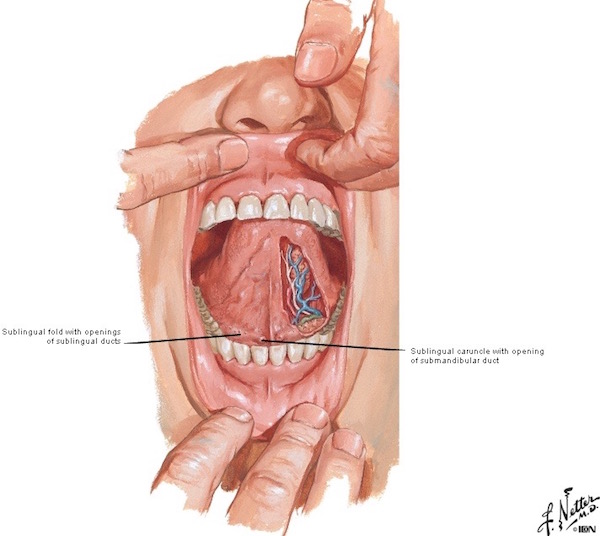

The floor of mouth is equipped with a pair of sublingual folds, pleats of mucous membrane (Image Z). Each submandibular duct opens onto a sublingual caruncle, an anterior knob on each sublingual fold. Multiple, small sublingual ducts open onto each sublingual fold.

Try This: Place tip of tongue against cheek mucosa near the upper second molar tooth. Can you feel a small blip in the mucous membrane? This is the opening of a parotid duct, also known as Stensen’s duct. Place tip of tongue in floor of mouth and wiggle. Do you feel a long ridge of mucosa on each side? This is the sublingual fold. Return to the mirror, open mouth and lift tongue. Look for the sublingual folds on each side of the floor of mouth. At the front of each fold is a sublingual caruncle. Opening onto each caruncle is the submandibular gland duct, also known as Wharton’s duct. You probably won’t see openings of the sublingual ducts because they are small. Just so you know, stones can form in salivary gland ducts just as they do in kidney and gallbladder.

Image Z

Saliva serves purposes other than moistening mucous membranes of the mouth and providing enzymes. These new uses are a bit more, social or antisocial as the case may be.

Gleeking: Ever hear of gleeking? Gleeking is the ability to propel a stream of saliva out through the submandibular duct orifices. Saliva accumulates in the submandibular glands and is forcefully expelled as the tongue compresses the glands. Some folks can gleek on both sides, others on just one. Take a peek at this amazing YouTube example! Talented gleeker!

Enticing Thoughts: As you know from Pavlov’s dog studies, eating stimulates salivary glands, but enticing thoughts may also flood the entire mouth with saliva.

Consider Malignant Marley, BJR’s own personal Icky-Igor, in Outlander book and Starz episode 115, Wentworth Prison:

Marley, who had begun to pant rather heavily during the search, stopped and wiped a thread of saliva from the side of his mouth. I moved as far away as I could manage, disgusted.

Eeeewww, poor Claire!

Great Expectorations or Spitting #1: Spitting is another great use of saliva! Again, not your typical biological function, but it has its purposes! Starz episodes provide three excellent examples of such mouth showers. Claire is the first spitter of the series, giving that redcoat bastard a wet blast right between the eyes (Starz, episode 101, Sassenach)! Well, he did have her between a rock and a hard place! Hee hee!

Spitting #2: Next, Murtagh hawks an awesome, audacious loogie at Dougal (Starz episode 109, The Reckoning). He has no use for this MacKenzie war chief and does not ken why it takes Jamie until another 20 episodes to get rid of this Revolting Relative!

Spitting #3: Black-Jack gets a well-aimed juicy one from Jamie (Starz, episode 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul). And, why not? Jamie has little to lose because Claire is safe and BJR will proceed to extract his measure of agony no matter what. Just look at Jamie’s puir hand! Gah!

Drawing this lesson to a close, here is a final tidbit. Taste buds detect the five basic tastes and their combinations, but more flavor detection comes from hundreds of nasal receptors that activate as food chemicals are breathed out through the nose (Anatomy Lesson #28, “The Savvy Sniffer – Claire’s Nose Knows!”). Detection of flavors is actually a complex combination of memory, movement, sight, smell, sound, touch and taste (Image AA). Amazing!

So, remember this take-home message: the entire oral cavity and its associate elements are designed for the intake, mastication, taste, and breakdown of foodstuffs. These essential steps await further processing by the terrific tube! Very important, the oral cavity. I am grateful for mine every time I take a bite of something yummy. Mr. Bean’s complex poem says it all:

Food – by Mr. Bean

Food is good.

Hee, hee! Next Anatomy Lesson will continue with the GI Tract. TTYL!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Photo creds: Starz, Gray’s Anatomy, 39th ed. (Image I), National Geographic, Dec. 2015 (Image AA), Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy, 4th ed. (Images H, J, L, M, O, P, R, S, T, W, X, Y, Z), www.anatomy-bodychart.us (Image F), www.beyondthedish.wordpress.com (Image C), www.bodyworlds.com (image E), www.brettelliot.com (Image B), www.channelingerrik.com (Image of scaredy cat), www.histology.leeds.ac.uk (Image T), www.keyword-suggestions.com (Image N), www.mayoclinic.org (Image V), www.onedio.co (Image G), www.singtheidol.com (Image Q), www.smithsonianmag.com (Image O), www.smt.sandvik.com (Image D), www.superteachertools.net (Image K), www.youtube.com (Image A),