By Dr. Karmen L. Schmidt

Greetings fellow travelers! Welcome to today’s Anatomy Lesson #48, “The Big Guy,” better known as large intestine. Much is known about large intestine but today’s lesson covers only a tad; otherwise, the lesson would rival one of Diana’s big books! <g> This topic may prove uncomfortable for some, but I hope you lasso any reservations and read this fascinating stuff. For those not sure, Jamie appears to give a wee warning before the most – ahem – personal bits. The good news: Outlander quotes, scenes, and book spoilers await. Yay!

Last lesson, Anatomy Lesson #47, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!” – GI Tract, Part 4, we learned that small intestine ends after ileum, the site where large intestine begins.

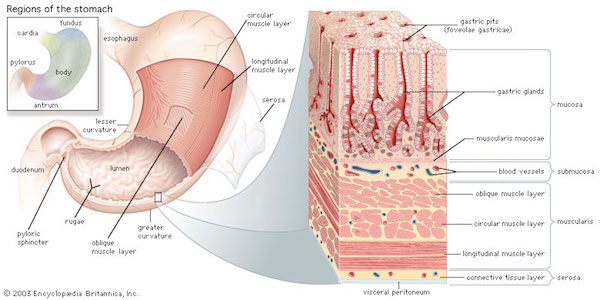

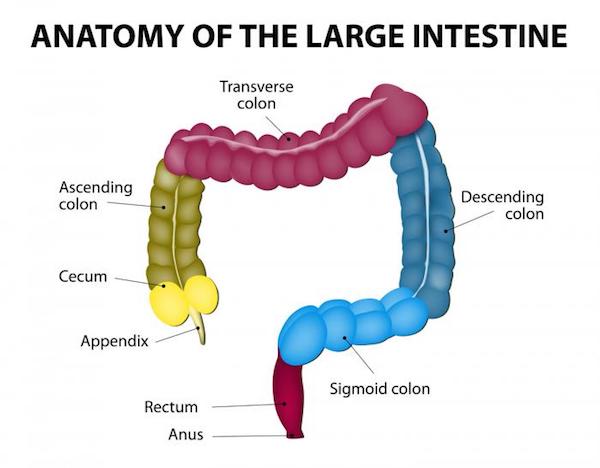

Divisions: As always, anatomical descriptions and definitions are a must! Large intestine is shorter (5 ft) than small intestine (20 ft) but its diameter is larger (3”) compared with the little guy (1-2”), hence the name. Large intestine is divided into the following regions (Image A):

- vermiform appendix (cream & green)

- cecum (yellow)

- colon

- ascending colon (green)

- transverse colon (mauve)

- descending colon (dark blue)

- sigmoid colon (light blue)

- rectum (purple)

- anal canal (not labelled)

Image A

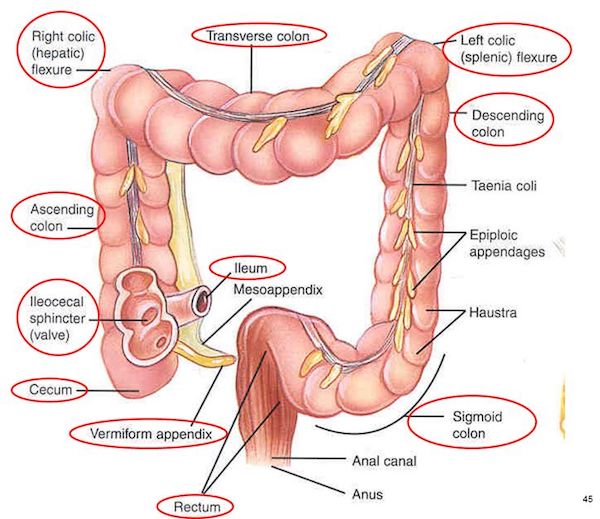

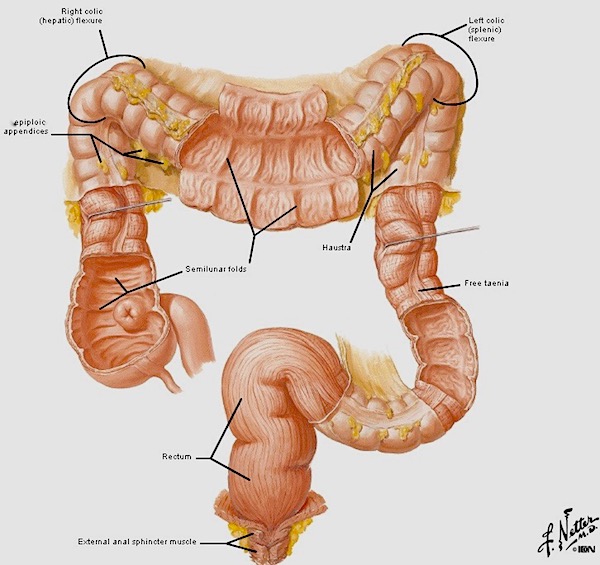

Other Features: Large intestine also exhibits three other important anatomical features (Image B):

