Hallo and welcome to Anatomy Lesson #21: Smallpox. This lesson represents a departure from our usual discussions which emphasize gross anatomy. Today, we will learn about smallpox via microscopic anatomy, immunology and history! Please consider this but a brief respite from our studies of the upper limb – a topic we will return to in Anatomy Lesson #22. Outlander book readers will understand that we must make our way to the hand and very soon!

Now, how do we find ourselves learning a lesson about witches, devils and smallpox? Well, it is the machinations of that pretty little liar Laoghaire (not the actress, who is fantastic!). Yep, this 16-year-old got a witch-itch to dispose of Claire Fraser once and for all (Starz episode 111, The Devil’s Mark)! She exploited and manipulated the good and holy people of Cranesmuir to arrest, try and burn Mistress Fraser for witchcraft: she and that awful Father Bain (doesn’t he just give you the creeps?). Now, there’s a match not made in heaven!

No surprise that Geillis was accused of witchcraft being a long-time practitioner of the murky arts. And, we all kent she was something wild ever since she drank port while sporting those awesome shoon (Starz episode 103, The Way Out)! Talk about Red Shoe Diaries…for haggis sake! Takes loads of grit to don those red 18th century Christian Louboutins!

Fast forward through the trial, Claire’s skelping (ouch!) and Jamie’s bulldozer arrival: next thing Geillis pulls down her gown to reveal the devil’s mark. No more than a lowly smallpox vaccination scar (Starz episode 111, The Devil’s Mark) Geillis declares it proof that that she had lain with her master, beelzebub, and will now bear his spawn (Hum…….not a nice thing to say about Dougal!). Herself records (Outlander book):

“…It was something else I had seen that chilled me to the marrow of my bones. As Geilie had spun, white arms stretched aloft, I saw … A mark on one arm … Here, in this time, the mark of sorcery, the mark of a magus. The small, homely scar of a smallpox vaccination.”

Well, the fat is in the fire now as a gang of guys hoist Geillis off to the roasting spit! Headed for the witch’s pyre, Geillis still sports those awesome red booties: now, a girl has to look her best even if it’s for her own barbeque!

Whoa! What with all the brouhaha we shouldna forget that Claire bears her own smallpox vaccine scar! Yes, if you took the midterm practical exam (Anatomy Lesson #18) you witnessed foreshadowing: Claire’s left arm as she kisses Jamie (Starz episode 107, The Wedding). To be sure, the red arrow points to her vaccination scar proving she came from the 20th century. We book readers (not meaning to sound snooty here) already knew this scar would become an issue in future episodes. It’s good thing that neither the villagers nor Father Bain saw that scar or Claire would have been kindling!

Next, let’s study smallpox: its history, cause, signs and symptoms and the vaccination that prevents it. Hey, now wait! Please don’t haste away in fear and loathing. True, smallpox isn’t a sexy topic but it is very interesting stuff. I’ll even throw in Starz images, book quotes and historical paintings to keep you focused on the lesson. And, I’ll warn you before any gruesome pics arise (because smallpox isn’t pretty). Promise!

In Europe, smallpox was originally known as the “pox” or “red plague”. The term smallpox was first coined in 15th century Britain to distinguish smallpox (one word) from the great pox (two words). What is the great pox? Well, the great pox is syphilis, an entirely different disease, different cause, different symptoms and different treatment. Of the two diseases, however, smallpox is by far more deadly.

Sufferers of syphilis classically exhibit three stages but stage two is characterized by a non-itchy rash and hence the term “pox.” Photo A is a 16th century woodcut illustrating the rash of secondary syphilis. But, enough great pox for now; we will return to it in a future anatomy lesson.

Photo A

Back to smallpox. We’ll approach this disease in an orderly manner by following its structure, history, signs and symptoms, treatment and prevention. Warning: this lesson includes three graphic images showing sufferers with full-blown smallpox. If such images bother you, an advanced warning will allow you to skip them.

Here is your warning sign:

Here is your “it’s safe to peek” sign:

