Hallo, anatomy students! Welcome to Anatomy Lesson #49, Our Liver – The Life giver. We finished our exploration of the GI tract proper (lips through anus), and today, we continue with associated organs of the GI tract. In former lessons, we learned that during embryonic development, various organs arise as outgrowths of the gut tube (Anatomy Lesson # 44, “Terrific Tunnel – GI Tract I”). Such organs retain these connections throughout life, so their products flow via ducts (tubes) into the GI tract proper.

Liver is on our docket today. Liver develops during intrauterine life as an outgrowth of the nascent gut, retaining its attachment via a system of hepatic ducts. And, as the title correctly states, liver is a “giver,” not a “taker.” Liver is the type of “anatomical“ personality we crave in our lives, as it is the seat of many life processes!

As always, this lesson sports Outlander images and quotes about liver. What? Are there really liver quote from our fav books and TV series? Indeed, there are!

Word Origin: Liver, is an Anglo-Saxon word (1325) for liv-er or lifer. Logically, the etymology for liver infers “life,” although the original intent is lost. The name is apt, though, because many vital life functions occur therein. And, our very busy liver has insinuated itself into history, prophecy, character, culture, horror, mythology, and medicine!

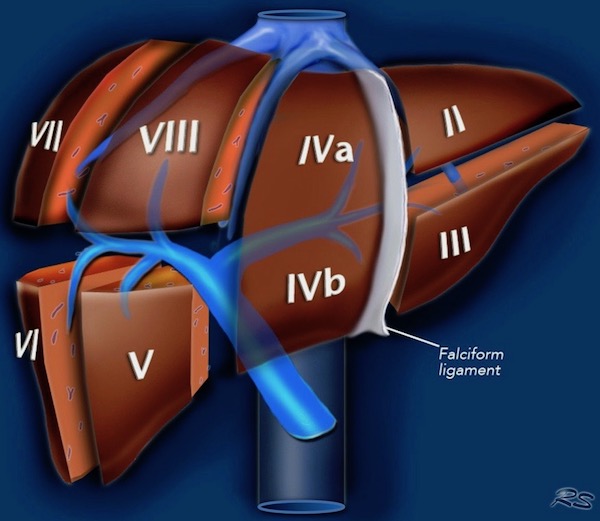

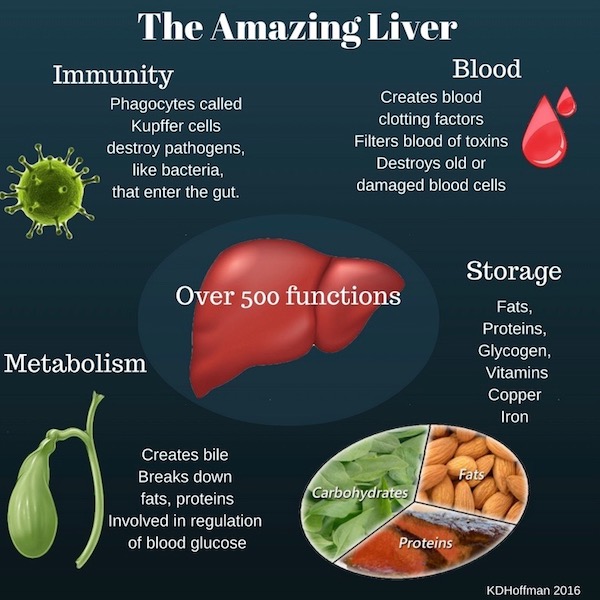

History: Greek physician, Claudius Galen (130-200 CE), anointed liver as the principle organ of the body, teaching it as the primary source of blood and lymph (Anatomy Lesson #34, The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy) – a status enjoyed for 1500 years! After this was disproven, liver fell from grace (sad face), only to have its stature revived in the 19th century by French physiologist, Claude Bernard. Bernard showed the liver serves many vital functions; indeed, we now know of at least 50 ways (TY, Paul Simon), to “love your liver” (Image A). But, counting all known liver functions, its duties approach 500!

Image A

Prophecy: Ever thought of a liver as a crystal ball? Believe it or not, livers were used for divination. Ancient Babylonians (19th century B.C.) studied sheep livers as a means to foresee the future. Such findings were documented on clay tablets in the shape of a sheep’s liver, complete with surface markings used for prophesying and instruction (Image B).

Image B

Character: The liver has the dubious honor of being used to symbolize a number of less savory human attributes, such as:

- lily-livered (cowardice)

- chopped liver (worthless)

- white liver (cowardice)

- hard liver (sensualist)

- liver-hearted (craven)

- liver-faced (mean-spirited)

- liver-lipped (pale and feeble)

- liver-sick (dropsy = cirrhosis or hepatitis)

Our beloved Outlander provides stellar examples of several such liver characteristics:

That lily-livered (coward), dastardly Duke (Starz, episode 110, By the Pricking of My Thumbs) peeks from behind a tree, leaving Jamie to battle three grumpy MacDonalds! Mayhap they only got haggis for brekky?