- ileocecal valve – opening between ileum and cecum

- right colic (hepatic) flexure – near the right lobe of liver

- left colic (splenic) flexure – near spleen

Image B

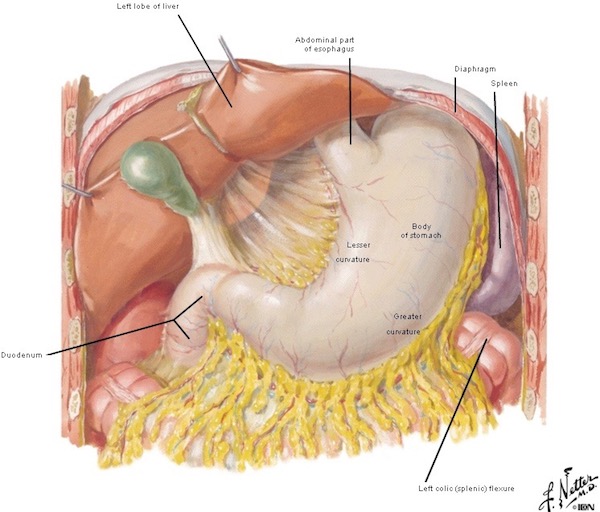

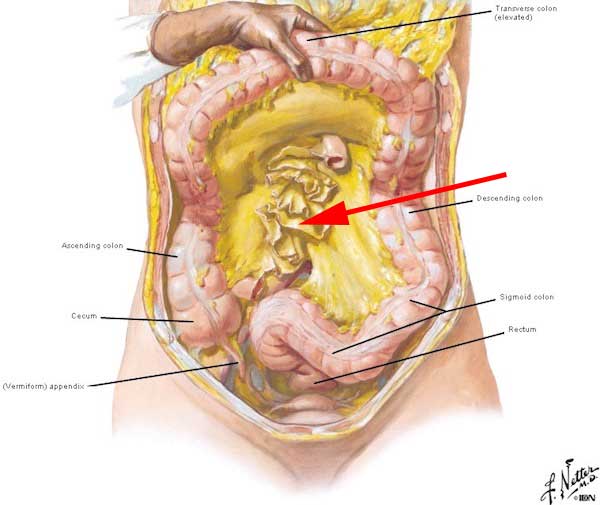

Location: Large intestine lies in the abdominal cavity partially covered by small intestine. Removing small intestine requires cutting the root of the mesentery (Image C – red arrow) – this mesentery suspends small intestine from the posterior abdominal wall (Anatomy Lesson #47, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!” – GI Tract, Part 4).

Now, lifting greater omentum and transverse colon reveals all parts of the large intestine, except anal canal (Image C). The mesentery (yellow in Image C) envelopes most of large intestine, securing the parts in their respective positions and containing blood and nerve supplies. Appendix, cecum, and ascending colon typically sit on the right side of the abdominal cavity – descending and sigmoid colons are on the left. Transverse colon hangs between right and left colic flexures. Rectum lies in the midline of the pelvic cavity.

Understand that exceptions to this arrangement do occur. One rare congenital condition, situs inversus totalis, happens once in every 10,000 people. Here, all abdominal and chest organs are flipped 180°. So, for example, appendix lies in lower- left abdominal cavity. Competent health practitioners must keep such rarities in mind while assessing patients.

Image C

Now, onto specific parts of large intestine.

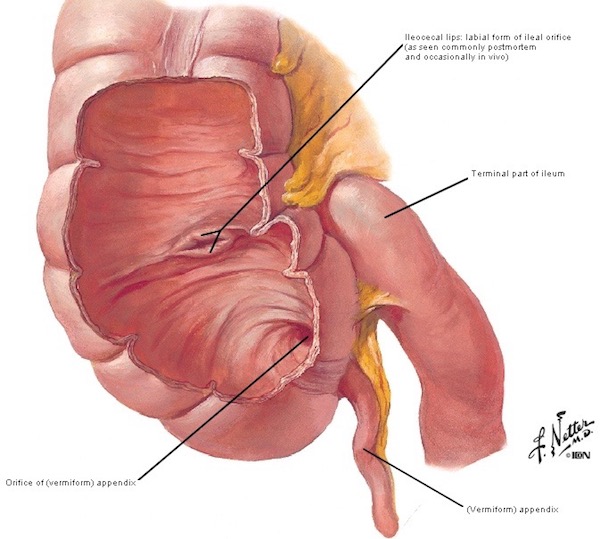

Cecum: The term, cecum or caecum (British spelling), comes from the Latin caecus, meaning blind: not as in sightless, but as in cul-de-sac. The cecum is an enlarged pouch typically located on the right side of the abdominal cavity and is the first part of large intestine. Both appendix and ileum open into the cecum (Image D).

Cecum and ileum are separated by an ileocecal valve, a slit-like opening in the cecal wall. The valve contains a sphincter of smooth muscle, opening to admit chyme from the ileum, and closing to prevent back flow. Thus, cecum serves as a receptacle for fluid chyme.

Image D

History Detour: Almost simultaneously, the ileocecal valve was described by Dutch physician, Nicholaes Tulp, and by Swiss botanist, Gaspar Bauhin. Depending on which scientist one intends to honor, the iliocecal valve is also either the Tulp valve or the Bauhin valve. Yep, the way the world works!

In case you forgot or haven’t read Anatomy Lesson #34, “The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy,“ Tulp is the anatomical demonstrator in Rembrandt’s 1632 painting (Image E), “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.” Several modern anatomists have performed dissections trying to recreate the left forearm tendons as depicted in the painting, but to no avail; the painting is anatomically incorrect, which matters ZIP because it is priceless!

Image E

Pretty cool, eh? Now, back to the lesson!

Vermiform Appendix: The appendix is more accurately termed vermiform appendix, cecal appendix, vermix, or vermiform process. Why use one name when four will do, hah! To improve student vocabulary? No, not really. Adding a second word provides specificity because the body has other appendices (pl.) including those associated with ovary, testis, and colon. Thus, vermiform helps verify which appendix is intended.

I prefer the term vermiform appendix. Why? Vermiform is from the Latin vermes meaning “worms” + formes meaning “shape.” Appendix refers to a process or projection. Voila! A normal vermiform appendix is shaped very much like a long, pink worm!

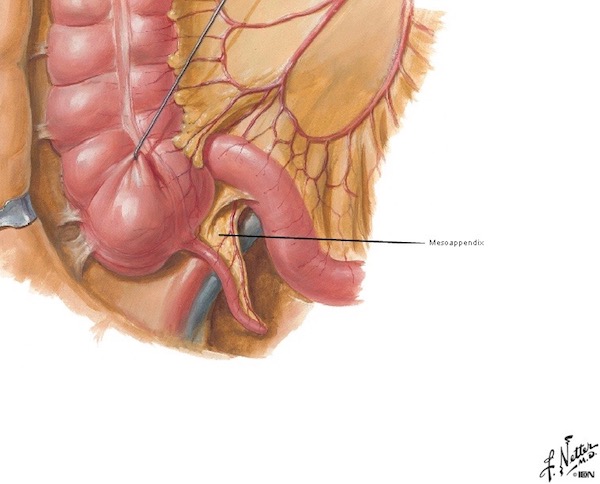

Enough with word roots. Vermiform appendix is a blind-ended, worm-like extension projecting from the cecum and usually located in the lower right abdomen (Image F). It is suspended by a mesoappendix, a fold of mesentery that also provides a conduit for blood vessels and autonomic nerves.