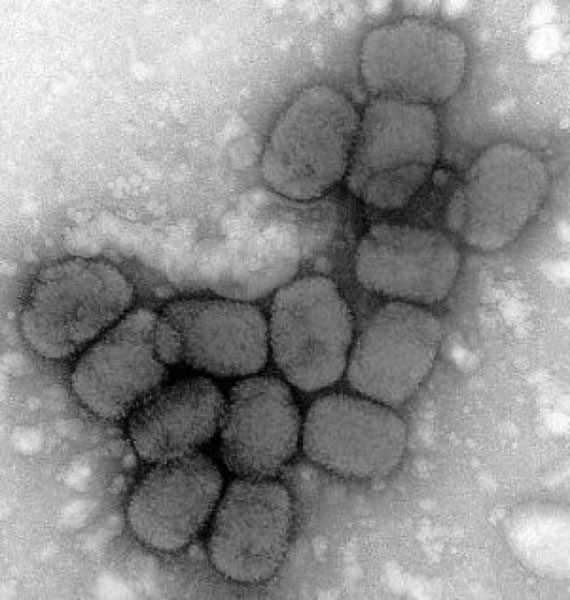

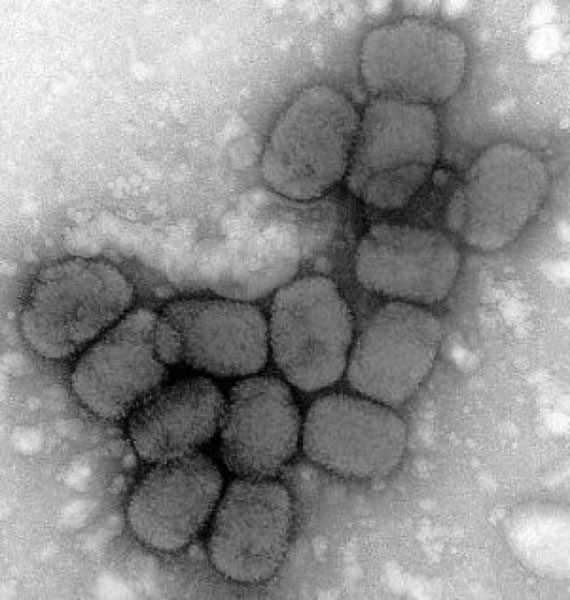

Smallpox is an acute, contagious disease which derives its name from the Latin meaning “spotted” or “pimpled” referring to raised bumps or pustules that cover skin of the afflicted. Smallpox is not caused by a bacterium (sing.) but by the variola virus a large brick-shaped member of the poxvirus family (Photo B – transmission electron microscope – TEM image).

Photo B:

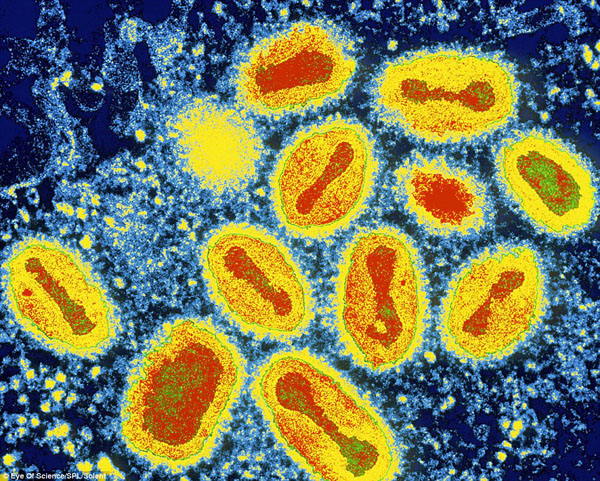

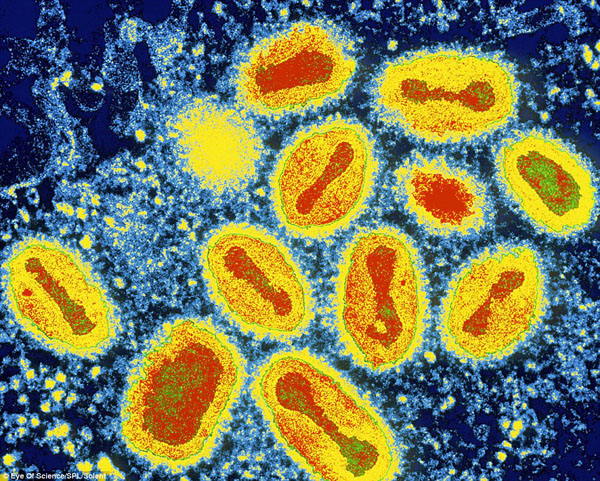

The following image (Photo C – TEM image) reveals the internal structure of the variola virus. Understand that the virus is essentially colorless – the image colors are computer generated. The red-orange dumbbells represent the complex viral core. Too technical? Then, let’s move to the history of smallpox.

Photo C

The history of smallpox is fascinating in that it altered the course of human history and even contributed to the decline of civilizations. It is no understatement to declare that smallpox ranks among the most devastating illnesses ever suffered by mankind and probably contributed to the vintage curse “a pox on thee.” Smallpox routinely killed at least one third of its victims. Sadly, the survivors of this dreadful pestilence were often left with major disfigurement or disability. Even more devastating is that governments have been known to intentionally infect groups of people with the disease to eradicate them from a desirable area. This lesson won’t be addressing those atrocities in detail but it bears mentioning because for centuries, people have known how crippling this disease is to communities.