I think that I shall never see,

A more cowardly knave behind a tree!

From the same Outlander episode (Starz, episode 110, By the Pricking of My Thumbs), liver-faced (mean-spirited) Laoghaire spies Claire being arrested for witchcraft. She will happily sling the Heiland fling on Claire’s still-warm ashes!

I think that I shall never see,

A more wicked lass brimming with glee!

Now, please dinna fash, I affront the character, not the gifted and beautiful actress!

And before we leave Character-Assassination by liver, consider the hard-livered (sensualist), Black-Jack. A sociopathic-psychotic-sensualist if ever I saw one (Starz, episode 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul)!

I think that I shall never see,

A more depraved voluptuary than HE!

Culture: Many cultures offer idioms about the liver. This “pointed” one is an ancient Tibetan Proverb: My enemy’s liver is the sheath of my sword!

Och! Jamie and his men present a perfect metaphor for this dire warning, with raised blades at the Battle of Prestonpans (Starz episode 210, Prestonpans). Redcoat livers: take care and beware – your livers willna be living long!

I think that I shall never see

a more deadly blade than…Owie!

Horror: The liver appears in a surprising number of “settings and upsettings” to convey horror! Jonathan Demme’s 1991 horror film, The Silence of the Lambs offers a perfect example:

Check out this link to YouTube for a peek at this creepy scene!

Liver, fava beans, and a nice Chianti? Yuck. Well, maybe the nice Chianti. Hilarious Hannibal – the life of the party!

Mythology: Let’s not forget myths! Liver was immortalized in Theogony, a poem by Hesiod (8th – 7th century BCE), wherein the fate of the Titan, Prometheus (no relation to Ridley Scott), is recorded. Much to Zeus’s fury, Prometheus unwisely granted humans the gift of fire and the skill of metalworking. Zeus was so pissed, he chained Prometheus to a mountain rock. Immortalized in this stark painting (Image C), each day, Zeus sent an eagle to eat Prometheus’ liver and every night, his liver regenerated only to be devoured the next day. Eternal retribution (Prometheus eventually escapes)! Lesson learned: Yo mama always said, “dinna play with fire!”

Image C by Ruben and Snyders

Medicine: Many cultures have used liver as medicaments. Even today, cod liver oil is taken to lower high triglycerides and high blood pressure, and to treat some symptoms of diabetic-related kidney disease (www.webmd.com).

An 1899 book titled “Animal Simples,” by W. T. Fernie, M.D., states:

Dr. Heffinger advocates the taking of crocodile liver oil for phthisis; which almost supersedes the use of cod-liver oil in Peru; being more nourishing and palatable.

I dinna ken Dr. Heffinger, but I assume and presume he was a renown practitioner of 19th century medical arts. Oh, and phthisis is an old term for pulmonary tuberculosis, although liver oil likely had zero effect on this diabolical disease.

We encounter crocodile oil at Master Raymond’s Paris apothecary shop (Starz, episode 204 La Dame Blanche)! This “little shop of horrors” (snort!) displays pretty much every oddity in gay Paree! There’s even a quote from Dragonfly in Amber book:

“My crocodile ? Oh, to be sure, madonna. Gives the customers confidence.” He jerked his head toward the shelf that ran along the wall just above eye height… Three of the jars closest to me were labeled in Latin, which I translated with some difficulty—crocodile’s blood, and the liver and bile of the same beast, presumably the one swinging sinisterly overhead in the draft from the main shop

“never smile at a crocodile…..”

Gross Anatomy: OK, enough socializing – time for gross anatomy. Yay! Here, gross means visible with the naked eye (Anatomy Lesson #34, The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy); it does not mean yucky!

