Claire has been poisoned! Learn more tomorrow in Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach – Wobbly Wame!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Human Anatomy taught through the lens of the Outlander books by Diana Gabaldon and the Starz television series

Claire has been poisoned! Learn more tomorrow in Anatomy Lesson #46, Splendid Stomach – Wobbly Wame!

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

Greetings Outlander anatomy students! Our last Anatomy Lesson #35 covered wounds and injuries featured in both Outlander book and the Starz series. Today’s Anatomy Lesson #36 continues with this theme because there are still lots of Outlander owies to uncover and discover!

WARNING: A Spoiler from Outer Space appears at the end of this lesson in the form of an image, a question, and a wound description from 20th Century FOX’s “The Martian.” The image of a scaredy cat appears just before the Space Spoiler. If you haven’t seen the film, you may want to skip it. You may wonder why this movie appears in this lesso … why to apply what we learned from the lessons on wounds and injuries!

During the last lesson we learned that the science of pathology is the study of abnormal anatomy and that it provides a sane classification of wounds and injuries. Anatomy Lesson #35 covered types of mechanical trauma so today’s lesson will pick up where we left off. We will study all but the last seven items on the following list:

Once again, examples from Diana’s books and the Starz Outlander series will serve as our anatomical models for the above injuries.

Wounds and injuries are serious topics, so let’s lighten this lesson with a wee bit of humor. Anatomy Lesson #35 featured a laceration inflicted by a boar’s tusk. The lesson stated that boars can run up to 40 k/hr! Don’t know if the following baboon taxi cab qualifies as a true boar but it is likely close. Watch this with sound. I dare you not to laugh!

https://www.instagram.com/p/5wwgkECXpq/

First up are a mess of Thermal Injuries, including thermal burns, hyperthermia, chilblains, hypothermia, frostbite, and electrical injury. Thermal injuries are the result of excesses in temperature: too much heat or to much cold.

As an aside, electrical injuries do fall into this category. Electricity may pass through the body without effect, it may produce cardiac arrest, or tissues may be burned. But, no electrical burns in the 18th century for us to consider.

Thermal Burns: Heat, electricity, chemicals, or radiation exposure cause thermal burns. Typically, these are classified as first, second or third degree types and occasionally we hear of fourth degree burns, but did you know there are also fifth and sixth degrees?

Some of you will recall Anatomy Lesson #5 and Anatomy Lesson #6 where we learned that skin is composed of epidermis, the surface layer of skin cells, and dermis, the underlying and supporting connective tissue layer. Another useful way of considering thermal burns is to describe their depth relative to epidermis and dermis.

Partial-thickness Burn: This type of burn damages either the epidermis or both epidermis and outer dermis and includes first and second degree burns. Such burns are red and often blister. The skin tends to blanch under pressure and the burns are very painful. Most partial-thickness burns heal without scarring because hair follicles are spared and each surviving follicle includes a sleeve of epidermis (Anatomy Lesson #6); the sleeves regenerate to help cover the damaged surface. However, if a partial-thickness burn is deep and/or large, then optimal healing may require a skin graft. Infections also complicate the healing of a partial-thickness burn and increase the likelihood of scarring.

So, consider the next Outlander image. Here, gracious Nurse Claire gently applies a healing balm to Mrs. Fitz’s right forearm (Starz episode 110, By the Pricking of My Thumbs) which received a partial-thickness burn courtesy of the “puir ovens” at Castle Leoch. Red and painful (she flinches at Claire’s touch) this burn should heal without scarring as long as infection is kept at bay.

Full-thickness Burns: Full-thickness burns differ from partial thickness in that they extend through the epidermis, the entire dermis and into underlying tissues. Hair follicles are destroyed so they cannot contribute to epidermal regeneration. The skin of such burns is stiff and leathery and may be charred; the color may be pink, white or brown. Such wounds do not blanch under pressure. They are typically aesthetic (painless) because the skin nerve endings are destroyed although the rim of such a burn is painful where nerve endings often survived. Full-thickness burns include third, fourth, fifth and sixth degree burns which extend into underlying fat, muscle, ligaments and even bone. Fourth degree burns may require amputation. Fifth and Sixth degree burns are usually fatal. Horrific injuries!

We witness a full-thickness, third degree burn (Starz episode 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul) as the masterful monstrous madman demands a traumatized Jamie brand himself with BJR’s wax seal – JR indeed! This despicable act produces a brown, dry and leathery full-thickness burn of Jamie’s left side but not over his heart as Jack-Rat demands.

Excision is the only way to deal with this injury and Murty is our man! With a dirk quick-flick, Murtagh extracts the branded skin. Jamie belongs to Claire! ‘Nuf said.

Grand, garrulous Godfather then casts JR into the fiery pit where he belongs! Tweet: #JRburnsinhell! Couldn’t happen to a more deserving guy. Buh-Bye BJR!

