Welcome, all anatomy students to Anatomy Lesson #34, The Amazing Saga of Human Anatomy! This topic is a divergence from our usual Outlander themes but before you decide to skip it, please consider that herein lays oodles of interesting illustrations and startling titbits about the checkered past of human anatomy. This blog doesn’t have the luxury of covering all of anatomical history as entire books have been written on the topic so it covers only major milestones relating to western medicine.

But first, is tying the history of anatomy into Outlander a reach? Nay, anatomy, especially abnormal anatomy (pathology) is all over the place in Diana’s books and the Starz series. Anatomy follows Nurse Claire, like… well, like girls cling to Jamie! From the moment she steps into Davie Beaton’s surgery (Starz episode 101, Sassenach), her senses are on high alert: déjà vu, sixth sense, the training of a scientist? Hmm…there’s something mighty eerie about this place.

Claire’s anatomical knowledge is required during her first encounter with Jamie as Herself wrote in Outlander book:

You have to get the bone of the upper arm at the proper angle before it will slip back into its joint,” I said, grunting as I pulled the wrist up and the elbow in. The young man was sizable; his arm was heavy as lead.

Claire successfully realigns Jamie’s humerus and glenohumeral joint thereby reducing the dislocation (Starz episode 101, Sassenach). Read about the technique Claire used in Anatomy Lesson #2, “When Claire Meets Jamie” or “How to Fall in Love While Reducing a Dislocated Shoulder Joint!”

Now for our lesson: anatomy is the oldest of the medical sciences with a rich and very blemished history. The word “anatomy” derives from the Greek ana “up” and temnō “I cut”, implying dissection (pronounced dis-section not di-section) of an organism to discern its design. Anatomy is the study of the structure of organs, tissues and cells through all stages of maturation. The anatomist is concerned with names, shape, size, position, relationships, blood supply and innervation of structures while physiologists study function and biochemists follow processes, although these distinctions typically blur in the research lab.

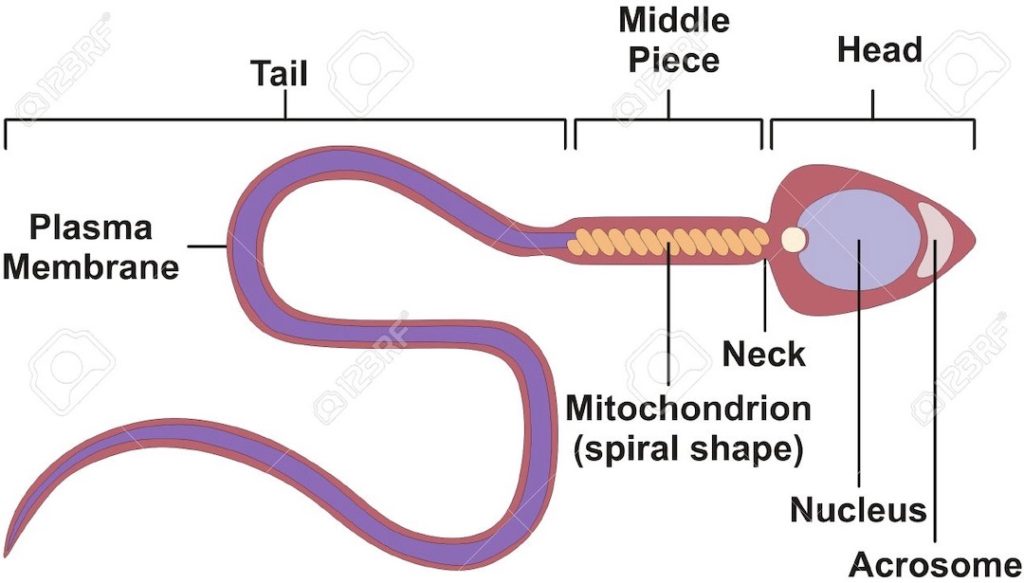

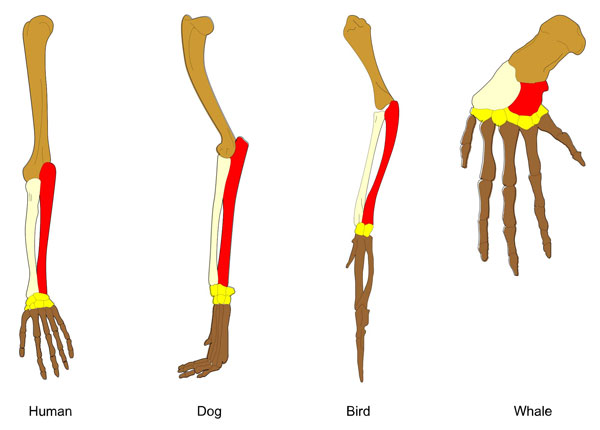

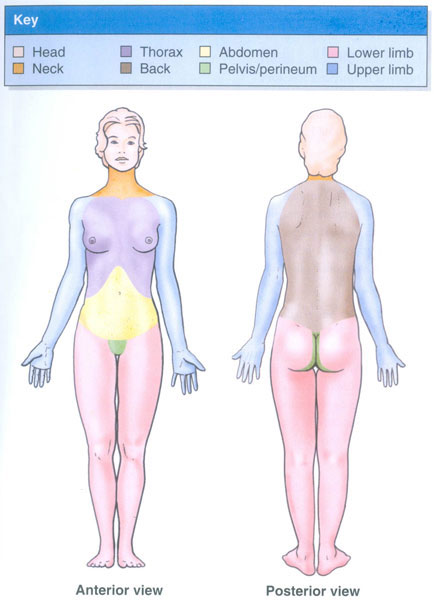

Nowadays, anatomy is a tree with many branches: Zootomy is the anatomy of all animals; phytotomy is the anatomy of all plants. Comparative anatomy contrasts anatomy between species. Anthropotomy (an-thro-pot-o-my) is the proper (but rarely used) term for anatomy of the human body. Gross anatomy describes structures that are visible with the naked (unaided) eye. Microscopic anatomy (histology) uses magnification to study cell, tissue and organ structure. Surface anatomy focusses on an organism’s external features. Developmental anatomy (embryology) studies structures of the developing organism. Radiologic anatomy employs imaging modalities such as x-ray, ultrasound, MRI or CT to reveal internal structures. The following images are examples of two such fields of anatomy.