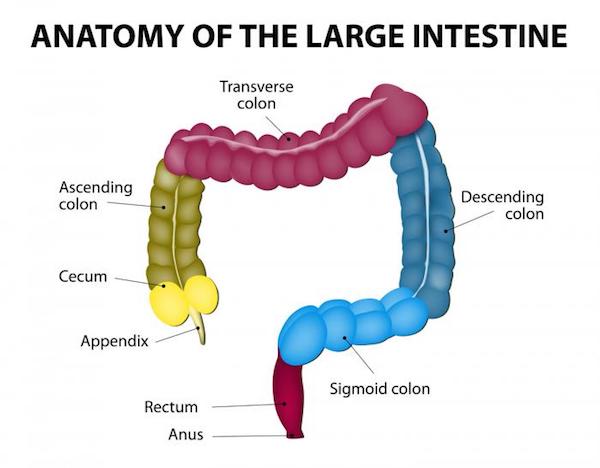

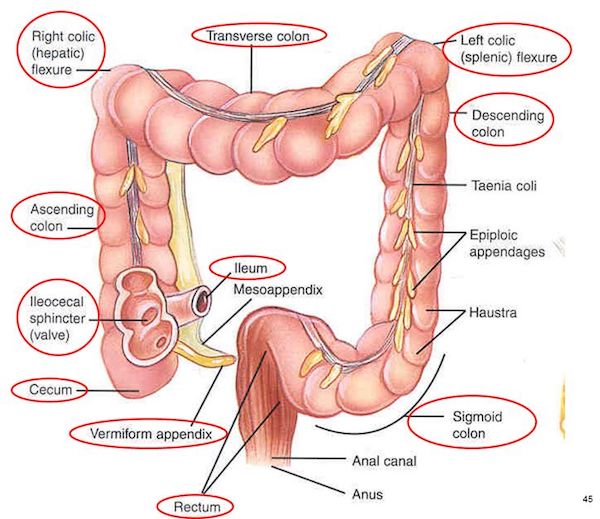

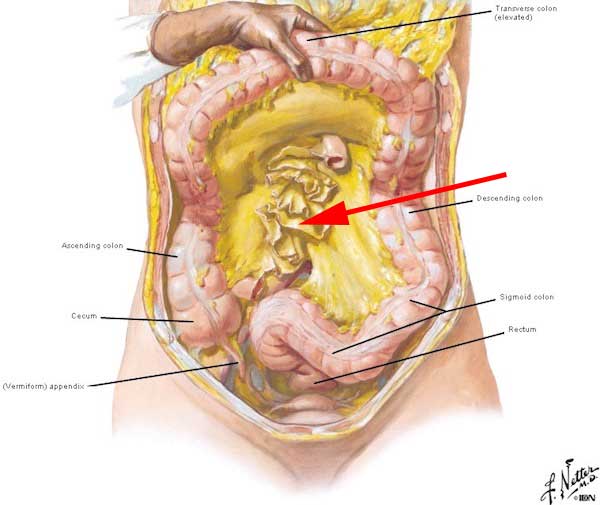

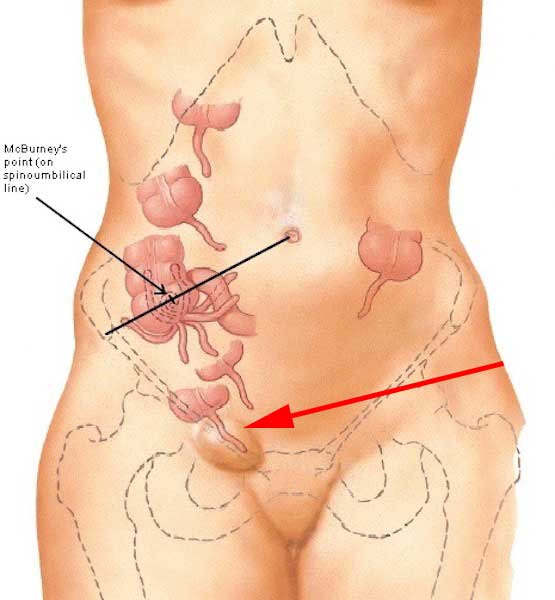

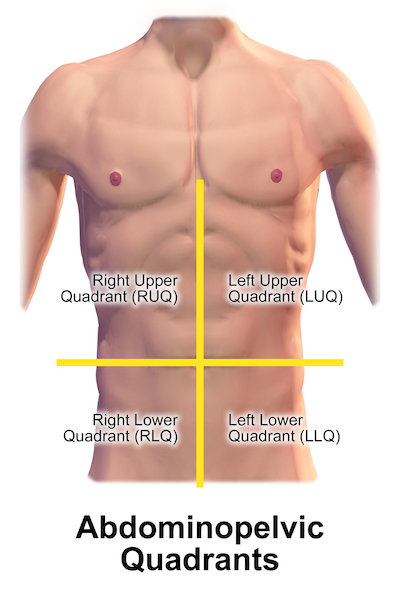

Location: Where, oh where, does the liver dwell? It lives in the abdominal cavity along with most of the GI tract. Its location is best defined by dividing the abdominal wall/cavity into imaginary quadrants (Image D); vertical and horizontal lines intersect at the umbilicus (Anatomy Lesson #16, Jamie’s Belly or Scottish Six-Pack), dividing the area into RUQ, LUQ, RLQ, and LLQ.

Most of the liver resides in the RUQ although some extends into the LUQ. There’s another anatomical method dividing abdominal cavity and wall into 9 segments but the quadrant system works best for today.