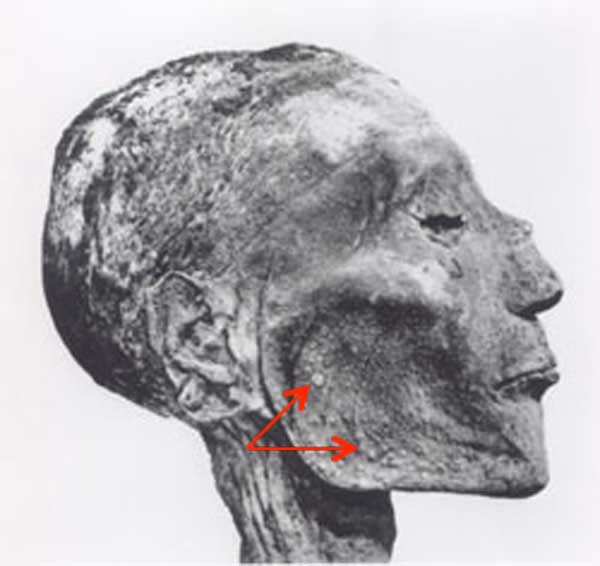

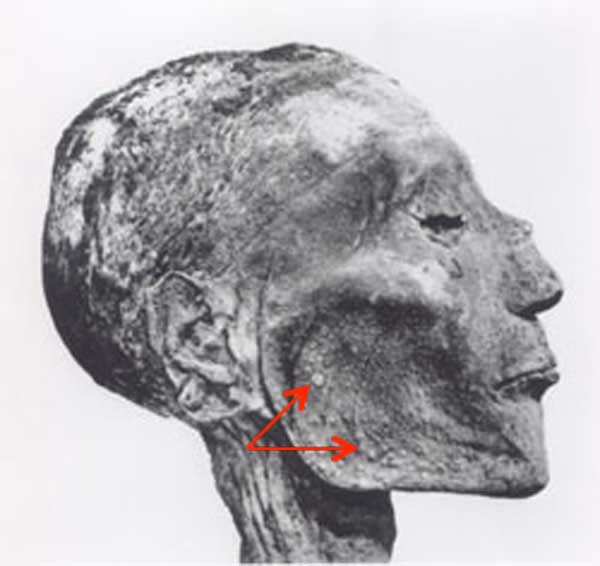

Smallpox is believed to have evolved from a rodent virus between 16,000-68,000 years ago; the wide time range is due to different estimates of genetic change during evolution, the so-called molecular clock. Evidence suggests that smallpox jumped to humans about 10,000 BCE. The earliest physical evidence of the disease comes from Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses V who died in 1157 BCE (Photo D). His mummified remains show the telltale skin pockmarks. Numerous old manuscripts record what appear to be waves of smallpox epidemics that repeatedly struck the Eastern hemisphere.

Photo D

The clearest description of smallpox from pre-modern times is credited to a 9th century (860 – 925 CE) Persian physician and scholar, Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi ( Photo E – examining a child with smallpox). Known in the West by his Latinized name, Rhazes or Rasis, he was an important figure in the history of medicine as he was the first to differentiate smallpox from measles in his text, Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah (The Book of Smallpox and Measles).

Photo E

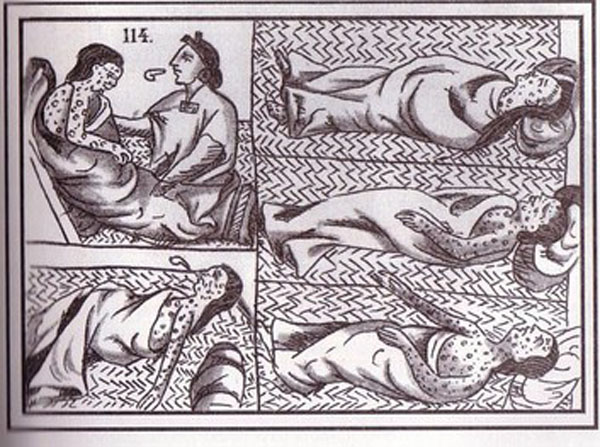

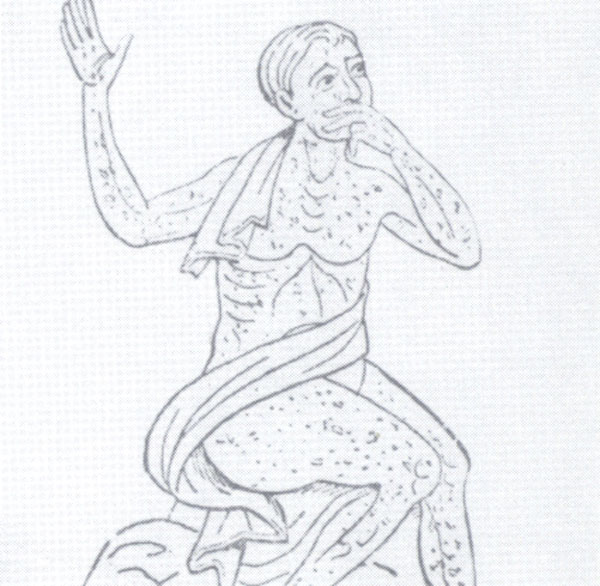

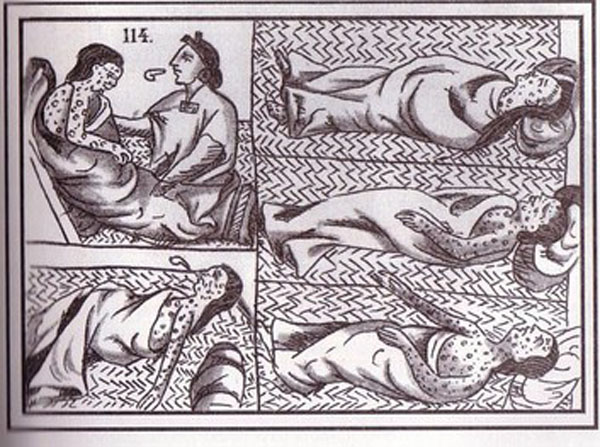

Smallpox reached Europe between the 5th and 7th centuries CE and over time spread along trade routes into Africa and Asia finally reaching the Americas in 1519 via Spanish conquistadors. Indigenous peoples had no immunity to the disease so more than three million Aztec as well as many Inca succumbed to smallpox (Photo F – 16th century woodcut).

Photo F

Moving to Jamie’s time of the 18th century, smallpox is estimated to have claimed 60 million lives including five reigning monarchs and was responsible for a third of all blindness; it also marked the faces of more than half the population of Europe.

A genuine scourge, it killed 20-60% of all those infected and over 80% of infected children died from it. Jamie’s own family suffered smallpox when he was a lad. Here from Starz episode 113, The Watch and in Herself’s own words (Outlander book):

“Two red- haired, tartan- clad little boys stared solemnly out of the frame … Jamie, and his older brother Willie, who had died of the smallpox at eleven. Jamie could not have been more than two when it was painted … Jamie had told me about Willie … I remembered the small snake, carved of cherry wood that he had drawn from his sporran to show me.”

To underscore its havoc during the 20th century smallpox killed 300-500 million people globally. In 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 15 million people worldwide contracted smallpox with two million deaths the same year.

Smallpox is spread through direct contact with infected people or their body fluids or via fomites, contaminated objects that transmit disease (e.g. bedding). As a child at Lallybroch (Starz episode 113, The Watch – image below) Jamie had smallpox but his case was not serious. Herself explains (A Breath of Snow and Ashes book):

He considered for a moment. “I had the smallpox when I was a wean, but I think I wasna in danger of dying then; they said it was a light case.