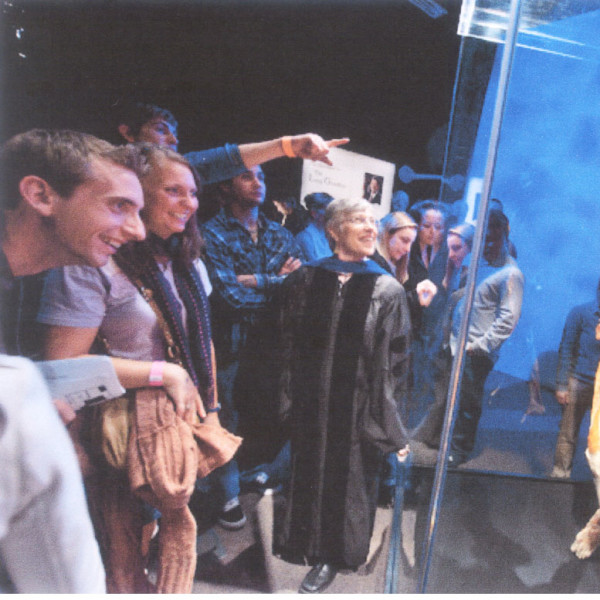

This image shows comparative anatomy of the upper limb from four different animals: shape, size and disposition of corresponding upper limb bones are contrasted and compared. Homologous (comparable) bones are color coded for ease of identification (Image A).

Image A

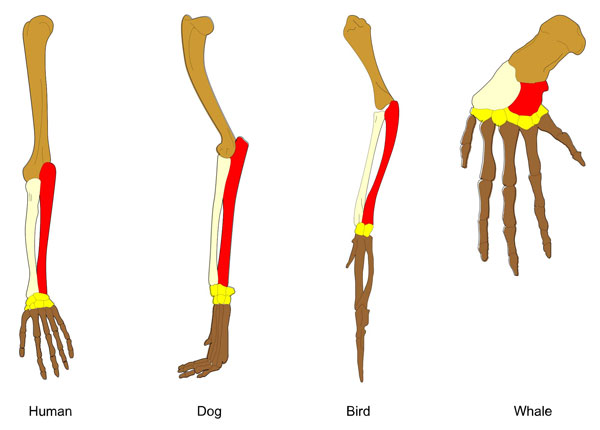

The next image shows a poignant example of radiologic anatomy: an MRI scan reveals brain anatomy of a mother tenderly cradling her sleeping child as they nest within the tube of an MRI scanner (Image B). The neuroscientist overseeing this work pursues the field of brain development. Surprisingly, she informs us, “… I am a neuroscientist, and I worked to create this image; and I am also the mother in it curled up inside the tube with my infant son.”

Image B: MRI from Smithsonian, December 2015

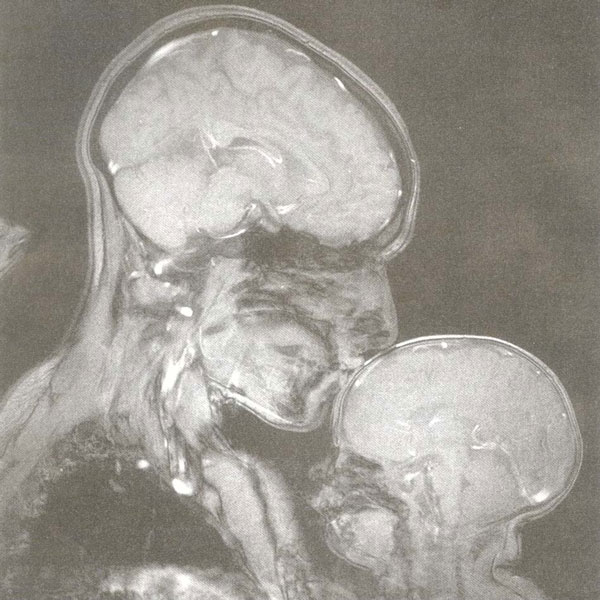

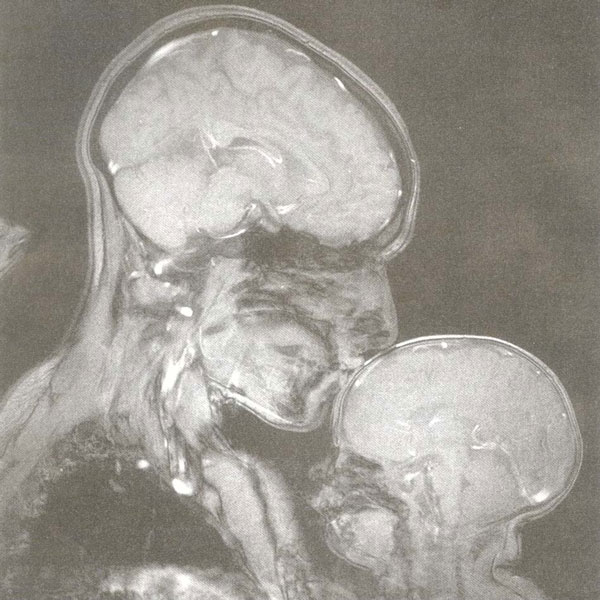

Human anatomy is the foundation of medicine and is typically the first course taught in medical curricula; when appropriate, cadaveric dissection lies at its core (Image C). Why is this so? Well, if your beloved dishwasher, car, or god forbid, computer goes on the blink, you wouldn’t want joe blow tinkering with it would you? Likewise, who hands their body over to a practitioner who knows next to nothing about its design? Not me!

As course director of gross anatomy (now retired), I routinely told my first year medical students: “The human body is a living, breathing, basic science laboratory and you get to take care of it; it is best that you know your anatomy well!”

Image C: Dissection by Body Region

An important consideration: Religion and science are periodically at odds in the anatomical time line as they are often viewed as opposing forces – in my thinking, they are not because they ask and answer different questions.

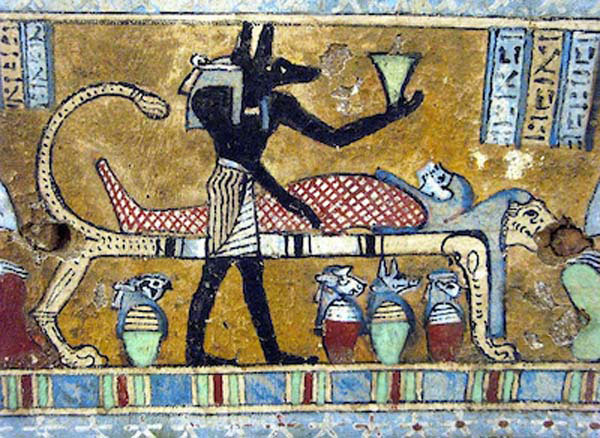

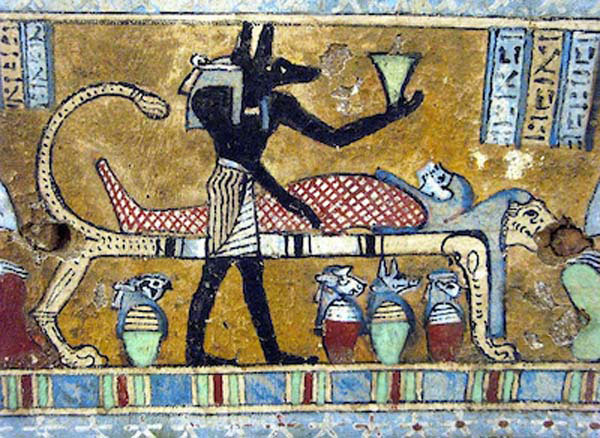

The roots of human anatomy arguably began about 2,600 BCE with the religious practices of ancient Egypt; a culture that believed mummification allowed a soul to retrieve its preserved body before journeying into the underworld. Heart, lungs, liver and bowels were removed and stored in canopic jars (Image D) or treated and replaced into body cavities. The brain was removed (encephalectomy) via the nostril (preferably the left) but was destroyed in the process. These incursions into the body revealed anatomy to embalmers albeit for religious purposes. Egyptian physicians likely benefitted from such anatomical expertise because ancient papyri (e.g. Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri, ca. 1600-1500 BCE) contain highly sophisticated medical instructions for surgeons and physicians including such details as the first known appearance of the word for “brain”.