Image D

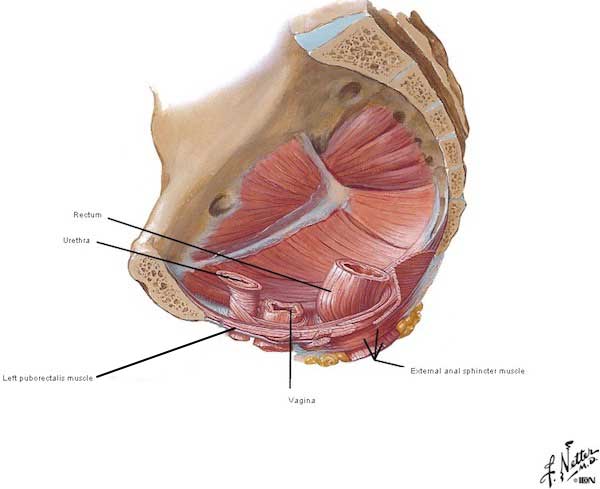

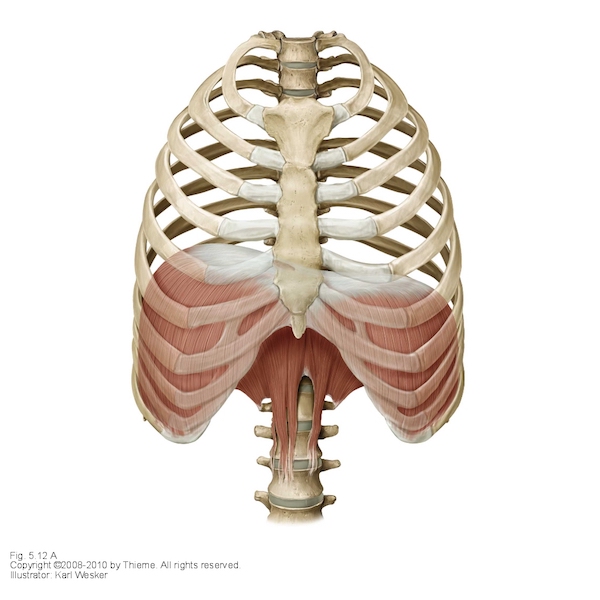

Respiratory Diaphragm: What does respiratory diaphragm have to do with liver? Lots! Anatomy Lesson #15, Crouching Grants – Hidden Dagger, taught that the respiratory diaphragm is parachute-shaped, doming upwards such that it is largely surrounded by rib cage, sternum, and vertebrae (Image E).

Image E

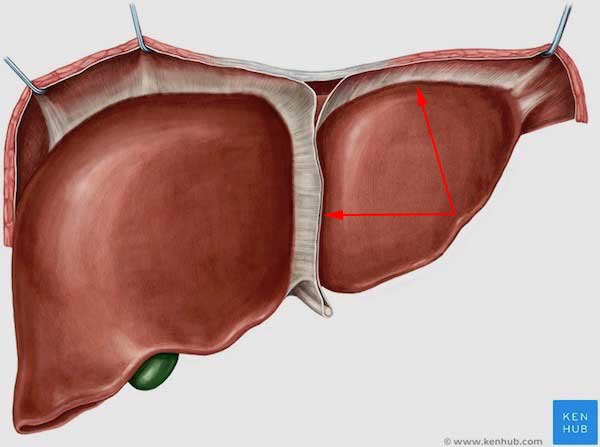

Anchorage: Liver abuts the respiratory diaphragm (Image F – hooks) but it doesn’t flop around in the RUQ. Rather, it is anchored in place by membranes (Image F – red arrows), layers of peritoneum which bind liver tightly to the diaphragm.

Image F liver

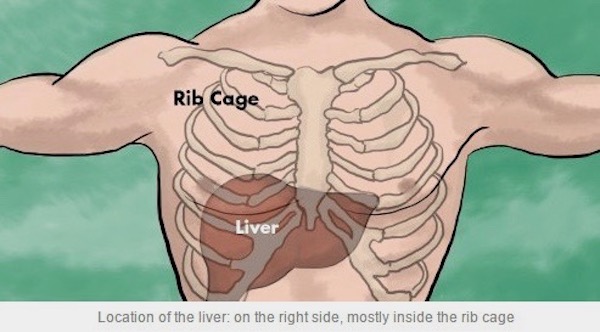

Ribs and Sternum: Because the liver abuts the respiratory diaphragm, it too, enjoys the immediate and privileged protection of sternum, ribs and vertebrae (Image G). As such, a normal liver is challenging for a practitioner to palpate. To do so, a patient lies on the back and inspires deeply; the practitioner presses fingers under the right costal margin and, if skilled, may be able to feel the margin of the liver slip under the fingers. Normal liver is soft, smooth and slightly tender to palpation. An easily palpated liver is usually associated with one of several issues, the most dire being hepatitis or neoplasia (tumor).