Och! Is this possible? Could Jamie have had a light case of the smallpox? Would Herself make such an error? No problemo! Indeed, there are two main types of smallpox: Variola major, the common and most lethal form and Variola minor, a milder disease which was fatal in less than 1% of cases. We can even postulate that Jamie may have been exposed to the same variant as Willie but received a lower viral load or was less susceptible to its effects. Finally, a couple of rarer forms of smallpox invariable caused death but these lay beyond our present discussion.

The signs and symptoms of smallpox are very well known. WARNING: the next three images show full blown smallpox; please skip if you must. Watch for the kitten to know it’s safe to come out again.

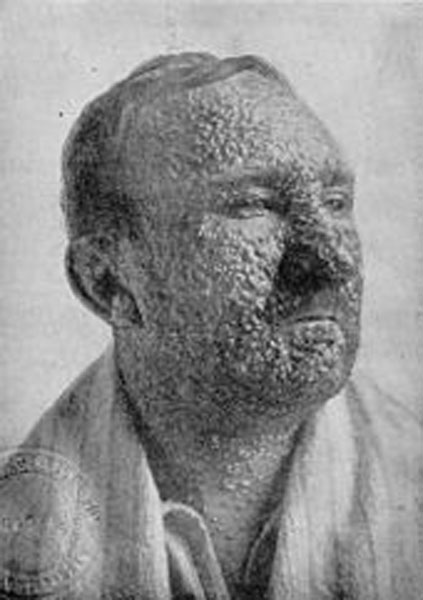

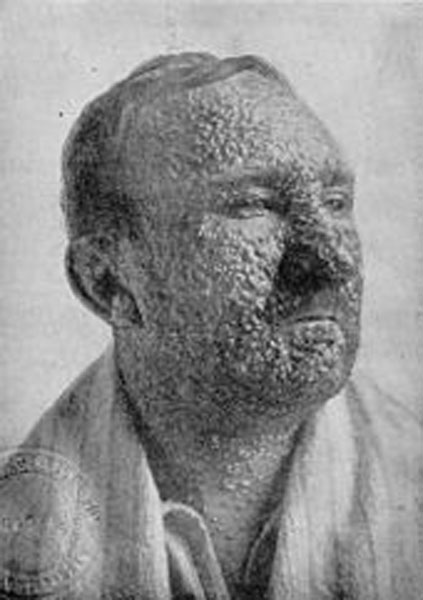

After a victim inhales the smallpox virus or is infected via fomite, it has an incubation period of about 12 days during which the infected person is not contagious. During this time, the virus is busy infecting cells of mouth, throat and respiratory tract after which it distributes to lymph nodes and other structures. Like many viruses, it produces a 2-4 day prodrome (early symptoms) of mild fever, muscle pain, malaise, headache and prostration. By 12-15 days, large numbers of virus flood the bloodstream (viremia) and the first visible lesions appear on the mucosa (Anatomy Lesson #14) of mouth, tongue, palate and throat. By days 15-17 skin eruptions occur. Although smallpox is routinely categorized as a skin disease (Photo G – 1912 archival photo) understand that it also invades most mucous membranes of the body including exposed surfaces of the eye.

Photo G

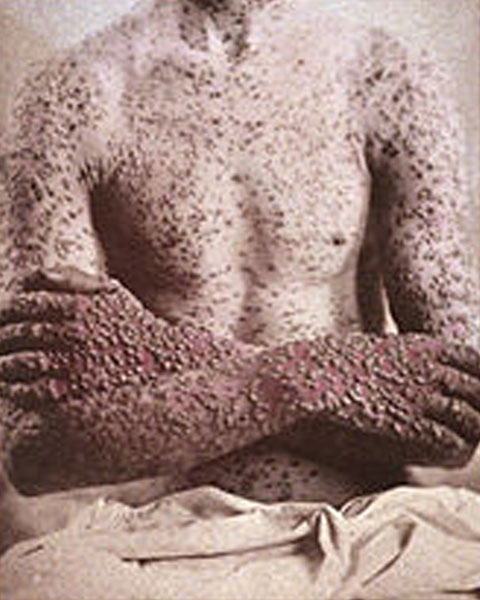

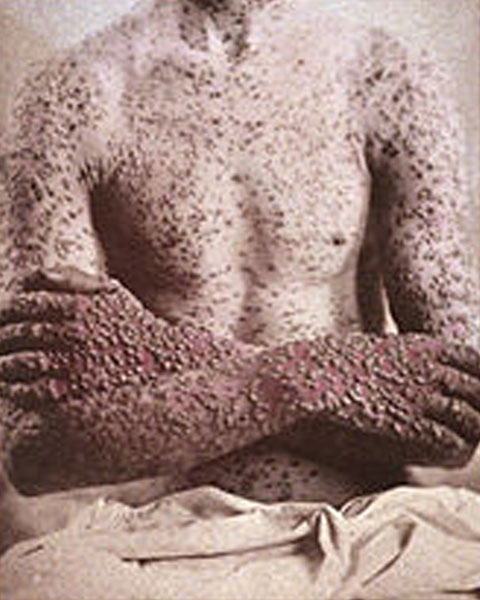

Skin eruptions rapidly develop into fluid-filled pustules: sharply raised, round, tense and firm to the touch. The pustules traverse epidermis and dermis and are umbilicated meaning they demonstrate a central pit (Photo H – 20th century). By the end of week two the pustules deflate, dry up and form crusts or scabs. By days 16–20, scabs flake off leaving depigmented (no skin pigment) white scars.

Photo H

Another defining characteristic of smallpox lesions is their distribution: pustules cover the entire body with concentrations on the head and upper and lower extremities including palms and soles (Photo I – 1886 archival photo).