Image D: Anubis Oversees Embalming – from Sarcophagus of Pedusiri

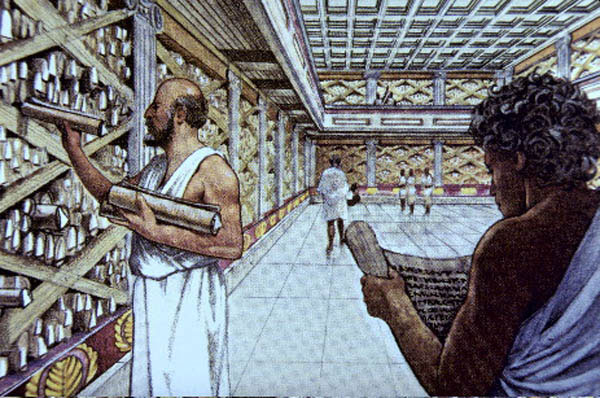

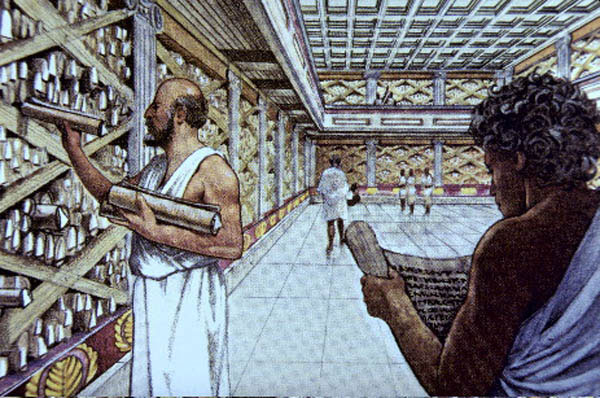

After Alexander the Great founded the ancient city of Alexandria, the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty began – a culture that deeply valued the natural realm much like the ancient Egyptians pursued the religious realm. Ptolemy I (367-283 BCE), successor to Alexander the Great, conceived the Library of Alexandria (Image E) aiming to make it the center of western knowledge.

Although forbidden in the ancient world, Ptolemy I legalized dissection and released the bodies of condemned criminals for this purpose (unethical by today’s standards). Thus, in the 3rd century BCE, Greek physicians Herophilus and Erasistratus began the first known human dissections for scientific purposes. Their meticulous work laid the foundation of human anatomy and corrected many misconceptions embraced by practitioners of medicine but their texts were destroyed with the Alexandrian library.

Three hundred years later, following the rise of Christianity, both anatomists were denounced as “butchers of Alexandria” and accused of dissecting living humans. This denouncement came centuries later and although widely circulated as truth, the accusations are based on inference. Subsequently, human dissection was deemed blasphemous and outlawed leaving practitioners of western medicine woefully ignorant of human anatomy.

Image E: Library at Alexandria

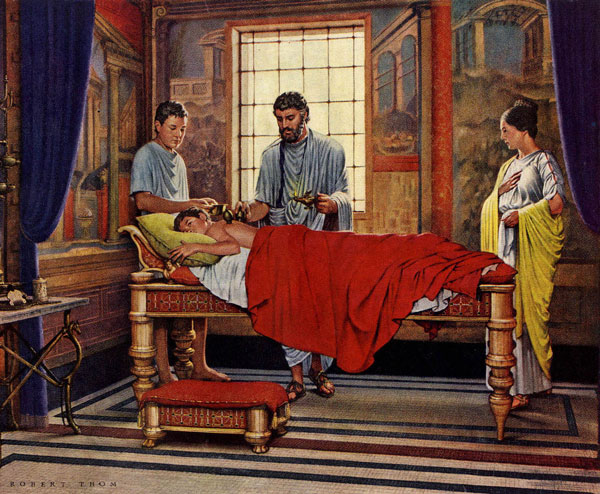

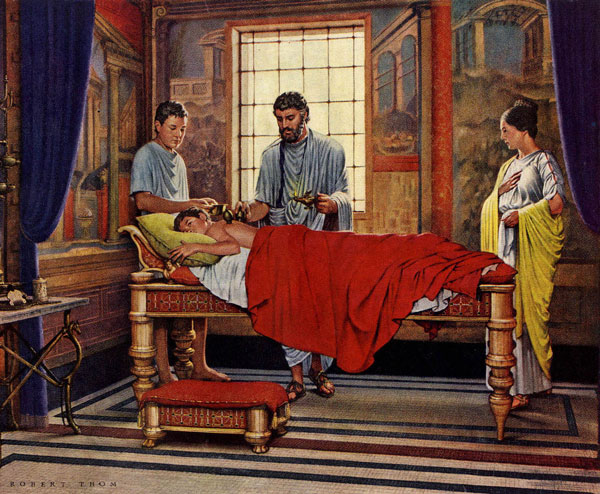

Enter one Claudius Galenus (Galen) of Pergamon (130 – c. 200 CE), a Greek who was born and raised in present day Turkey (Image F). Widely educated, he chose a career in medicine, eventually settling in Rome as physician to the gladiators. There, he achieved fame through accurate diagnoses, treatments, public lectures, discussions, demonstrations and writings. He correctly diagnosed Emperor Marcus Aurelius’ ailment as indigestion, for which he was appointed court physician.

Galen performed animal dissections and the anatomy was inferred to humans. His writings and teachings were marked by brilliant observations and wise therapeutic application but also by colossal error and pompous hubris. His ego was monumental as evidenced by this quote:

Never as yet have I gone astray, whether in treatment or in prognosis, as have so many other physicians of great reputation. If anyone wishes to gain fame all that he needs is to accept what I have been able to establish.

Galen was the last great Greek physician-scientist of the ancient world. His writings in Greek were lost but survived in Latin, Arabic and occasionally, Hebrew translations. After Galen, anatomical research ceased and his flawed texts became the ultimate medical authority for over 1200 years!