Image G

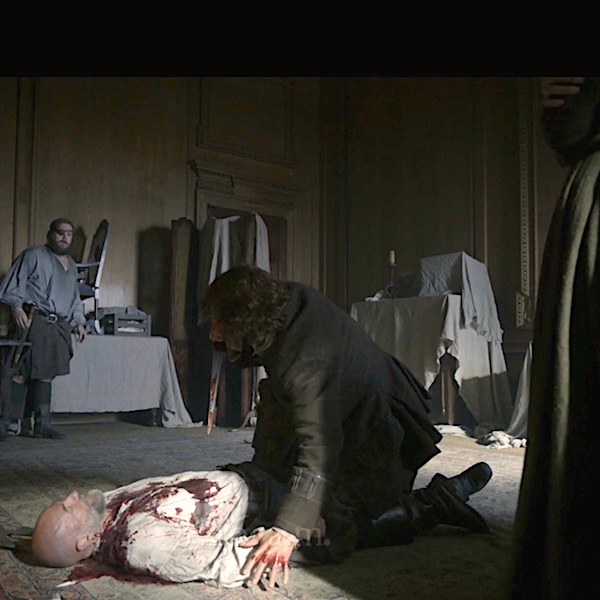

Forensics: It’s Outlander Time. Yay! Ever wonder where Dougal met his Demise-by-Dirk (Starz, episode 213, Dragonfly in Amber)? No, not in the attic! I mean, where was he stabbed? Did you think Claire and Jamie got him in the heart? Or, mayhap a lung? Forensic caps on!

Most likely, Dougal was stabbed in the liver! Yep. If ye look carefully, his wound is to the right of midline and above the costal margin. This means the dirk likely entered his RUQ, penetrating the right dome of respiratory diaphragm and piercing the right side of liver (Starz, episode 213, Dragonfly in Amber). No, Rupert, Jamie didn’t do the deed; or rather he didn’t do it alone! It took four hands to finish Dougal off by Dirk-Deed! Dougal, man, we miss your sass!

As the heart lies mostly to the left of midline and right lower lung is to the right of the wound, neither of these organs were likely pierced. Good job, anatomy sleuths!

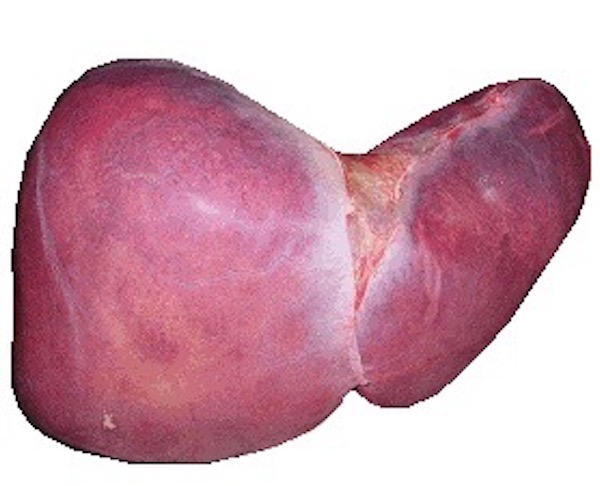

Physical Attributes: The adult liver is wedge-shaped, dense, and meaty, weighing 3-3.5 lb. Liver is our largest internal organ and the largest gland of the body, superseded in size only by our body’s largest organ, the skin (Anatomy Lesson #5, Claire’s Skin – Opals, Ivory and White Velvet). Ken the difference? Bonny!

Liver is solid in texture and deep red-purple-brown in color (Image H). Although liver mass constitutes only 2.5% of total body weight, the liver receives a whopping 25% of the cardiac output. Two and one-half pints of blood flow through a normal liver every minute of our lives!