Photo I

IT’S SAFE TO PEEK NOW!

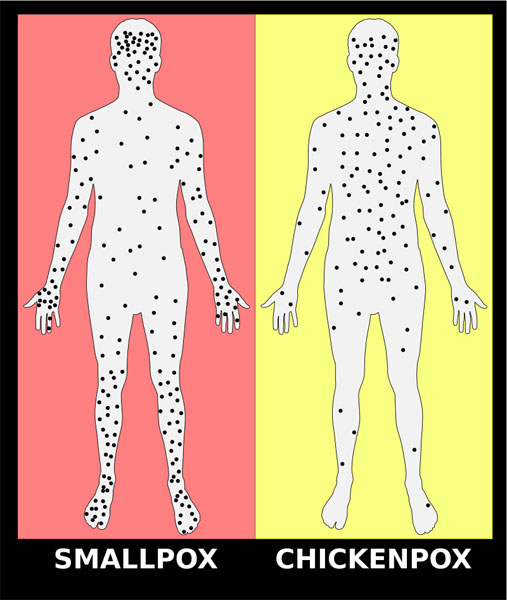

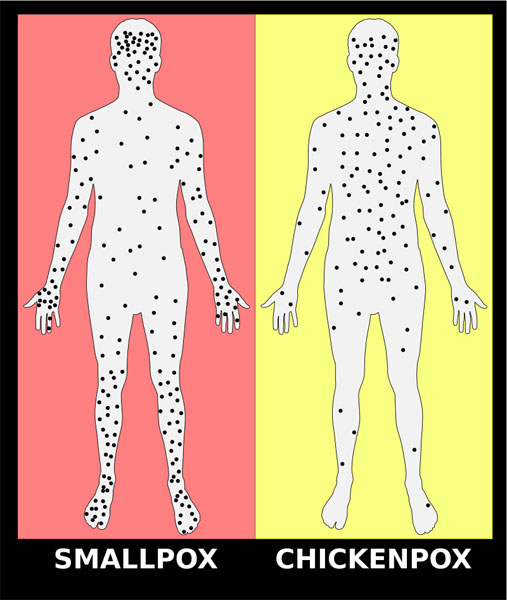

Skin distribution helps practitioners distinguish smallpox from chickenpox lesions which are concentrated on the trunk and less numerous on the extremities (Photo J). In addition, all smallpox skin lesions are of the same maturity (see Photo I) whereas chickenpox lesions present in various stages of maturity: old healing lesions intermix with new developing lesions.

Photo J

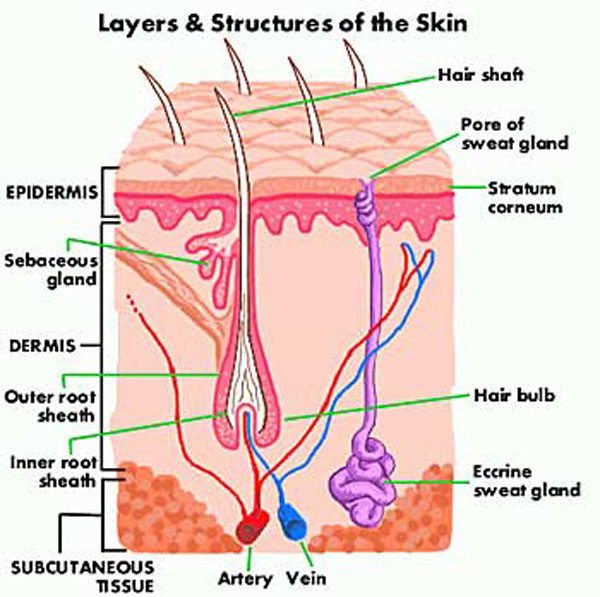

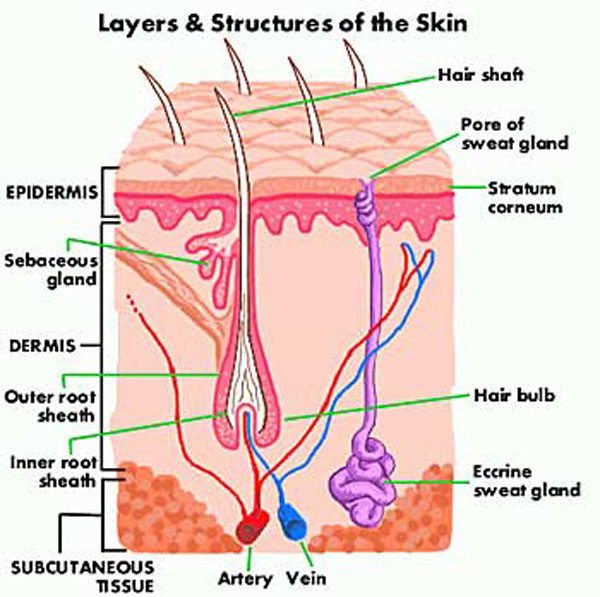

Next, let’s consider how smallpox leaves scars or pockmarks as a “gift that keeps on giving.” If you read Anatomy Lesson #5 and Anatomy Lesson #6, you learned the structure of skin and its appendages. As a quick review, skin is divided into an outer epidermis and a deeper dermis (Photo K) which in turn is bound to subcutaneous tissue (not part of skin). Skin bears a number of appendages including hairs, arrector pili muscles, sweat glands and sebaceous glands. Sebaceous glands produce sebum, a waxy-oily substance that is secreted into hair follicles or via small ducts leading to skin surfaces. Sebaceous glands are found in all skin except that of soles and palms and they are most numerous on the face. The awful smallpox lesions extended deeply into the dermis where they destroyed sebaceous glands. In the aftermath of healing, deep white scars (pockmarks) were left everywhere on the skin but were densest and most disturbing on the face, the body part by which the world identifies us.