Image F: Galen by Robert Thom

Over the next millennium, anatomical images became firmly linked with astrology and magic. Mistress Claire was confronted with this reality when Colum assigned her to Davie Beaton’s “closet of horrors” at Castle Leoch. Lifting the lid of a medicament chest, the top displayed the woeful state of anatomical knowledge at Beaton’s “Skulkery”: a rudimentary image of human organs linked to signs of the zodiac (Starz episode 103, The Way Out). The sight draws a faint smile from our resident anatomist. And, Herself recorded:

There were a number of more or less harmless substances in Beaton’s jars, as well as several containing dried herbs or extractions that might actually be helpful… I discarded jars of dried snails; OIL OF EARTHWORMS which appeared to be exactly that; VINUM MILLEPEDATUM millipedes, these crushed to pieces and soaked in wine; POWDER OF EYGYPTIANE MUMMIE an indeterminate-looking dust, whose origin I thought more likely a silty streambank than a pharaoh’s tomb; PIGEONS BLOOD, ant eggs, a number of dried toads painstakingly packed in moss, and HUMAN SKULL, POWDERED. Whose? I wondered…

Returning to our anatomical time line, let’s fast forward a brief millennium (ha!) during which political and religious powers outlawed human dissection. However, gradually, religious authorities changed their attitudes and legislations were enacted to allow human dissection for teaching purposes.

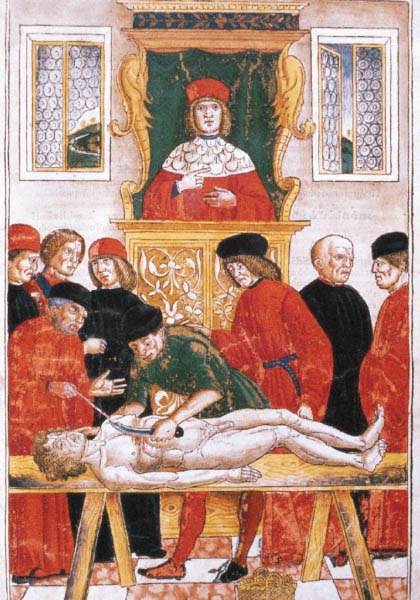

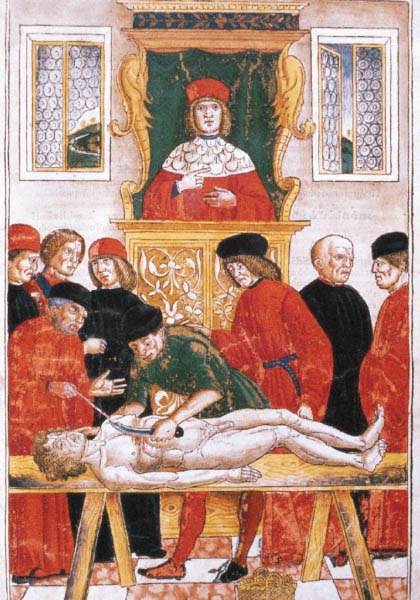

These events culminated in the first officially sanctioned human dissection since Herophilus and Erasistratus, performed by physician-anatomist Mondino de Cuzzi (1275-1326) of Bologna. Human dissection quickly spread to other European universities, the process immortalized in a woodcut from the first anatomical text ever printed (Image G). This puzzling image requires a note of explanation: three individuals were involved in the aforementioned dissection. A lecturer orchestrated the affair from a raised dais while reading from anatomical texts, usually Galen. A barber surgeon performed the dissection and the individual to his right (your left) identified the structures. The elevated position of the lecturer is thought to be the origin of the term chairman of the department. The individual using the baton to identify structures became known as the demonstrator of anatomy.

Image G: First print of Human Dissection

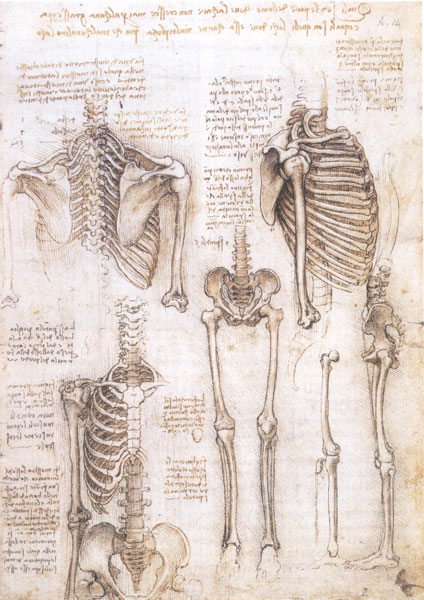

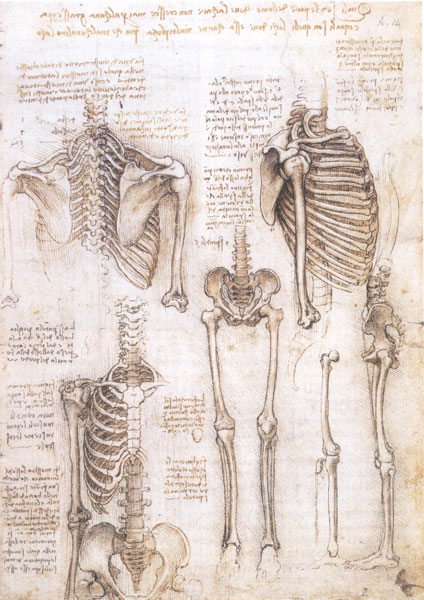

The history of anatomy would be incomplete without mentioning archetypal Renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). During his lifetime, only physicians or barber surgeons could legally dissect human cadavers but da Vinci received a special church dispensation to perform his own dissections; from these, he created the earliest and most accurate anatomical sketches (Image H). Although his paintings were famous, only a few close associates knew of his anatomical research. Unfortunately, da Vinci never worked as a professional anatomist; he never taught the subject and never published his observations which would have greatly advanced the science of anatomy (Anatomy Lesson #20, Arms! Arms! Arms! – Redux). In the meantime, dissection at universities continued to involve lecturer, barber surgeon, demonstrator of anatomy and Galen.

Image H: Human Skeleton by Leonardo Da Vinci

Our next major milestone is embodied by one Andreas Vesalius (1514 – 1564); born in Brussels, he descended from a long line of medical men. During his studies at University of Paris, he became convinced that human dissection was vital to understanding structure and function (Image I). To that end, he visited gallows and cemeteries to obtain specimens which he studied until he could identify any human bone blindfolded. Later, at the University of Padua, he graduated as Doctor of Medicine with highest distinction and the following day, at 23 years old, he was appointed Professor of Surgery! With good reason Vesalius is generally considered the “father” of modern human anatomy.

Image I: Andreas Vesalius by Edouard Hamman

Understand that at this time, professors believed Galen’s teaching so infallible that should dissections yield information contrary to his writings then either the cadaver was abnormal or mankind’s decadence and degeneration had caused anatomy to change since Galen!