Image F

Appendiceal Location: Illustrations typically place vermiform appendix in the lower right abdominal position, as mentioned above. But, it may assume one of about eight positions relative to the cecum (Image G). Or, a cecum may ride high in the upper right abdominal cavity carrying the vermiform with it, or even shifted to the left side as in situs inversus (Image G). Vermiform appendix may also drift into an inguinal hernia (Image G – red arrow). Interestingly, some alternate appendiceal positions are more prevalent among some populations and cultural groups. Such positional variations can present confusing signs and symptoms and pose diagnostic challenges for practitioners. Truth!

Image G

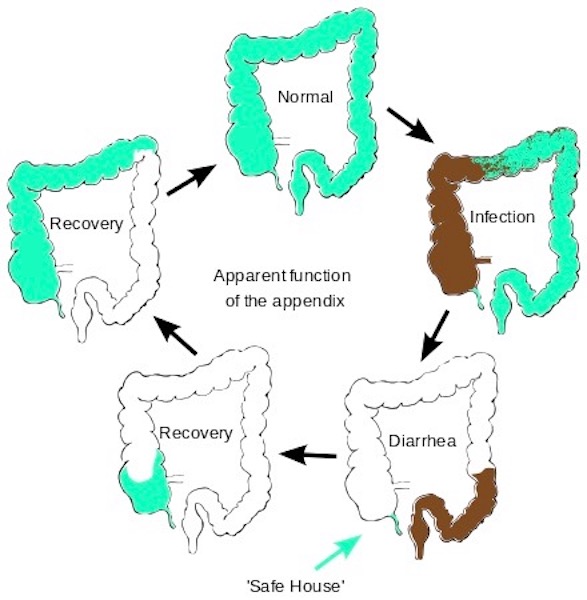

Function #1: The function of vermiform appendix is unclear. Many anatomists consider it a useless relic of an evolutionary past. But, recent studies suggest it acts as a reservoir for good bacteria. After severe diarrhea, the vermiform appendix apparently “reboots” the large intestine by repopulating it with normal bacterial flora (Image H).

I always taught, and still firmly believe, the body doesn’t have useless organs. I reason that if a body part appears useless, it is our own ignorance that impedes understanding. I must confess, though, one savvy student stumped me with the question: “why do men have nipples?” I had no answer then, but I do now – subject for another lesson. Understand, the half-life of medical facts is about 5 years, so new and/or revised info emerges daily! Stay tuned! Hee, hee.

Image H

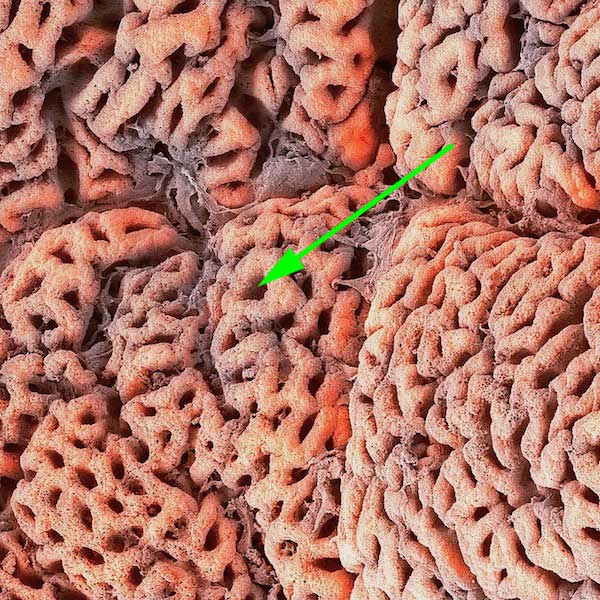

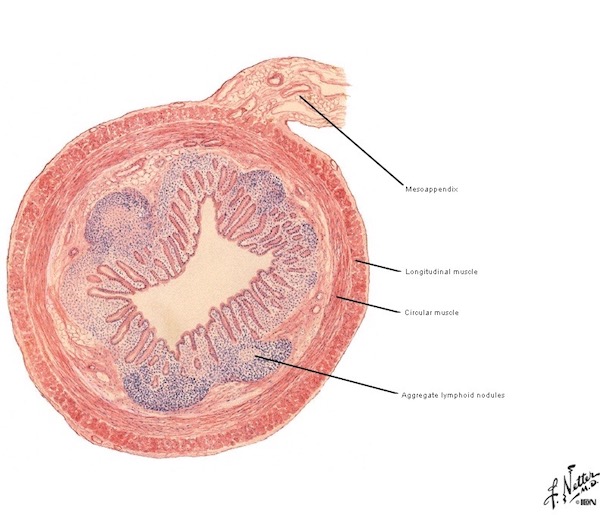

Function #2: Vermiform appendix also serves as a lymphoid organ. Remember the tonsils (Anatomy Lesson #45 “Tremendous Tube” – GI Tract, Part 2) and Peyer’s patches of ileum (Anatomy Lesson #47, “Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!” – GI Tract, Part 4)? Moving to a microscopic image, these are aggregates of lymphoid nodules (spheres) containing lymphocytes and other cells functioning in immune responses. Turns out the wall of vermiform appendix is loaded with lymphoid nodules (Image I – blue circles with pale centers) which constantly survey luminal proteins to determine which ones are threatening and require an immune response. Cross my heart!

Now, you may argue that vermiform appendix is of dubious value because many people survive without one. My response: well, people can also live without a leg but that doesn’t mean it isn’t useful! Aye?

Image I

Appendicitis: As we learned in Anatomy Lesson #37, “Outlander Owies Part 3 – Mars and Scars,” any anatomical word bearing the suffix “-itis” means inflammation of… Thus, appendicitis means inflammation of the appendix, a condition accompanied by swelling, redness, pain, heat, and loss of function.