Image H

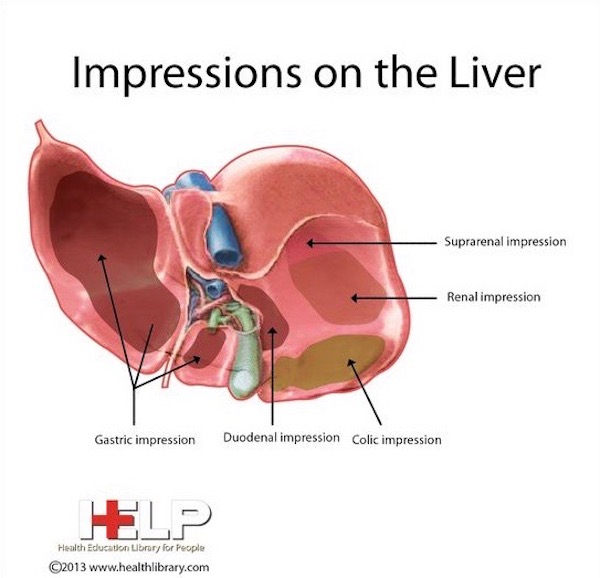

Impressions: Front, back, and top surfaces of liver are relatively smooth; flip liver up-side-down, and its under-belly bears ridges and valleys. The depressions, named impressions, are created by contact with adjacent organs including stomach (gastric), duodenum, adrenal (suprarenal) gland, kidney (renal), and colon (Image I). Gallbladder also leaves an impression, but this is visible only after its removal. Ergo, liver is centrally-located in the upper abdominal cavity with many important organ contacts.

Image I

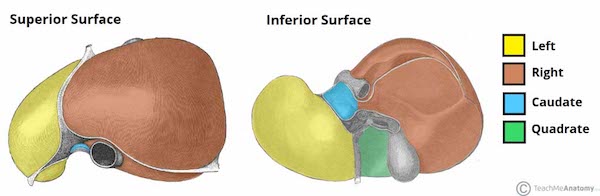

Anatomical Liver Lobes: Anatomists used landmarks to divide the liver into four anatomical lobes: right, left, caudate and quadrate (Image J). The large, right lobe (tan) is separated from the smaller left (yellow) by one of the membranes mentioned above, the falciform ligament. Only by viewing the undersurface are caudate (blue) and quadrate (green) lobes visible; caudate is nearer the spine and quadrate lies adjacent to gallbladder.

Image J

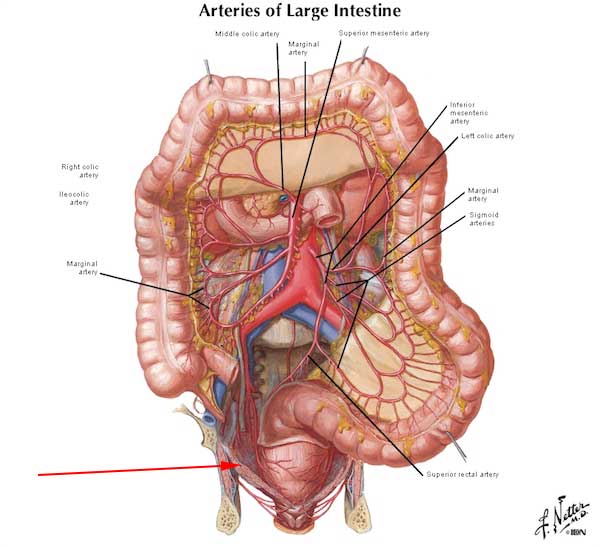

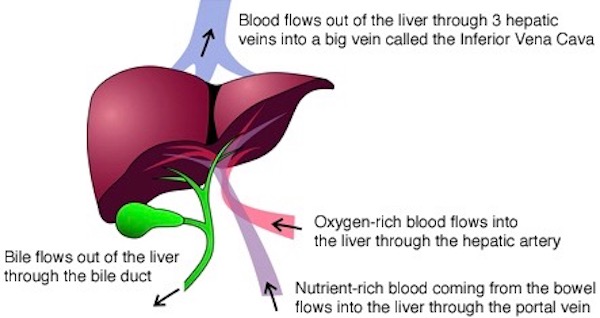

Blood Supply: Most organs receive blood via an artery and are drained by a vein. Not the liver! It is unique because it is the only organ receiving blood from both an artery and a vein; the hepatic vein delivers nutrient-rich blood derived from food digested in the gut, and the hepatic artery supplies oxygen-rich blood via the aorta. Three hepatic veins drain the liver (Image K).

Most organs are variations of a scarlet color because they receive oxygenated blood. Liver is a red-purple color because 75% of its blood supply is deoxygenated, nutrient-rich blood from the hepatic vein.

A dear long-time friend had a bit of trouble last year. Tests revealed that she had lost the blood supply to a segment of her liver with subsequent death of said segment! Cause unknown. She has given me permission to share this experience because it is unusual given she lacks any history of typical liver disorders or diseases. This is a wonderful example, though, of how dependent the liver is upon an intact blood supply!

Image K

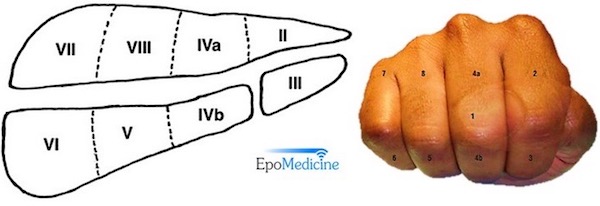

Clinical Liver Segments: The next image looks scary, but bear with me here! Clinicians divide the liver into eight separate segments, numbered 1-8 or I-VIII (Image L); segment I (1) lies deep to IVa (4a) and IVb (4b), so it is not visible. Segments II and III lie to the left of the falciform ligament; all other segments lie to the right. Segmental divisions are determined by vascular supply and bile duct branching (see below) and are of great clinical import!