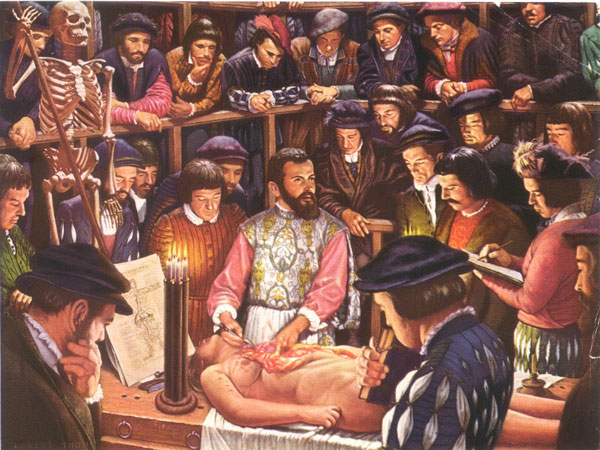

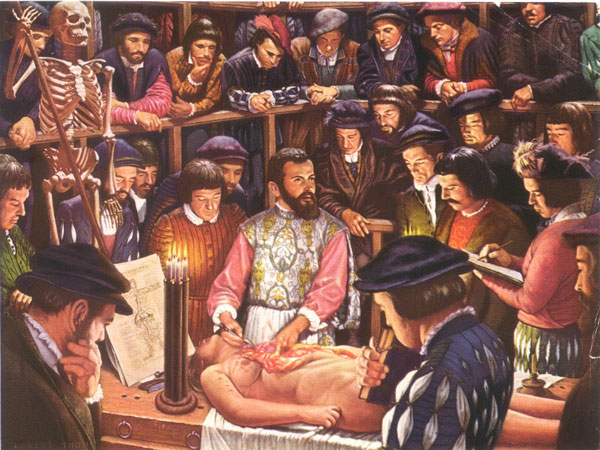

Discovering by direct observation that 1400 years of Galen’s anatomy were wrong, Vesalius performed a public dissection to demonstrate correct anatomy and dissuade those attached to Galen’s theories (Image J – yes, it was a woman). His public demonstrations continued and proved so successful they attracted medical students, physicians, civic officials, sculptors, and artists. While admired, Vesalius’ work also incurred wrath and vilification by those who considered Galen to be infallible.

The following is a brief list of Vesalius’ work that corrected Galen’s mistakes; his accomplishments are staggering:

- Accurately described sphenoid and temporal bones (bones of skull)

- Human sternum made of three fused bones (Anatomy Lesson #15)

- Sacrum made of five fused bones (Anatomy Lesson #10)

- Hepatic veins (of the liver)

- Azygos vein (of thorax – Anatomy Lesson #15)

- Ductus venosus (fetal blood vessel)

- Omentum (large abdominal membrane)

- Stomach and its pyloric region plus spleen, colon and appendix

- Pleurae (membrane surrounding each lung)

- Lungs

- Brain and most of the cranial nerves (nerves arising from the brain)

- Four chambers of the heart (Galen declared there were two)

- Great vessels carrying blood to and from heart

- Mandible as a single bone (Anatomy Lesson #26)

- Ventilation (respiration)

Vesalius also proved that the human spine does not contain the revered bone of Luz, a bone that by religious and cultural tradition was deemed indestructible and required for resurrection of the body.

Image J: Vesalius’ Public Dissection by Robert Tomm

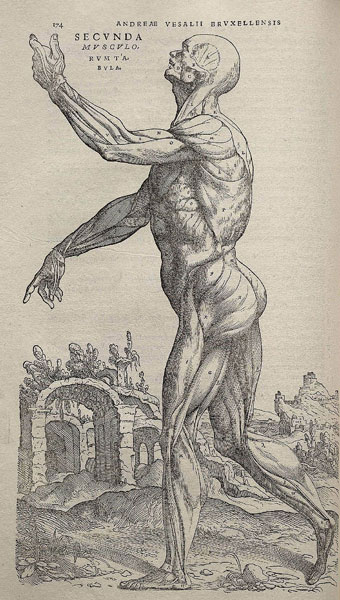

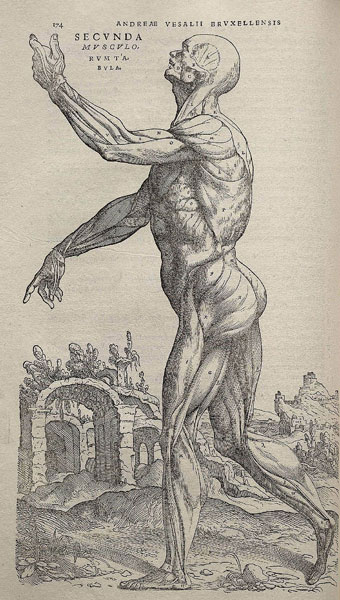

In 1543 Vesalius wrote the monumental De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), the most comprehensive anatomical text yet written and arguably the greatest single contribution ever made to human anatomy. Fabrica displayed brilliant illustrations created as intricate woodcut plates by various artists from the “studio of Titian”. Bodies in varying degrees of dissection are arranged in allegorical poses complete with pastoral environs (Image K). During the 20th century, Vesalius’ original plates were housed in Munich but, sadly, a World War II bombing raid destroyed them.

Image K

Again in 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection on the body of a notorious felon. Later, he assembled the bones and donated the skeleton to the University of Basel. This preparation (“The Basel Skeleton”) is the world’s oldest surviving anatomical preparation and is still displayed at the Anatomical Museum of the University of Basel (Image L).

Later, Vesalius served as court physician to Emperor Charles V and his son. He died at the age of 50 on a Greek island during a return trip from the Holy Land. To the present day it is claimed that Vesalius was forced on the pilgrimage for performing an autopsy on an aristocrat while the heart was still beating. Modern historians consider this story without merit because it was circulated by a competitor. There is an odd bit of wisdom that states, academic fights are so bitter because there is often so little at stake (grin)!

Image L

Time for a brief break and another anatomy lesson from Mistress Beauchamp! This time she ascertains that Geordie’s femoral artery (Anatomy Lesson #9, The Gathering or Gore By a Boar) was not severed by the wild boar’s tusk so she should be able to stem the bleeding (Starz episode 104, The Gathering) . Sadly, this hopeful thought was quickly amended as she spied puir Geordie’s fatal abdominal wound. We read in Outlander book:

There was a deep wound, running at least eight inches from the groin down the length of the thigh, from which the blood was gushing in a steady flow. It wasn’t spurting, though; the femoral artery wasn’t cut, which meant there was a good chance of stopping it.

Following the work of Vesalius, human anatomy enjoyed a brilliant burst of anatomical illustration; artists and anatomists sometimes competing for elegant form versus anatomical accuracy. The result is some of the most famous and astonishingly beautiful anatomic illustrations ever created. Consider the priceless 1632 painting by Rembrandt “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicholaes Tulp” (Image M). This painting recreates another public dissection and while undeniably elegant and riveting, it is also anatomically incorrect. Why? Well, because Rembrandt wasn’t an anatomist so details such as the correct origin of the long flexor muscles of the digits (see Anatomy Lesson #22, Jamie’s Hand – Symbol of Sacrifice) were misrepresented.