Photo K

If an individual survived smallpox, long-term complications included pockmarks, blindness, arthritis, osteomyelitis (bone marrow infection), pneumonia and encephalitis. On the plus side and there was only one plus, sufferers typically developed immunity to subsequent smallpox outbreaks.

Many famous historical people suffered the ravages of smallpox. These include Queen Elizabeth I who in 1562 was so scarred by smallpox that she was left half bald and dependent upon wigs and heavy lead-based makeup to cover her pockmarks (Photo L – Armada portrait by George Gower). During this era, ideal beauty and wealth was marked by very pale, white skin. To achieve this look, people applied a foundation of lead and vinegar, even using mercury in makeup, which presented it’s own health problems.

Photo L

Truly a global scourge, the following is an incomplete list of famous historical figures that either died of or were disfigured by smallpox:

- Marcus Aurelius (Roman Emperor)

- Chief Sitting Bull, Lakota Sioux

- Ramses V of Egypt (20th Dynasty)

- Kangxi, Shunzhi and Tongzhi, Emperors of China

- Date Masamune, regional strongman of Japan

- Cuitláhuac, Aztec ruler of the city of Tenochtitlan

- Huayna Capac, Incan Emperor

- Guru Har Krishan, 8th Guru of the Sikhs

- William II King of Scotland/William III of Orange (same man)

- Queen Mary II

- Joseph I, Emperor of Germany

- Peter II, Emperor of Russia

- Louis XIV, King of France

- Louis XV, King of France

- Henry VIII and his family: sister Margaret, Queen of Scotland, fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, daughters: Mary I of England and Elizabeth I of England, great-niece, Mary, Queen of Scots and only surviving son Edward VI (died of smallpox complications).

- Holy Roman Empress Maria Josepha wife of Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II

- William III’s mother (lead to permanent ousting of the Stuart line from the British throne)

- William III’s wife, Mary II

- Peter II of Russia

- Peter III

- George Washington, U. S President

- Andrew Jackson , U. S President

- Abraham Lincoln, U. S President (quarantined just after the 1863 Gettysburg address)

- Joseph Stalin, Premier of Soviet Union

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Photo M – Bologna Motzart – artist unknown)

Photo M

Hey, am I losing you? Well, here, this will jolt ye awake! I said this wasna going to be a sexy lesson, but the next image shows that I, um, clearly lied. Only Jamie could turn buttering and eating a piece of bread into global cardiac arrest. Grab the paddles! Stand clear!

Now let’s turn to treatment and prevention of smallpox. First the bad news and then the good: The bad news is treatment for smallpox is minimal. A smallpox vaccination given within three days of exposure can lessen the disease but otherwise supportive therapy such as fluid administration is the order of the day. The good news is smallpox can be prevented. A brief history of its prevention follows.

The earliest procedure to prevent smallpox was variolation wherein powered smallpox scabs (ugh!) were inhaled through the nose (oh!) or pus from smallpox lesions (yuck!) was scratched into the skin. Although disputed by some, this may have been practiced in India as early as 1,000 BCE. Undisputed are accounts of variolation performed in China by the 10th century and widely practiced by the 16th. If successful, variolation produced lasting immunity to smallpox. However, it was an iffy practice because a variolated person could get full-blown smallpox from the procedure and transmit it to others. Why then was it practiced? Because variolation caused 2% mortality rate compared to 30% + mortality rate for smallpox!

The next procedure to prevent smallpox is credited to Edward Jenner (1749-1823), an English country doctor of Gloucestershire. Jenner (Photo N) was a private student and lifelong friend of the great Scottish surgeon, anatomist and naturalist John Hunter (Anatomy Lesson #3).

Photo N

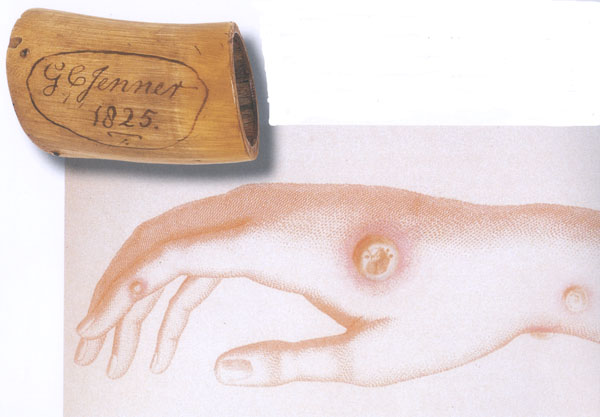

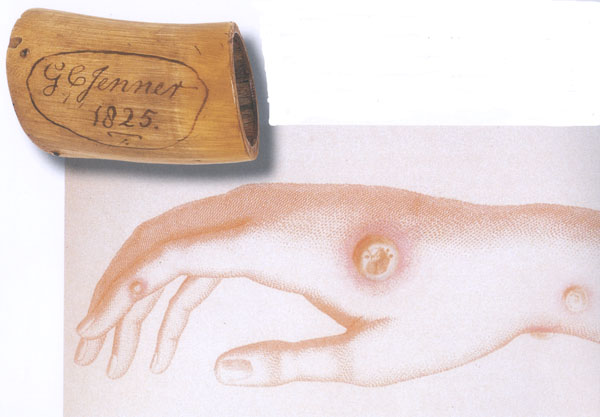

As a country doctor, Jenner heard dairymaids with cowpox pustules on their hands (Photo O) claim that they could not get smallpox: “I cannot take the smallpox, since I have had the cowpox.” Medical men of the day were aware of these claims but most dismissed them as folk lore. Jenner, on the other hand, was so intrigued he made observations and studied cowpox for over a quarter of a century. From John Hunter, he received the following famous bit of advice: “Why think? Why not try the experiment?”