Book Spoiler #1: The following quote is from Diana’ sixth big book, “A Breath of Snow and Ashes.” You might skip if you haven’t read it, although the quote doesn’t reveal any plot twists. How did prescient Diana know this lesson needed a quote about appendicitis? One of the great mysteries! <G>

The book describes Surgeon Claire treating a young boy with acute appendicitis. I borrow shamelessly from Starz episode 203, Useful Occupations and Deceptions, to illustrate the quote:

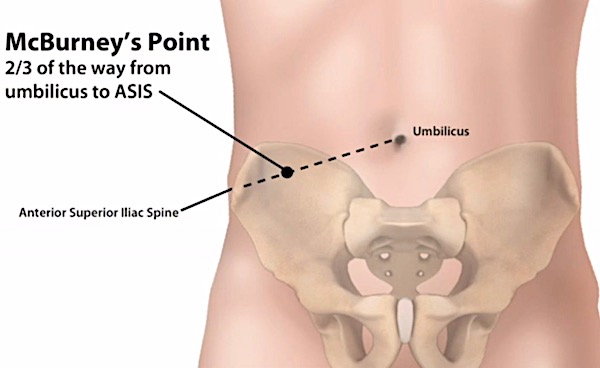

I put a thumb in his navel, my little finger on his right hipbone, and pressed his abdomen sharply with my middle finger, wondering for a second as I did so whether McBurney had yet discovered and named this diagnostic spot. Pain in McBurney’s Spot was a specific diagnostic symptom for acute appendicitis. I pressed Aidan’s stomach there, then I released the pressure, he screamed, arched up off the table, and doubled up like a jackknife. A hot appendix for sure. I’d known I’d encounter one sometime…. No doubt about it, and no choice; if the appendix wasn’t removed, it would rupture.

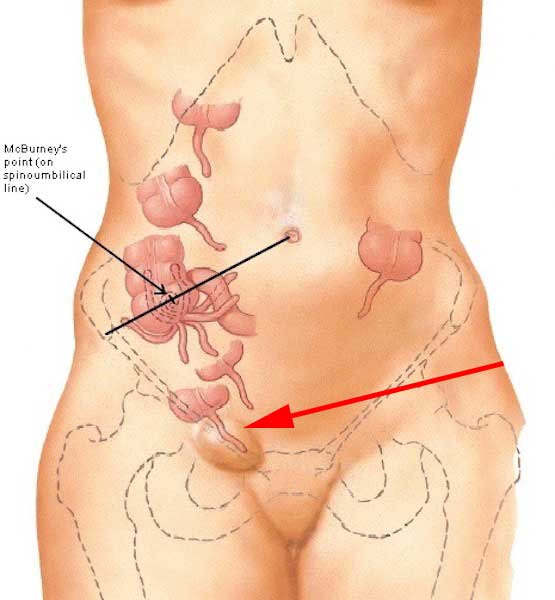

McBurney’s Point: Sounds like a feature of the Scottish coastline <g>, but, its not! McBurney’s Point is the name for a spot on right abdomen that is two-thirds the distance from umbilicus to ASIS, the anterior superior iliac spine of the right hip bone (Anatomy Lesson #39, Anatomy Lesson #39 “Dem Bones – Human Skeleton”). This point roughly corresponds to the most common site where appendix attaches to cecum (Image J). Warning: some descriptions define the point as one-third distance from ASIS to umbilicus. What gives? Going the opposite direction, the latter statement is also true. Do the math!

Try This: Stand before a mirror. Place right fingers over the most prominent bony knob of right hip bone. You know the one – it bumps into corners of tables? Ouch! Now, place right little finger on right ASIS. Place right thumb in navel. Estimate 2/3 distance from thumb to little finger or estimate 1/3 distance from little finger to thumb – this is McBurney’s point! If this is too tough, estimate the halfway point – it will be close. This is likely where the base of your vermiform appendix (if you still have one, of course!) attaches to cecum.

Image J

Back to Appendicitis: And in answer to Claire’s musing, no, McBurney’s point was not described in the 18th century. Who was McBurney? Charles McBurney was an American surgeon who, in 1889, published the relationship between acute appendicitis and McBurney’s point, the typical site of greatest tenderness. Understand, this relationship is not 100% reliable because of appendiceal positional variations and because other abdominal processes may produce tenderness at this site.

Nevertheless, McBurney’s point is significant in three ways:

- marks the most common site where appendix attaches to cecum.

- intense tenderness is consistent with acute appendicitis and possible progression toward rupture.

- most open appendectomies (not by laparoscopy) are performed at McBurney’s point.

Back to Dr. Claire and her spot-on description of anatomy and acute appendicitis!

“All right,” I said out loud, triumphant. “Got you!” Very carefully, I hooked a finger under the curve of the cecum and pulled a section of it up through the wound, the inflamed appendix sticking out from it like an angry fat worm, purple with inflammation. “Ligature.” I had it now. I could see the membrane down the side of the appendix and the blood vessels feeding it. Those had to be tied off first; then I could tie off the appendix itself and cut it away. Difficult only because of the small size, but no real problem … “Forceps.” I pulled the purse-string stitch tight, and taking the forceps, poked the tied-off stump of the appendix neatly up into the cecum. I pressed this firmly back into his belly and took a breath.

BTW, the membrane mentioned in the quote is the mesoappendix but you likely figured that out, already. Image K shows what Aiden’s appendix might have looked like after extraction (sans blue terrycloth).

Image K

Moving on…..