Image M

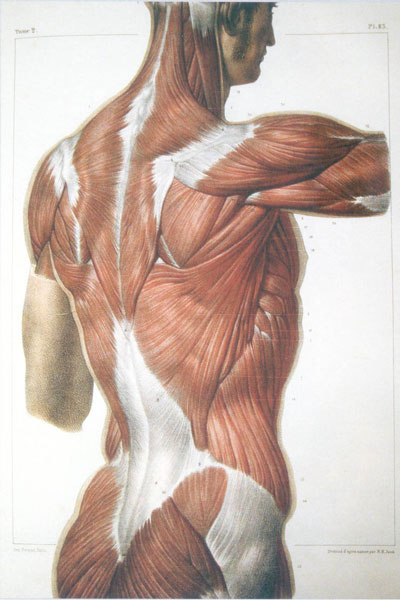

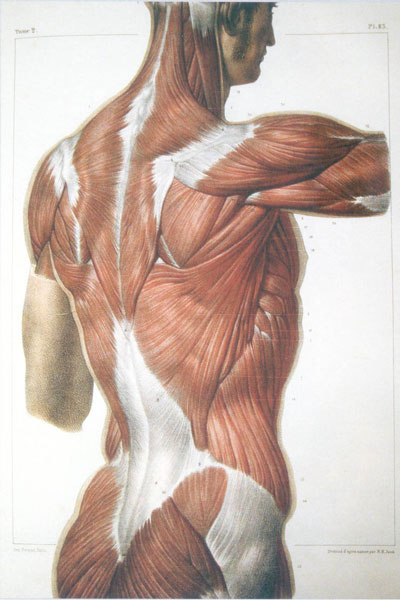

Then, in 1871 an eight volume compendium Traite’ complet d’anatomie de l’homme (Complete Treatise of the Anatomy of the Man) was published by French anatomist Bourgery, and illustrator Jacob (Image N)! Their anatomical images combined accuracy with elegance and are amongst the most beautiful ever rendered.

Anatomical illustrations were created by other famous Renaissance artists such as Bidloo, Donatello, Michelangelo, Titan, Rembrandt, Albinus, D’Agoty, Genga, and Ruben. And, models depicting human anatomy exploded on the scene: carved from ivory, made of papier-mȃché, copper engravings, woodcuts, chalk, wax, bronze, and finally by the end of the 19th century, photography.

Image N

Today’s anatomical “bible” is, of course, Gray’s Anatomy. My own 39th edition is a real door stopper! Weighing in at 10 pounds, the single-spaced text appears in size 8 font and more 1500+ pages in length! And, it still doesn’t contain all that currently is known about human anatomy.

The size of this giant tome is somewhat amusing as the book was conceived in the 1850s by 28 year old Henry Gray (Image O), a teacher at St. George’s Hospital Medical School, London. Sharing his idea with artist and colleague, Dr. Henry Vandyke Carter, who was also Demonstrator of Anatomy at St. George’s, the pair conceived a light weight (hee hee), well-illustrated, and accurate pocket text designed for students. The first edition (1858) was an instant success; periodically updated and enhanced, it has been published continuously for over 150 years!

Poor Henry enjoyed a successful but short life. While attending to a nephew ill with smallpox (Anatomy Lesson #21, Small Pox and the Devil’s Mark), Henry fell victim to the disease and swiftly died at the youthful age of 35.

Image O

Please understand that a discussion of anatomical history is incomplete if limited to structures discoverable in a dissection lab as our bodies are made of cells and tissues elements that are invisible to the naked eye. Identifying these structures required the invention of magnifying lenses.

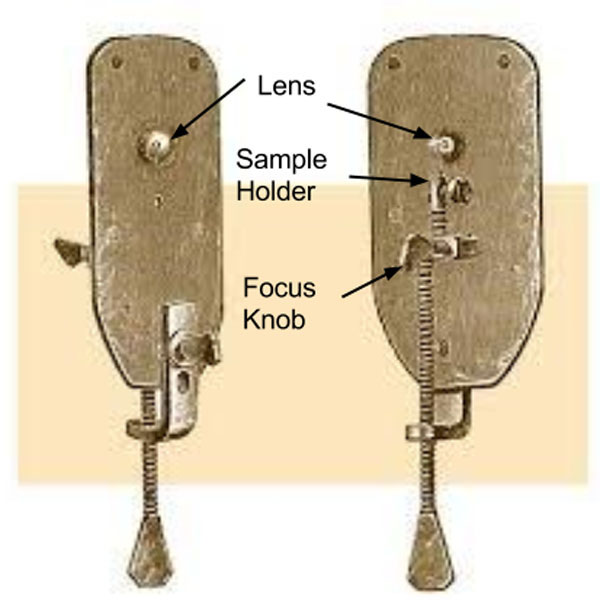

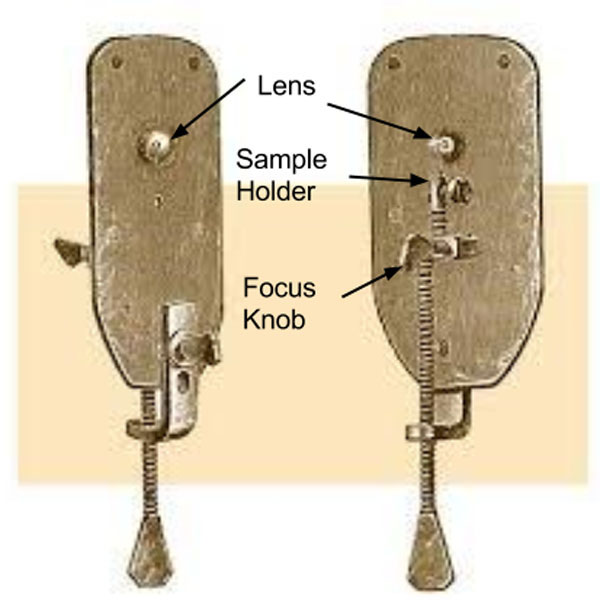

Enter Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), a Dutch draper (merchant of fabrics). Wishing to assess the quality of woven threads, Van Leeuwenhoek determined to improve their visibility. Microscopes existed in his time but the best could only magnify 9x – meaning 9 times the size of the object observed. Self-taught, Antonie began experimenting with glass processing and lens making. Working in a hot flame with small rods of soda lime glass, he created tiny, high-quality glass spheres to use as single lenses which he housed in small silver or copper frames – these became his simple microscopes (with one viewing lens). These tiny handheld instruments were only about 5 cm (2”) long but capable of 275x magnification! He created 25 simple microscopes, several of which still survive (Image P).