Photo O

Finally in May of 1796, Jenner did the experiment: he removed “matter taken from the sore on the hand of a dairymaid” (Photo O – Sarah Nelmes) and inserted it into skin scratches on the arm of eight-year-old James Phipps, son of Jenner’s poor landless gardener (Photo P).

Are you horrified? But of course you are! In today’s western world of informed consent and scrutinized research protocols such a thing would be absolutely prohibited: different times, different rules.

Back to the story: seven days after the procedure, James experienced chills, loss of appetite and slight headache but the next day felt fine. Then on several occasions in 1796 Jenner did the unthinkable: he inoculated James with smallpox matter and the boy experienced no disease whatsoever! Jenner presented his findings to the Royal Academy, but more importantly, he had the foresight to publish them in a 1798 booklet explaining how inoculation with cowpox caused immunity to both cowpox and smallpox and thus was born the procedure later termed vaccination.

How did the vaccination work? Well, cowpox is caused by cowpox virus a poxvirus which is molecularly similar to the smallpox variola virus so the body’s immune system creates protective and memory cells that upon subsequent exposure will attack and destroy the smallpox virus.

In fairness, Jenner was not the first to inoculate people with cowpox virus to achieve smallpox immunity: others included Benjamin Jesty (farmer- Dorset, England) who performed the procedure on family members in 1774 and in 1791, Peter Plett from the Duchy of Holstein (now Germany) inoculated three children. The reason Jenner is credited with the feat is because he was the first to publish his findings as advised by the sage academic adage: publish or perish! His publication even included the drawing of Sarah Nelmes’ hand and a cupping horn in which he transported cowpox-infected matter for vaccination (Photo O).

Photo P

A wee bit more history and then we move on: In 1809, the first U.S. state began compulsory public vaccination against smallpox. England introduced compulsory infant vaccination via the 1853 Vaccination Act. Other European countries established similar programs but many were fraught with problems and rebellions by the general public.

The last and current smallpox prevention method involved switching from cowpox virus to a related virus for vaccination: Also known as vaccinia virus, this poxvirus is molecularly similar to both smallpox and cowpox and some think it may be a hybrid of the two; the precise origin of the modern vaccinia virus has become lost.

WARNING: If needles make ye queasy, ye may want to look for that kitten agin.

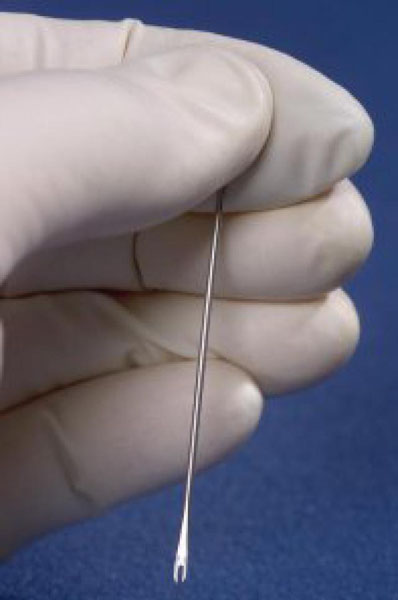

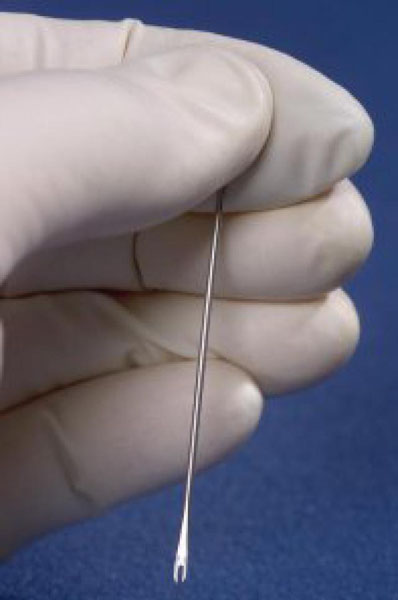

Here is how current day vaccinia vaccination is performed: The vaccine is not given with a hypodermic needle and thus is not a “shot” like many vaccinations. Rather, the vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle (Photo Q).

Photo Q

The needle tip is dipped into vaccine solution such that the prongs retain a droplet of fluid (Photo R).

Photo R

The upper arm is then quickly pricked several times with the needle (Photo S). The pricking is not deep. Did you notice I use the present tense? Yes, the vaccine is still given even today but not to the general public.