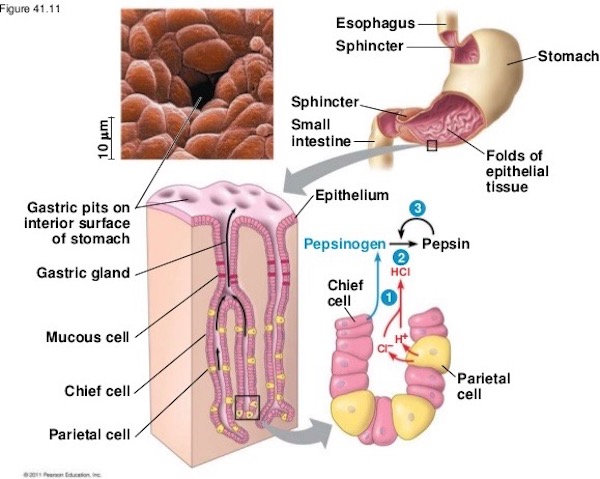

Ascending, Transverse and Descending Colons: Most of the length of large intestine is composed of ascending, transverse and descending colon. These parts can be distinguished easily from small intestine because their diameter is larger and they possess these unique features (Image L):

- epiploic appendices – fatty globs dangling from the outer surface of colon (even in thin folks)

- haustra – wall pouches giving the surface a saccular (sack-like) appearance

- taenia coli – meaning “worms of the colon”, these longitudinal bands of smooth muscle travel the length of the colon (think of them like purse stings holding the wall into haustra)

The mucosa (internal lining) of the colon has no villi, the finger-like extensions riddling the mucosa of small intestine. It does exhibit semilunar folds, transverse folds of mucosa that partially encircle the lumen to increase surface area and support stool (feces). The wall of the colon also contains smooth muscle layers which contract to move stool through the lumen.

Colon Functions:

- Absorbs water from luminal contents converting them into more solid stool.

- Saccular design accommodates luminal mass as it solidifies.

- Houses massive numbers of bacteria which breakdown food matter.

- Absorbs nutrients from digestion by colonic bacteria and leftovers from small intestine digestion.

- Releases mucus (protein with attached CHO groups) into the lumen making contents slippery.

Image L

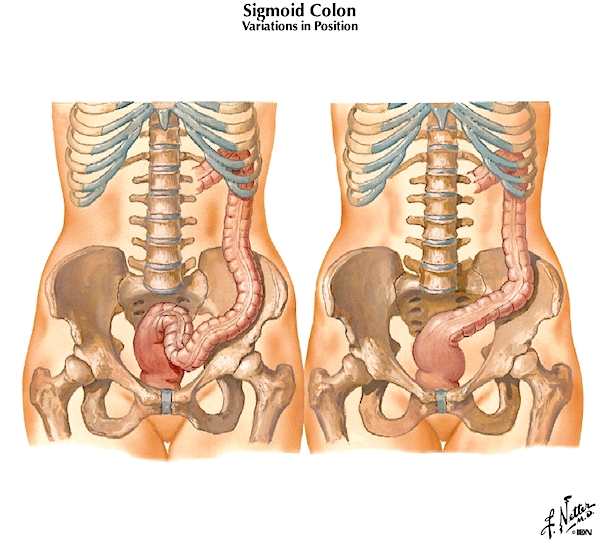

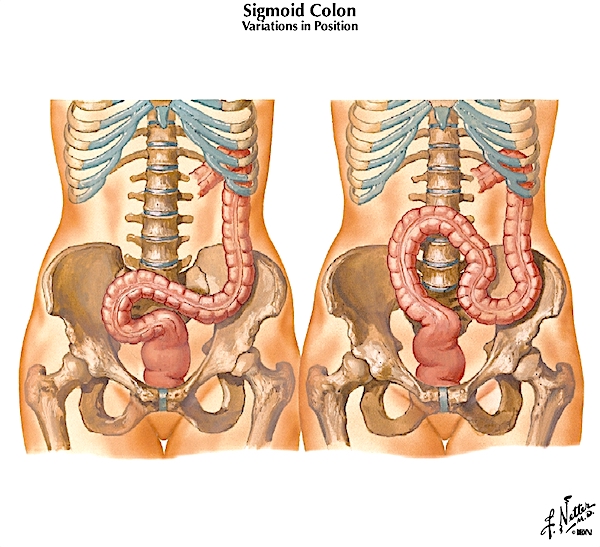

Sigmoid Colon: The sigmoid connects descending colon with rectum. Sigmoid is so named because it is generally S-shaped, although it varies considerably in shape and length! Some of variations are shown in the next two images. Left side of Image M shows a typical sigmoid; right side shows a short, straight sigmoid angling into the pelvis.

Image M

Left side of Image N shows a long sigmoid with a large loop shifted to the right; the right side of the image shows a long sigmoid ascending high into the abdomen. The point is, normal sigmoids assume different shapes, lengths, and positions.

The function of the sigmoid is to accumulate fecal waste until it is ready to leave the body.

This reminds me of a fav saying by surgeons I have worked with: “The good news: there is a light at the end of the tunnel. The bad news: it is a sigmoidoscope!”

Image N

Heeeeeere’s Jamie (Image O) to give you a wee bit of warning! Next up are rectum and anal canal. If these topics cause you discomfort, skip to Jamie and Claire laughing, just before the pelvic floor!

Image O

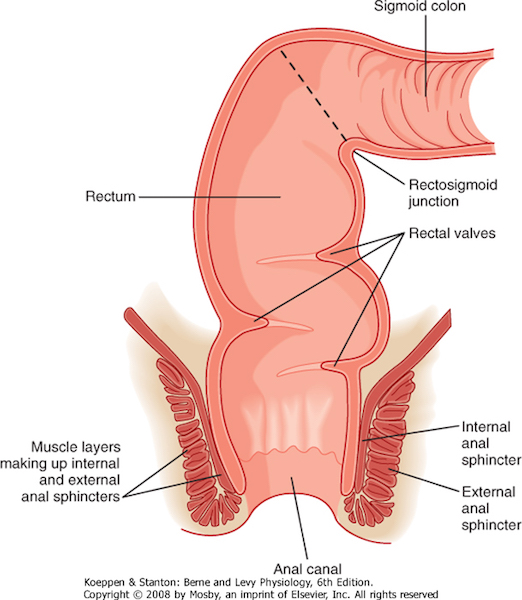

Rectum: The next organ is rectum, the segment between sigmoid colon and anal canal. At its start, the diameters of sigmoid and rectum are the same, but rectum enlarges as it descends into the pelvis (Image P). Many sources define rectum as extending all the way to the anus, but this is not so; rectum converts to anal canal as it passes through the pelvic floor (Image P – black arrow) and anal canal, being a separate part, ends at the anus.