Image P

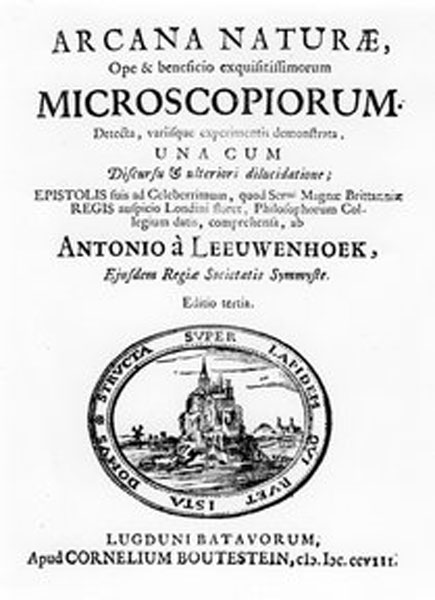

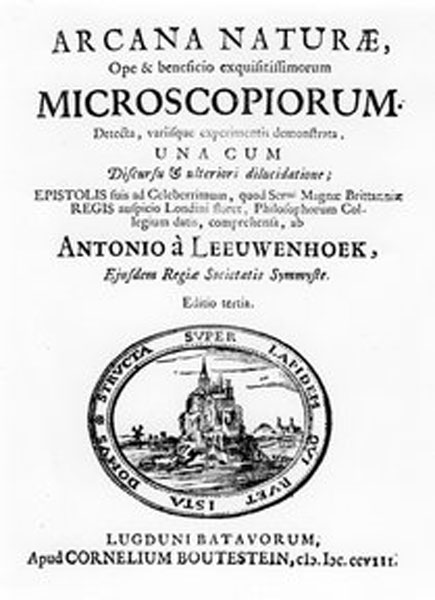

Turns out, van Leeuwenhoek examined much more than threads! Eventually he sent The Royal Society a manuscript, Microscopiorum, complete with written descriptions and meticulous drawings of single-cell life (called animalcules) including spermatozoa, red blood cells (erythrocytes), bacteria, yeasts and life forms in a drop of water, all observed with his microscopes. Although his lens research was heartily embraced by the Society, his biologic findings were initially met with skepticism and derision, an old but common experience in the field of science (Image Q).

Image Q: 3rd edition of Microscopiorum

Fast forward three hundred years to a modern compound light microscope (Image R). Like the earliest microscopes, compound microscopes use light from the visible spectrum to illuminate an object but they also employ two lenses to achieve greater magnification: one near the eye and one near the object viewed, hence the term, compound.

Image R

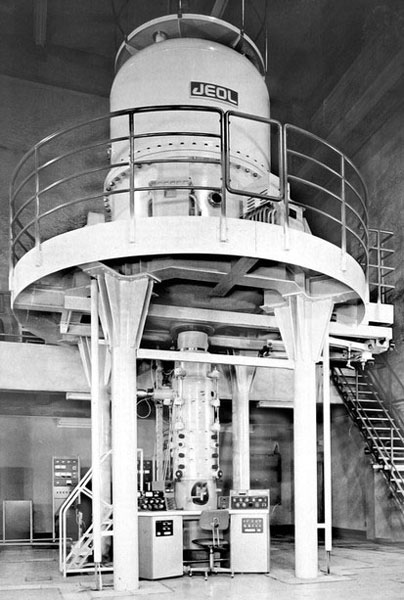

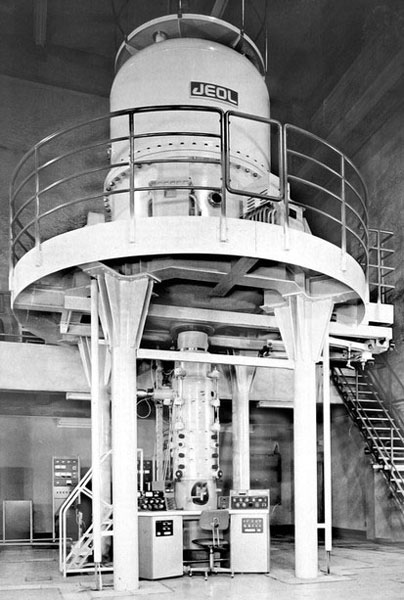

In the 1930s, the electron microscope was invented substituting a electromagnetic lens for glass. It also used a high voltage electron beam not light waves to illuminate an object. Today, there are different types of electron microscopes including the transmission (TEM) and scanning or (SEM) electron microscopes (Anatomy Lesson #6).

Typical TEMs magnify objects about 500,000x although some can magnify much more and are able to reveal subcellular structures. Image S shows a 1,000,000 volt electron microscope at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, one of only a handful in the world. In the ‘80s I took micrographs (photographs taken with a microscope) on one of these big boys in Colorado. The instrument was three stories tall and hummed like Luke Skywalker’s light saber!

Microscopes have opened a new world to researchers and students allowing health practitioners to understand the cellular and subcellular basis of health and disease.

Image S

Time for another example of Claire’s anatomical expertise: who can forget the image of Jamie’s puir hand mangled by Black Jack the Ripper (Starz episode 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul)?

Claire reveals her anatomical chops once again by describing the extent of Jamie’s wounds. Here from Outlander book:

I took his good hand as well, and felt carefully down each finger of both the good hand and the injured, making comparisons. With neither X rays nor experience to guide me, I would have to depend on my own sensitivity to find and realign the smashed bones… I began to lose myself in the concentration of the job, directing all my awareness to my fingertips, assessing each point of damage and deciding how best to draw the smashed bones back into alignment. Luckily the thumb had suffered least; only a simple fracture of the first joint. That would heal clean. The second knuckle on the fourth finger was completely gone; I felt only a pulpy grating of bone chips when I rolled it gently between my own thumb and forefinger, making Jamie groan.

What a woman! What a man!

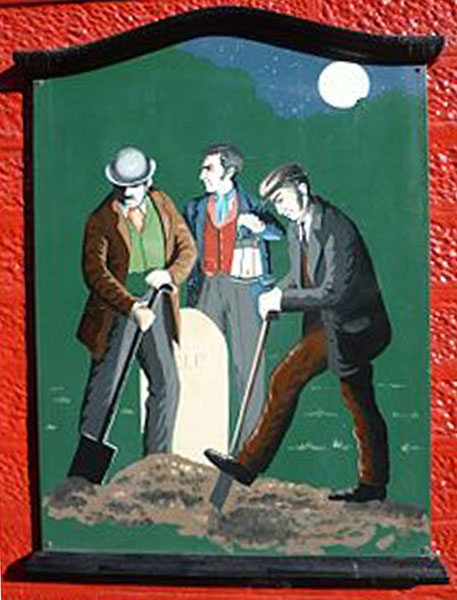

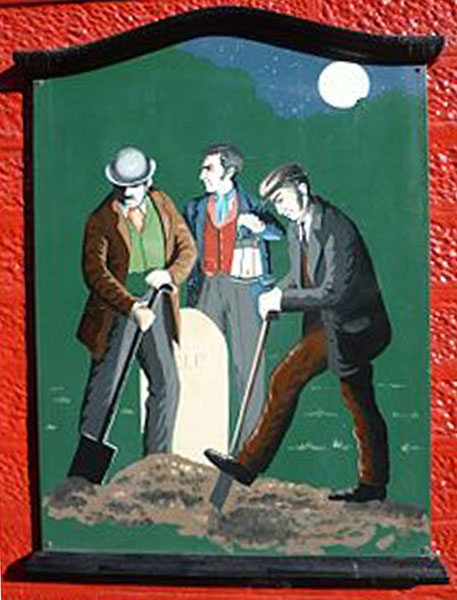

Back to our timeline: unfortunately, the explosion of anatomic knowledge and illustration from the time of Vesalius forward was marred by a dark underbelly: from 15th through the 19th centuries, bodies of executed criminals were relegated to the dissection lab as apt punishment for crimes. But, as capital punishment decreased, fewer bodies of criminals were available so some turned to grave robbing, body snatching and even murder to meet supply and demand (Image T). Bodies were then sold for dissection to students, teachers and schools of medicine.