Photo S

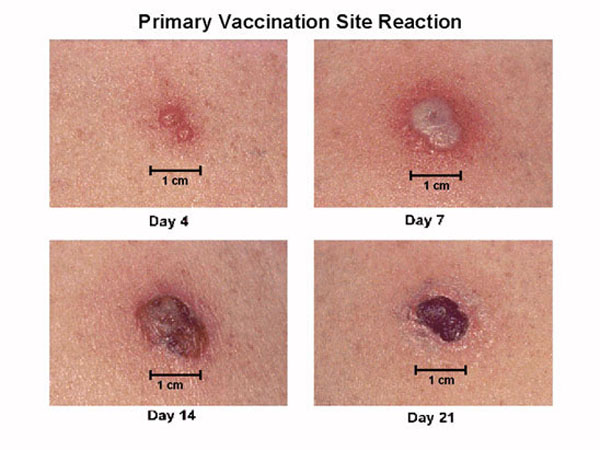

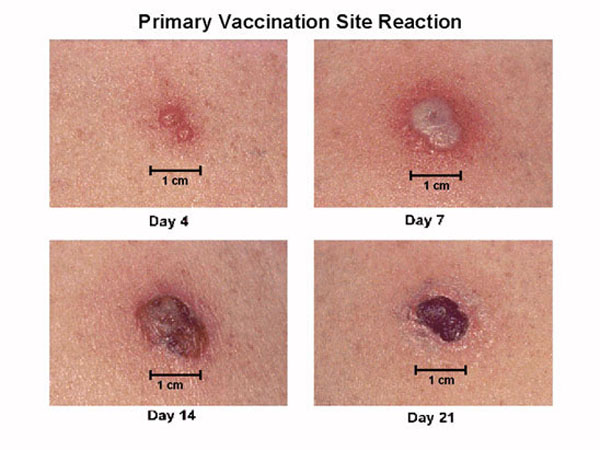

If vaccination is successful, 3-4 days later, red and itchy bumps develop at the vaccination site where the body’s protective cells (lymphocytes) react to foreign molecules of the vaccinia virus (Photo T). After a week, the bump becomes a large pus-filled blister. At week two, the blister dries up and forms a scab. The scab falls off during the third week, leaving a visible scar. The size of the scar depends on the intensity of an individual’s reaction to the vaccine.

Photo T

OK! IT’S SAFE TO PEEK NOW!

Back to smallpox history, after vigorous public vaccination campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the last recorded case of naturally-occurring smallpox was in Somalia in 1977. Three years later, WHO declared that smallpox was eradicated from the world, a feat that is generally regarded as one of the greatest triumphs of modern medicine. So officially the deadly virus no longer exists in nature!

Personally, I cringe when humans make sweeping statements about nature as they evoke the follies of human hubris. Claire reflects on such an issue in The Fiery Cross (book 5 of Outlander series):

“This was in fact likely. However, I was quite aware of the old adage— “Man proposes and God disposes” … ” (From the Latin text by Thomas à Kempis: For man proposes, but God disposes; neither is the way of man in his own hands.”)

OR

In the more colorful words from Scottish poet Robert Burns in his 1785 poem “Tae a Moose, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest with the Plough: The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men Gang aft agley.”!

OR

In the words of Professor Ian Malcolm from the film, Jurassic Park: “Life finds a way.”

Will smallpox stay buried for good? We certainly hope so!

Let us end this lesson with more fun and games: we return to our hero and heroine in Starz episode 111, The Devil’s Mark. I love the trial wherein Jamie and Claire together witness Geillis’ confession. Take a gander at Claire’s glass face!

Oh, my! Jamie watches as Geillis exposes her “mark of the devil” and Claire suddenly kens that Geillis is a 1968 time traveler and her “devil’s mark” is naught but a lowly smallpox vaccination scar!

But, here is the moment of truth! Jamie’s nimble brain is churning fiercely as he realizes that Geillis has given him the chance to hie Claire out of that bloody inquisition. RUN! Wow. Jamie’s eyes could act all their own only that would be gross so…never mind…but ye ken what I mean! So expressive!

After getting Claire away from Cranesmuir and into a quiet wooded area, Herself records Jamie’s reaction (Outlander book):

“I said before that I’d not ask ye things ye had no wish to tell me. And I’d not ask ye now; but I must know, for your safety as well as mine.” He paused, hesitating. “Claire, if you’ve never been honest wi’ me, be so now, for I must know the truth. Claire, are ye a witch?” I gaped at him. “A witch? You— you can really ask that?” … “Yes, I am a witch! To you, I must be. I’ve never had smallpox, but I can walk through a room full of dying men and never catch it. I can nurse the sick and breathe their air and touch their bodies, and the sickness can’t touch me. I can’t catch cholera, either, or lockjaw, or the morbid sore throat. And you must think it’s an enchantment, because you’ve never heard of vaccine, and there’s no other way you can explain it.”

With her vaccination scar clearly on display, Claire tearfully explains her own “devil’s mark” to Jamie.

Jamie (this man is a true wonder) does believe her and her heart; he kens she is telling him the truth and pledges that he will believe whatever she tells him. So, she tells him everything from the get-go including stone travel, combat nursing and boring Frank! Yikes! And all’s well that ends well for oh, say, two hours. Nice job to the entire cast and crew for that mind-numbing, stomach-rolling, breath-holding, teeth-grinding rollercoaster ride!

However, honesty compels me to declare the true devil’s mark from Starz episode 111. Who is nominated for this honor? Drum roll!!!! And, the winner is: the puir, misunderstood little gal Laoghaire. Who is this bonny lass with more facets than a well-cut stone? Watch her face change as she hisses at Claire!

A daughter accused by her own father of loose behavior?

The innocent “virginal” seductress of love-of-her-life Jamie?

The darling, needle-wielding granddaughter of Mrs. Fitz?

The cunning author of Claire’s imprisonment and verdict?

Or, a tiny dancer who will gladly execute (so-to-speak) a pirouette atop Claire’s ashes?

Hope ye all ken by now that if Starz episode 111 has a devil’s mark it surely is this calculating, cunning and cruel Bad-Lass!

Ending on this somber note of justice gone awry, I do hope you all learned something new today: “Let’s rise and be thankful, for if we didn’t learn a lot today, at least we may have learned a little…” (Born for Love: Reflections on Loving, Leo Buscaglia).

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Image creds: “Great Moments in Medicine”, 1961 paintings by Robert A. Thom, “Medicine: Perspectives in History and art, www.bioteach.unl.edu, www.crateandbarrel.com, www.dailymail.co.uk, www.dermatologyabout.com, www.healthline.com, www.mayclinic.org, www.ncbi.nim.nih.gove, www.who.int, www.wikimedia.com, www.wikipedia.com, www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com, www.2.lbl.gov, www.socialphy.com, www.momentummoonlight.com.