Thermal Cold Injuries: Cold temperatures cause thermal injury because the human body is poorly equipped to regulate and prevent heat loss; this is especially true of children and the elderly. Normally, fat deposits and heart, blood vessels, brain, skin, and muscles help combat cold effects either by insulation or by initiating responses such as shivering, redirecting blood flow from surface to vital organs, and reducing energy consumption. But exposure to cold temperatures over long periods overcomes our coping mechanisms and produces a range of thermal cold injuries such as chilblains, trench foot, hypothermia and frostbite.

Chilblains: Also known as pernio, chilblains is a 16th century term for painful, red and itchy swelling of the skin as the result of repeated expose to cold but not freezing air (Image A). Ouch, that looks sore! Digits are most commonly affected because blood circulation to the limbs is typically reduced during cold exposure.

Chilblains usually clear up with warmer weather and resolve without permanent damage unless infection occurs. Severity can be lessened or eliminated by wearing warm clothing over exposed skin, limiting exposure to cold, and applying lotions to ease the affected parts.

Episodes from season one of Starz Outlander do not feature chilblains. But have no fear, our amazingly witty and resourceful Diana writes about them in her second book, Dragonfly in Amber, wherein Claire treats some imprisoned men. She’s a wonder! Which “she” do I mean? Take your pick. Hah!

I talked my way into the cells of the prison, and spent some time in treating the prisoners’ ailments, ranging from scurvy and the more generalized malnutrition common in winter, to chafing sores, chilblains, arthritis, and a variety of respiratory ailments.

Image A

Hypothermia: Hypothermia is a systemic condition brought on by a decrease in core body temperature (<98.6° F or 37° C) as a result of extended cold exposure. Symptoms of hypothermia include a drop in core temperature, vigorous shivering, confusion, sleepiness, slurred speech, shallow breathing, weak pulse, low blood pressure, changes in behavior and slow reactions. The victim exhibits the “umbles” meaning grumbles, mumbles, stumbles and fumbles because cold affects muscle and nerve function. If the core temperature drops to 90º F (32.2º C), then bradycardia (slow heart rate) and atrial fibrillation (fast and irregular contraction of the heart’s upper two chambers) may ensue. During the process, the entire body responds by increased heat production due to hormone release, re-routing blood to core organs, and shivering. Unfortunately, these responses expend considerable energy and cannot be sustained for long.

Hypothermia may well be a factor in Starz episode 110, By the Pricking of My Thumbs, as Claire is moved to save a sick infant after being abandoned by its parents. Here from Outlander book:

She hastily snatched the baby from my arms, then laid it back where I had found it, in a small depression in the rock…“But it’s sick!” I protested, stooping toward the child again. “Who would leave a sick child up here by itself?” The baby was plainly very ill… I wondered that it had had the strength to cry… “It’s only a sick child. It might very well not survive a night in the open!”

Alas, a small infant has little body fat to help insulate it against cold temperatures. And, an ill infant will not have the strength to initiate the other protective mechanisms mentioned above. Poor little one; Claire’s loving heart broke when her healing powers couldn’t affect the outcome of this sad event.

Frostbite: Frostbite is a type of cold injury in which the body’s shell is exposed to freezing temperatures; it affects mostly feet, hands, noses and ears. Superficial frostbite begins with the sensation of extreme coldness, followed by numbness. Ice crystals form in the tissues and fluid leaks from blood vessels forming clear, fluid-filled blisters. More severe frostbite is marked by blisters that accrue a purplish fluid and, later, blood begins to clot.

Do we see examples frostbite in Outlander? Maybe so, maybe no. The first season brought us snowcapped Munros (Starz episode 105, Rent) and a skirmish in the snow between Murtagh and Jamie as they rescue wee Willie from Rupert.com (Starz episode 109, The Reckoning).

Speaking of snowcapped peaks, the nearest evidence of Outlander frostbite arrives in the form of goose bumps (snort) on a pair of bodacious tatas. Now, goose flesh doesn’t really qualify as frostbite, but its the best I can do for it, ye ken? Arrector pili muscles (Anatomy Lesson #6) pucker the skin by uprighting the hairs on Mistress Laoghaire MacKenzie’s chest! Almost but not quite shivering, the teenage bad-lass devises a meet-and-greet at Jamie’s secret place wearing little else than a daring corset (where the heck did she get that?)! Best get that cloak back on lest ye suffer thermal burns from a willow switch wielded by grandma Fitz! Mayhap your da should have had his way about that hiding in the hall? Burrr!

Here’s some exciting thermal news: an arm of the US Department of Energy is developing clothes with thermal properties that adapt to the environment and to the wearer’s body. By changing their make-up or shuttling heat to and from the body, the garments can keep people comfortable whatever the external temperature (30 January 2016, New Scientist). I’m ready for one of these jackets, how about you?