Body snatching, by the way, is the surreptitious disinterment of bodies after burial. Those practicing body snatching were called resurrectionists or “bag ‘em up boys” (urban speak has a different meaning, och!). These practices became such a problem that some cemeteries built watchtowers and families hired guards to protect the graves of their loved ones.

There follows some heartily unsavory tales: 1827-1828, two Irish fellows, Burke and Hare, immigrated to Scotland where they murdered 16 citizens near Edenborough to supply corpses for medical dissection. Not to be outdone, across-the-pond cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York were also notorious for body snatching. But, England was the first to address such atrocities; the Anatomy Act of 1832 halted these activities by allowing unclaimed bodies and those donated by relatives to be used for the study of anatomy, and requiring the licensing of anatomy teachers. Unfortunately, many unclaimed bodies were those of poor people relegated to workhouses during a time when dissection was considered a just punishment for being poor!

Image T: Painting from a public house in Penicuik, Scotland

Finally, during the second half of the 20th century, universities, medical schools and hospitals employed trained anatomists for teaching and research. In addition, voluntary body donation programs arose as primary sources of bodies for anatomical dissection.

Nowadays, worldwide innovative programs are being introduced into body donation programs by medical schools to teach students respect, compassion and empathy towards the human body, dead or alive. Thus, human dissection is indispensable for many reasons:

- Teaches structure of the human body

- Provides the language of medicine

- Forms student’s first health care team

- Increases powers of observation

- Demonstrates anatomical variations as no two bodies are alike!

- Introduces student to pathology (abnormal anatomy)

- Becomes the student’s first patient

- Promotes humane qualities among future health care providers

- Allows surgeons and other specialists to safely develop new surgical techniques

- Provides new anatomical knowledge through research

At my university, I served three major roles: course director of gross anatomy, director of the body donation program, and demonstrator of anatomy (state legislated position). I also taught microscopic anatomy and embryology.

At the termination of the gross anatomy courses for which I was responsible, students (under supervision) organized and presented memorial services to honor body donors and their families. Poems, readings, music and numerous thank you messages were shared by the students with the families, after which donor families were invited to respond. No dry eyes in that auditorium!

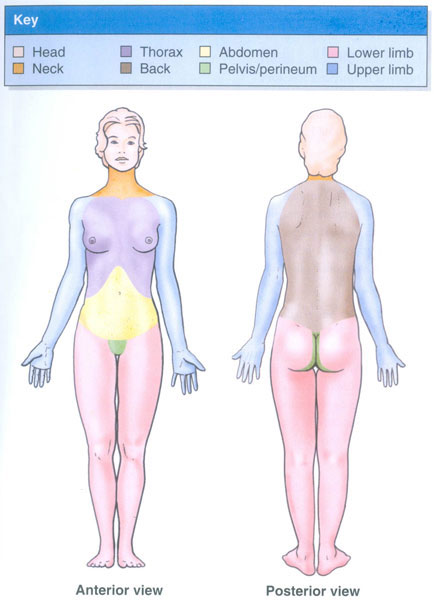

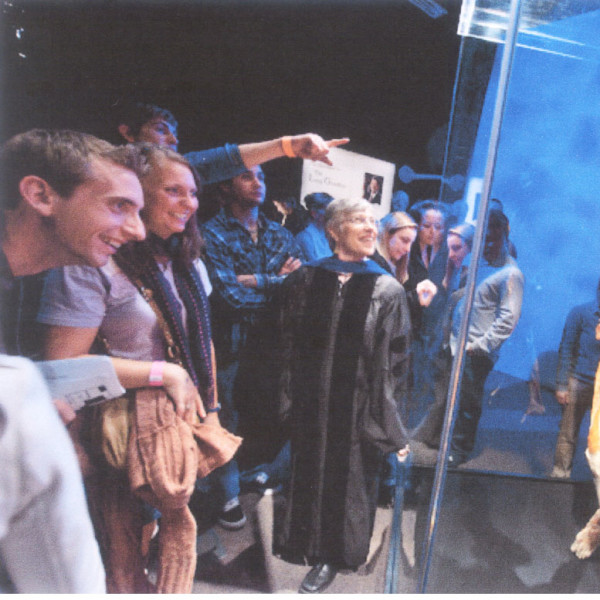

I’ve enjoyed teaching human anatomy to almost four decades of students: medical, physical therapy, physician assistants, respiratory technologists, and nursing students as well as surgeons and surgical residents, and the public (Image U – the excited grins are because a person recognized an anatomical structure they had always wondered about – no one was being disrespectful).

Image U: 2011 Body World Exhibit

I have had the privilege of dissecting and teaching dissection with more than 500 donor bodies and I deeply thank them for the privilege of learning from their temples of flesh. I can candidly state that dissecting the human body is an awe-inspiring honor that has forever changed me (Image V).

Image V: 2011 Body World Exhibit

This brings our saga of human anatomy to an end and will be my last anatomy lesson for 2015. I will continue to post anatomy Fun Facts until January of the New Year and then, a new anatomy lesson! Wishing you all the grandest and most glorious season ever!

Och, but dinna despair. The last words of this lesson are from Claire (and Jamie) who gave the world the finest appraisal and greatest appreciation of male human anatomy in the history of written literature (Starz episode 107, The Wedding). Snort!

Herself writes:

Because I want to look at you,” I said. He was beautifully made, with long graceful bones and flat muscles that flowed smoothly from the curves of chest and shoulder to the slight concavities of belly and thigh. He raised his eyebrows. “Well then, fair’s fair. Take off yours…”

Whew! Alrighty then – amen and amen!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Photo creds: Starz,, Bender, G. A. Great moments in Medicine. Northwood Institute Press, 1966 (Images F and J), Delaunay, ed., 1829 (Image N), Fasciculus Medincinae (compendium, authors unknown), 1491 (Image G), Greenspan, Robert E. Medicine Perspectives in History and Art, 2006 (Images H & M), Jean-Baptiste Marc Bourgery and Nicolas-Henri Jacob. Traite’ complet d’anatomie de l’homme, 1832- 1851. (Image N), Moore, Keith L. and Dalley, Arthur F. Clinically Oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006. (Image B), Outlander Anatomist, private collection (Images U & V), Smithsonian, December 2015. (Image C), www.anatomymyatlases.org (Image L), www.ancientpeoples.tumblr.com (Image E), www.colepaler.com (Image R), www.en.wikipedia.org Images A, K, O & T), www.fotolibra.com (Image Q), www.steninageo.com (Image S), www.study.com (Images D & P), www.thephysicianspalate.com (Image I)