Rectum has no taenia coli or epiploic appendices and it lies in the pelvic cavity, making it easily distinguished from sigmoid. Otherwise, its wall contains smooth muscle and a mucosal lining very much like the rest of large intestine.

The rectum serves as a storage receptacle for feces awaiting release via the anal canal. Rectal valves (Image P) are folds of mucosa that help support stool. During elimination, smooth muscle of the rectal wall contracts to aid defecation. And, rectum releases loads of mucus to aid the movement of stool.

Image P

Och! Here is public proof that many mistakenly believe the rectum reaches all the way to the anus; the so-called rectum bar in Vienna (Image Q) is anatomically incorrect. Who on god’s green earth considered this a viable idea? Would you sample refreshment from such an edifice? Snort!

Image Q

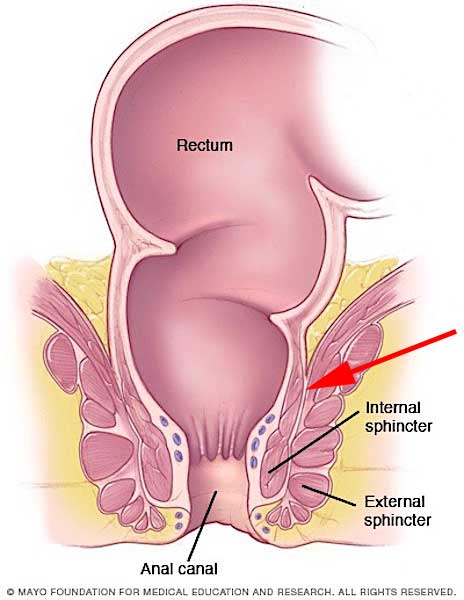

Anal Canal: Last stop! The final segment of large intestine is anal canal (Image R). This complicated structure is pretty short, being only about 1” – 1.5” in length. It begins as rectum traverses the pelvic floor (see below) and ends at the anal verge (anal opening). Its orientation is not vertical, as it is directed downward and backward.

Anal canal is lined with mucosa turning to skin near the anal verge. Its wall contains an internal anal sphincter, smooth muscle over which we exert no voluntary control. Outside the internal sphincter is a sturdy layer of skeletal muscle forming an external anal sphincter, which is controlled voluntarily. Yay!

Normally, both sphincters are tonically contracted but relax during elimination. Psst….a child learns to control the external sphincter during potty training. In most children, this cannot occur until about 18 months due to nerve immaturity. A younger child can be taught to alert the parent when defecation is eminent, but he/she cannot voluntarily control the process.

Image R

Here they are, the cuties! Everybody make it through as far as the pelvic floor?

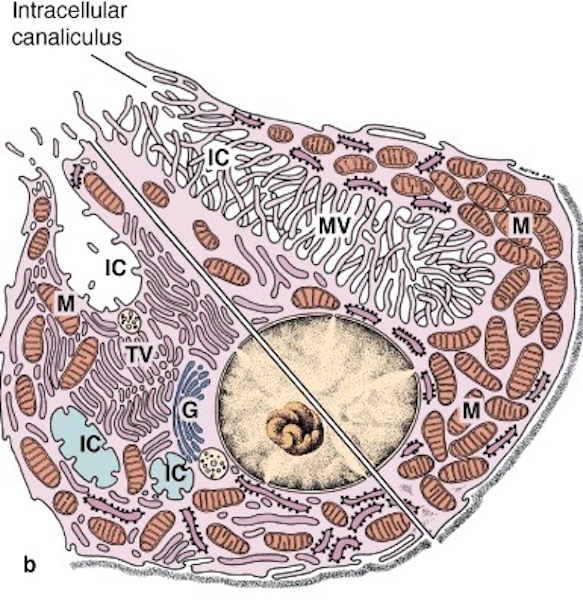

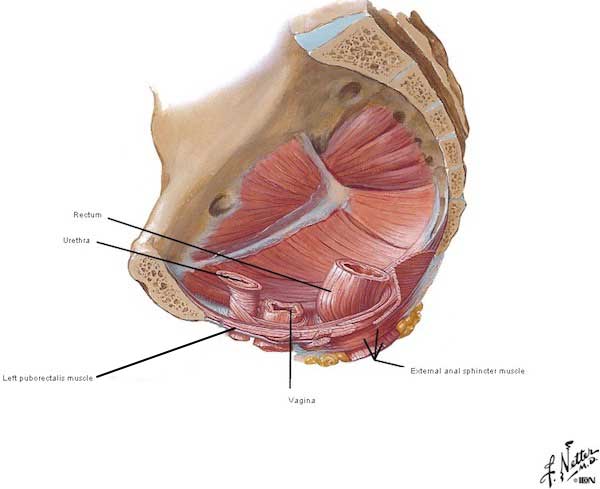

Pelvic Floor: Although not part of large intestine, we must discuss this area because fecal (and urinary) continence requires a healthy pelvic floor. The pelvic floor is formed by the fusion of right and left levator ani muscles forming a muscular diaphragm (we have more than one) that hangs from the bony pelvis much like a hammock (Image S). The floor is pierced by two midline openings in the male, one for urethra and one for anal canal. The female has three midline openings, two the same as a male, plus a middle opening for the vagina (Image S). Each of these openings is supported by levator ani muscles. Although the pelvic floor appears spacious in Image S, in reality it is about the size of half a grapefruit. Very tight squeeze, indeed!

The Way Things Work: A subpart of each levator ani, the puborectalis muscle (Image S) passes backward from each pubic bone to fuse behind the rectum. Forward pull by these paired muscles creates a flexure causing the anal canal to drop downwards and backwards, and thereby closing the channel between rectum and anal canal. During elimination, puborectalis muscles, internal anal sphincter, and external sphincter relax allowing the passage of stool; otherwise, all of these muscles normally remain contracted.