Image L

Clinical Liver Segments (cont.): Let’s say a cancer is found in liver segment IVb (4b). A competent surgeon determines the probable boundaries of IVb and resects only that segment, sparing remaining liver segments and minimizing blood loss. The surgeon performing these highly specialized surgeries must be thoroughly familiar with the segmental design as defined in Couinaud’s system (Image M).

Medical students have difficulty memorizing liver segments, but this fist mnemonic offers a useful visual. Note that the thumbnail (seen in ghost) represents the deep-lying, segment I.

Image M

Outlandish Lobes: Speaking of liver lobes… like you, I was deeply impressed by Master Raymond’s ministrations to Claire (and her liver) after her loss of Faith-faith (Starz episode 207, Faith). Her liver and other organs were infected; she probably had puerperal fever, a post-partum infection of the uterus that, if untreated, usually becomes systemic. Serious-Sobbing here (Dragonfly in Amber book)!

An odd feeling of warmth now emanated from those broad, square, workman’s hands. They moved with painstaking slowness over my body, and I could feel the tiny deaths of the bacteria that inhabited my blood, small explosions as each scintilla of infection disappeared. I could feel each interior organ, complete and three-dimensional, and see it as well, as though it sat on a table before me. There the hollow-walled stomach, here the lobed solidness of my liver, and each convolution and twist of intestine, turned in and on and around itself, neatly packed in the shining web of its mesentery membrane.

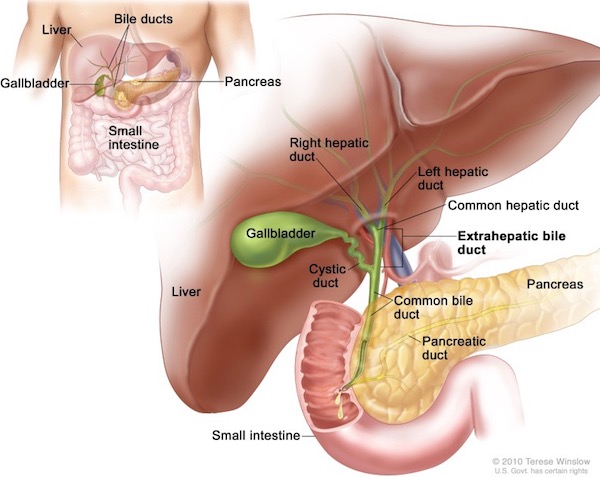

Bile Ducts and Gallbladder: Liver enjoys a robust working relationship with gallbladder and bile ducts. Why? Because, liver cells continuously produce bile, a dark green to yellowish-brown fluid. Bile is transported by a converging system of bile ducts from liver to gallbladder, a bag-like structure which stores and concentrates bile (Image N). Bile is then released in a controlled fashion after chyme (Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach, Wobbly Wame) enters the duodenum. In folks lacking a gallbladder, bile ducts continuously release bile into the duodenum.

Bile: Two important purposes are served by bile:

- Digestive aid: After eating a meal (especially high in fat), bile is released from gallbladder into duodenum (Anatomy Lesson #47, Brave Bowels – Gurgly Gut!) where it aids in lipid digestion by fats emulsification.

- Excretory product: Specialized liver (Kupffer) cells devour effete red blood cells, breaking down hemoglobin into bilirubin, a waste component of bile that is eliminated with the stool.

Bile enjoys a long history in western medicine. From 500 B.C. to the early 19th century, standard practice adhered to a four humor system: black bile, yellow bile (liver bile), phlegm, and blood. Excesses of black and yellow biles were thought to produce depression and aggression and were treated accordingly (sometimes with phlebotomy). If only physiology/psychology were that simple!

Image N

Hepatocytes: The hepatocyte is the main functioning cell of the liver (there are other cell types, too). It’s prefix derives from the Greek word, hepar, meaning liver. Microscopically, the hepatocyte (image O – arrows point to hepatocyte cell membranes) is a large, round, bland-looking cell, but what a power-house it is!

Hepatocytes are arranged into 1-2.5mm cylinders, each known as a liver lobule. I will not teach liver lobule structure here as it is complex and difficult to understand for students lacking histology training – beyond the scope of this anatomy lesson. Suffice it to say that the liver is packed with millions of these tiny liver lobules. Their designs allows hepatocytes to have immediate access to blood vessels and bile channels. This allows ready access to substances in the blood stream and to release bile into bile channels for transport to the gallbladder.