Image S

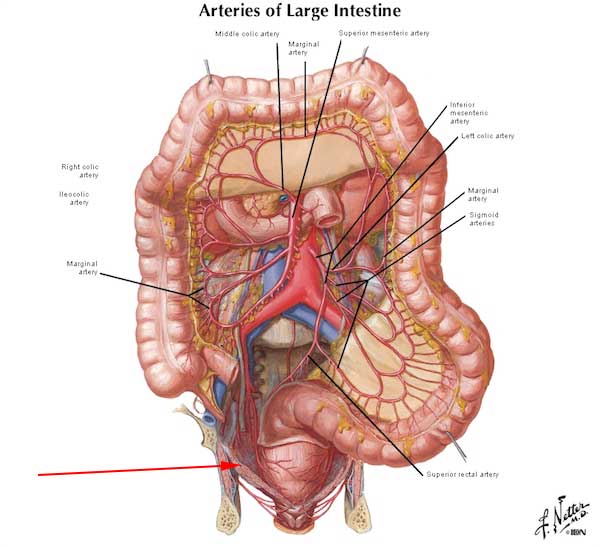

Blood Supply: Like small intestine, large intestine requires a huge blood supply (Image T). Arteries arise from the aorta and its branches supplying all parts of large intestine, from appendix through anal canal. Major arteries also join to form a marginal artery that follows the contour of the large bowel (Image T). Veins follow similar routes.

This prolific blood supply is used for transport of absorbed nutrients, but also provides a huge oxygen supply because bowels are excruciatingly sensitive to oxygen loss. This is why a twisted bowel, bowel loop caught (incarcerated) in a hernia, or other bowel obstruction is of high concern as such events rob bowels of their blood supply and the accompanying cargo of oxygen – these conditions present a medical emergency which must be quickly addressed to avoid bowel death! And, yes, bowel obstructions occur in both large and small intestines. BTW, the red arrow of Image T points to the pelvic floor separating rectum from anal canal.

Book Spoiler #2: From Diana’s third book, Voyager, we read about a patient with a strangulated bowel, caught in a hernia. Too late, the bowel is dead, and Claire is none too happy about it. Again, this quote contains no plot twists, so it might be safe for you to read.

The cause of death was more than obvious: a strangulated hernia. The loop of twisted, gangrenous bowel protruded from one side of the belly, the stretched skin over it already tinged with green, though the body itself was still nearly as warm as life. An expression of agony was fixed on the broad features, and the limbs were still contorted, giving an unfortunately accurate witness to just what sort of death it had been. “Why did you wait?”

Image T

Book Quote: Now, let’s apply some of knowledge gleaned from this lesson. Diana’s second big book, Dragonfly in Amber, describes a horrifying scene wherein Mr. Forez describes to Jamie, the disembowelment of criminals! He hopes to dissuade Big Red from engaging in various occupations and deceptions, no matter how useful. As this scene wasn’t included in the Starz episodes, I’ve used a substitute image of the King’s hangman at L’Hôpital des Anges (Starz episode 204, La Dame Blanche)!

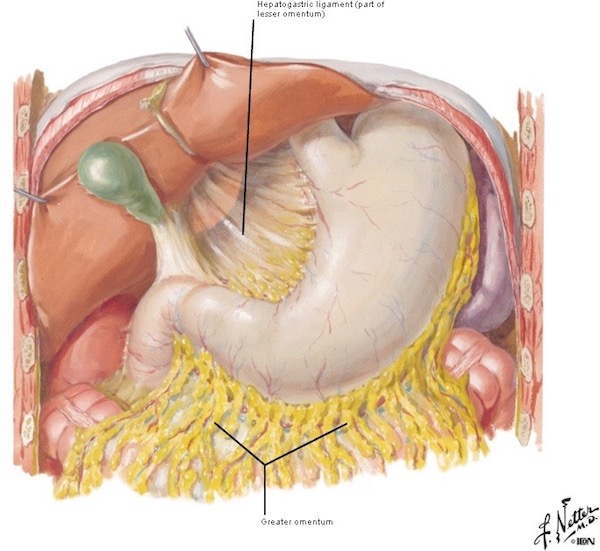

“Just there,” he said, almost dreamily. “At the base of the breastbone. And quickly, to the crest of the groin… —and the letter opener flashed to one side and then the other, quick and delicate as the zigzag flight of a hummingbird—“following the arch of the ribs. You must not cut deeply, for you do not wish to puncture the sac which encloses the entrails. Still, you must get through skin, fat, and muscle, and do it with one stroke. This,” he said with satisfaction… “is artistry.” .. “After that, it is a matter of speed and some dexterity, but if you have been exact in your methods, it will present little difficulty. The entrails are sealed within a membrane, you see, resembling a bag. If you have not severed this by accident, it is a simple matter, needing only a little strength, to force your hands beneath the muscular layer and pull free the entire mass. A quick cut at stomach and anus”—he glanced disparagingly at the letter opener—“and then the entrails may be thrown upon the fire.

Mr. Forez’s description of disembowelment has a few anatomical problems. Scout’s honor. Here’s why:

- The sac (peritoneum) sealing the entrails also hugs the body wall; once a knife pierces the body wall, too late, that sac has already been severed.

- Severing skin, fat, muscle and peritoneum in one stroke is nigh to impossible, waaaay too tough! Sawing, maybe!

- There isn’t a muscle layer under the bag of entrails.

- A quick cut at stomach isn’t possible as it is covered by greater omentum and transverse colon and tethered by membraneous ligaments. Cannot be reach quickly or severed easily.

- A quick cut at anus is even less likely because it lies below the pelvic floor – this tough fibro-muscular layer is very hard to access and dissect in such a confined space!

- If the gut from stomach through anus were removed, the victim would immediately go into shock and rapidly exsanguinate from the severed blood vessels.

Truth: Evisceration was designed to keep a convict alive long enough to ensure maximum suffering! So, typically, a short segment of small bowel was pulled through a belly incision, cut out, and thrown on the fire or given to dogs to eat. Thus, the still living victim could gaze with horror at the fate of his own entrails before finally going into shock from blood loss. Vicious prospect. Who thought this one up????

My conclusion for the boo-boos in Mr. Forez’s gory tale is that first, he is not an anatomist, and, second, he deliberately embellished his gruesome story with horrific inaccuracies to halt Jamie’s seditious activities. Of course, this threat didn’t work! Jamie is one stubborn Scot, aye?

So, we now know the structure and functions of the large intestine. Let’s take a few moments to discuss what happens inside the dark tube.

Good Bacteria: We generally think of bacteria as being bad, but in a normal gut, most are good (Image U). Although stomach and small intestine contain relative few species of bacteria, numbers in the large intestine are staggering! More than 1,000 different species of bacteria inhabit the normal large intestine, collectively, that’s trillions of bacteria! Here’s an astonishing factoid: dried feces is 60% bacteria. Yowser!

Image U

Microbiota: Gut flora, collectively known as the microbiota, is a complex community of organisms living mostly in large intestine. Interestingly, our gut flora is established by one to two years of age. Because the gut and its bacteria co-developed, our gut becomes tolerant to, and even supportive of, gut flora. These organisms aren’t just commensal, they are mutualistic, meaning both they and we benefit. Here is what they do for us:

- Ferment dietary fiber (cellulose) into molecules which we can absorb.

- Synthesize Vitamins B and K.

- Probably act as an endocrine organ.

- May protect against inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

- Fill ecological niches that that might otherwise be subject to hostile takeover by pathogenic organisms.

Image V presents a marvelous visual of gut bacteria, a scanning electron micrograph (SEM). It would be great fun if gut bacteria really did come in such marvelous colors, but, no, these are computer generated. The woody-looking slab isn’t for the fireplace; it is a wee shard of dietary fiber!

Image V, SEM by Martin Oeggerli

Western Diet: Now, we could get embroiled in a messy discussion about diet as there is a gut-full of claims floating around in the ethernet. I don’t mean to be a harpist about the western diet (Image W), but 90% of Americans do not know there is a link between diet and cancer!

To the point: Colorectal cancer (bowel cancer) is the second highest cause of cancer deaths, both in the US and in Great Britain! Americans are 13 times more likely to develop bowel cancer than Africans. Thus, in a recent scholarly study, 30 healthy Africans were fed an American diet (high fat, low fiber) and 30 Americans ate an African diet (high fiber, low fat). After two weeks, two weeks I say!, all subjects received a colonoscopy and various tests. Americans on the African diet experienced decreased inflammation and increased production of a fatty acid proven to protect against colon cancer. Africans on the American diet showed increased inflammation and changes that precede the development of cancerous colon cells. This short term study underscores the speed with which an adverse relationship between poor diet and poor colonic health may develop.

Hopefully, you all realize that dietary fiber (roughage) is needed for the large intestine to do it’s job (hee, hee). Fiber helps prevent “traffic jams!” Eating lots of whole grains, legumes, fruits, and veggies aids elimination. Too little dietary fiber coupled with too much fat is a fine recipe for “road blocks!”

Image W

Now, time for some potty talk! Outlander provides, as always…Yep, Diana’s books contain a number of references to beautiful bowels and their dubious duties (Dragonfly in Amber book).

“A verra wearisome business it was, too,” he added, bending over and setting his hands on the floor to stretch the muscles of his legs.

What is wearisome, and whom is Jamie discussing? Why, King Louis of France, of course (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore). Annalise de Marillac does Jamie the dubious honor of hustling him off to observe King Louis perform his morning “rituals” – Murtagh follows, at Claire’s command! The puir man must poop before the entire world. Imagine!

Prof. Jamie explains further in Dragonfly in Amber book:

Took forever; the man’s tight as an owl.” “Tight as an owl?” I asked, amused at the simile. “Constipated, do you mean?” “Aye, costive. And no wonder, the things they eat at Court,” he added censoriously, stretching backward. “Terrible diet, all cream and butter. He should eat parritch every morning for breakfast—that’d take care of it. Verra good for the bowels, ye ken.

This puir King was famously costive because his fat-rich/low-fiber diet resulted in chronic constipation. And, constant straining can balloon the walls of veins draining the anal canal, resulting in hemorrhoids (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore). Truth be told, Lionel Lingelser is one fearless thespian! Hope he was well-paid for this scene; check out the rivulets of sweat streaking his forehead. Oooooh, straining!

Our two “gently-bred” Scots are frankly appalled but they observe the theatrics with manly composure leading Jamie to prescribe peasant parritch for breakfast each morn (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore)!

Who do you think has the worst job? King Louis who must master his bowels before the known universe, or the court physician who must verify his success – or lack thereof (Starz episode 202, Not in Scotland Anymore)? Hard to say, hah!

Thus “ends” the saga of the GI Tract from lips through anus – it took 5 lessons to cover this tremendous tube!

Let’s close this lesson with a few jokes about large intestine and its duties…. dumb but not too offensive, I hope!

- Have you seen that new movie, Constipated? … It’s not come out yet!

- Have you seen its sequel, Diarrhea? … It leaked, so they had to release it early!

- Did you know that diarrhea is hereditary? … It runs in your genes!

- I ate four cans of alphabet soup yesterday. Then I had the biggest vowel movement ever!

- People who tell you that they are constipated are full of crap. <G>

The body is sooo cool! Thus ends the fascinating tale of our large intestine, “The big Guy!” Next lesson, liver and its cohorts!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Karmen L. Schmidt, Ph.D.

PIcture creds: Starz, Atlas of Human Anatomy, Frank H. Netter, M.D., 4th ed. (Images C, D, E, F, G, I, L, M, N, S, T), Medicine Perspectives in History and Art, Robert E. Greenspan, M.D., 2006 (Image E), www.care2.com (Image O), www.enwiki.org (Image H; Image S), www.findchart.com (Image B). www.icanrunaminute.com (Image J), www.lydiaskindfoods.com (Image W), www.mayoclinic.org (Image R), www.medicalnewstoday.com (Image A), www.motherjones.com (Image U), www.ngm.nationalgeographic.com (Image V), www.researchgate.net (Image K), www.sites.google.com (Image P), www.walyou.com (image Q)