Image O

Image P is a nice graphic summarizing a few liver functions – most are self-explanatory. Hepatocytes are responsible for almost all the ∼500 liver functions. Just a note about the Kupffer cell (Image O – arrowhead). a phagocyte, meaning “eating cell.” Kupffer cells ingest effete red blood cells (and other things), turning hemoglobin into bilirubin, a component of bile. Just consider: maintaining such a huge organ would be wasteful if it weren’t highly important – it wears many hats!

Image P

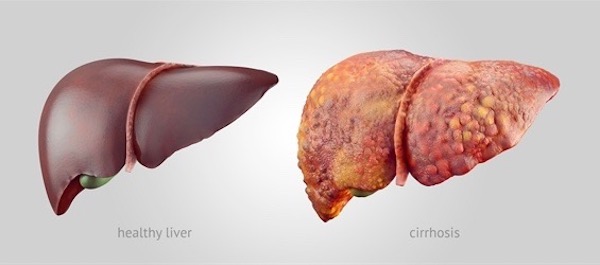

Liver Diseases: Liver is subject to a staggering array of diseases – from genetic disorders, autoimmunities, viral hepatitis, and parasitic liver flukes to cancer, chronic alcohol disease, poisoning, drug abuse, excessive use of over-the-counter pain relievers, etc. Although liver has a tremendous capacity to regenerate, long-term damage may result in the formation of scar tissue. A scarred liver is characteristically bumpy, a condition known as cirrhosis (Image Q). In the 18th century, Claire would have said the patient with a cirrhotic liver was liver-sick and cirrhotic livers were termed hobnailed livers. Just so you ken, hobnails are a short, heavy-headed nails used to reinforce the soles of boots. Bless Diana’s heart, she even wrote about cirrhotic livers (Dragonfly in Amber book)!

I knelt by the small traveling chest, unfolding the green velvet. Kneeling next to me, Jamie flipped back the lid of my medicine box, studying the layers of bottles and boxes and bits of gauze-wrapped herbs. “Have ye got anything in here for a verra vicious headache, Sassenach?” I peered over his shoulder, then reached in and touched one bottle. “Horehound might help, though it’s not the best. And willow-bark tea with sow fennel works fairly well, but it takes some time to brew. Tell you what—why don’t I make you up a recipe for hobnailed liver? Wonderful hangover cure.”

Liver dialysis can be used as a stop-gap treatment, but liver transplant is the only current option for complete liver failure. If all goes well, the transplant regenerates much of the original liver mass.

Image Q

Leaving that unhappy liver-note, let’s end on a happier liver quote!

Recall Starz, episode 105, Rent? One of my favs.

Intruder alert! With a massive candle stick, Claire goes after someone fussing outside her door!

Dashing outside, she encounters Jamie, sprawled on the filthy floor. “What are you doing here?” she demands (Outlander book), after stepping on his RUQ. Watch out lovely, lively liver! Crunch!

“What are you doing here?” I asked accusingly. At the same time Jamie asked, in a similarly accusatory tone, “How much do ye weigh, Sassenach?” Still a bit addled, I actually replied “Nine stone,” before thinking to ask “Why?” “Ye nearly crushed my liver,” he answered, gingerly prodding the affected area. “Not to mention scaring living hell out of me.”

Nurse Claire, in the hallway with a candlestick? <G> She almost brains Master Fraser! And her weight? What gently-bred Scottish lad asks a lass how much she weighs? Geez, at 126 lbs, Claire is a just wee thing!

And, Jamie, you drink Scotch whiskey so we all ken your liver can take a trashing! Uh oh, we’ve seen that look before. Run, Claire, run! Hah!

So, the liver may look boring, but is a bundle of life: 500 duties it performs to keep our bodies healthy and happy. We literally live in our liver!

Let’s end this lively liver lesson with a great quote from American physician and psychologist, William James:

Is Life worth living? It all depends on the liver.

And, from my own pen:

Liver the giver

makes us shiver and quiver

bound to deliver

It’s a major caregiver!

So, Love your Liver!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Photo Creds: Starz, www.techmeanatomy.info (Image J), www.arthistorynewsreport.blogspot.com (Image C), www.cojs.org (Image B), www.commons.wikimedia.org (Image H), www.diets-usa.com (Image A), www.epomedicine.com (Image M), www.kenhub.com (Image F), www.medhealthdaily.com (Image G), www.medvizor.com (Image P), www.nature.com (Image L), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (Image N), www.pathpedia.com (Image O), www.pinterest.com (Image I), www.skylerzarndt.com (Image E), www.vaxy.com (Image Q), www.wikipedia.org (Image D), www.24nurse.com (Image K)