Alcohol Injury: Alcohol is a colorless, volatile, and flammable liquid that is the intoxicating element of wine, beer, and other spirits (duh!); it is also used as a fuel and is an industrial solvent! Not surprisingly, alcohol is also the most widely used and abused toxic agent in the world. Not meaning to preach as I have a wee nip here and there too, alcohol injury ranges from binge drinking to full on alcoholism with a myriad of accompanying ailments.

Claire offers a very succinct analysis of alcohol here, in a quote from “The Drums of Autumn:”

“Alcohol isn’t a good anesthetic at all,” I said, shaking my head. “It’s a poison. It depresses the central nervous system. Put the shock of operating on top of alcohol intoxication, and it could kill him, easily.”

And, there we have it in a nutshell. What a woman!

Here’s how the body handles alcohol: the stomach lining contains gastric alcohol dehydrogenase (GAD), an enzyme that metabolizes alcohol. The liver is also equipped with alcohol dehydrogenase plus other enzymes that help augment alcohol break down. But, bad news for the lassies: women naturally have lower levels of GAD than men and often develop higher blood alcohol levels after drinking the same quantity of alcohol.

Alcohol consumption is a complex subject but for our purposes, there are three types to consider: alcohol dependence syndrome, acute alcohol intoxication, and alcohol intoxication.

Alcohol dependence syndrome (alcoholism) is a condition characterized by long-term alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse that result in specific physiological and behavioral problems. The entity includes ten or so different signs and symptoms, but from a medical standpoint, only two are required for diagnosis. Colum, who requires major quantities of strong drink to quell his physical pain, is an excellent Outlander example. For more info, enter “alcoholism” into your search engine and pursue.

Acute alcohol intoxication (ACI) occurs when a person drinks too much, too quickly resulting in dangerously high concentrations of alcohol in the blood stream. Depressed respiratory rate, altered gag reflex, stupor, and coma are characteristics. ACI is considered a medical emergency because it can lead to coma and death. Guidelines exist about the amount of alcohol the liver can metabolize per hour and these rates should not be exceeded. Again, please get informed if this is an issue in your life.

Now, Jamie isn’t in the throes of ACI at Lallybroch (Starz episode 112, Lallybroch). Naw, he is just stinking drunk (see next category). This is just a chance to show him wearing that grand leather coat that belonged to his da’!

Alcohol intoxication (drunkeness) include symptoms of impaired physical and social behaviors such as reduced social inhibitions, euphoria, and loss of balance. Now, feisty Angus is very good example of alcohol intoxication, although he is probably one of those hearty Scottish souls who has developed a tolerance to its effects. Emboldened by Claire’s “Spanish port” and valerian root mixer, he is having a grand old time at the Gathering (Starz episode 104, The Gathering).

Herself describes the general mood at the Gathering in Outlander book:

There’s not a man in the place who’s not half in his cups already, and they’ll be far gone in an hour…The men in the Hall were rioting, dancing, and drinking, with no thought of restraint or control.

A final note about alcohol: Last month, chief medical officers of the UK issued new guidelines suggesting that there is no safe limit to alcohol consumption and advising that no one exceed 14 units of alcohol per week (16 January 2016, New Scientist). One unit of alcohol is equivalent to a standard glass of wine (175 ml or 6 oz). I must confess that 14 glasses of wine per week seems more than generous to me!

Pressure Injuries: Pressure injuries include blast injuries, decompression sickness, and high altitude illness. I’ll bet that you all don’t think there are any pressures injures in Season one of Outlander, but, there are!

Blast injuries: This type of pressure injury is caused by explosions resulting in multi-system, life-threatening injuries. These are divided into four categories:

I spy a SBI (Ha! that rhymes.) in Starz episode 109, The Reckoning, Jamie’s band of merry men creates a blast that engulfs redcoats at Fort William (Angus says it was Murty who set the charge). Plainly, these soldiers suffer SBIs because they are stuck by flying, fiery debris. Hope this makes sense.

Pressure waves from the blast also effect Jamie and Claire (Starz episode 109, The Reckoning). But, on a parapet and away from the blast, they experience a PBI. Here, the sound track briefly reflects a dulled sound and slight ringing tone. This clever device conveys to the viewer that the blast temporarily effected their tympanic membranes and inner ears (Anatomy Lesson #24)!

Decompression Sickness (DCS): This injury occurs when individuals are exposed to high air pressures and then depressurize too rapidly. Deep-sea divers or underwater workers who spend long periods in pressurized tunnels or caissons (large, water tight containers) are at risk. Flying in unpressurized aircraft and space walks may also cause DCS. Type I or simple DCS involves skin (Anatomy Lesson #5 & Anatomy Lesson #6), musculoskeletal, and lymphatic systems. Type II or serious DCS extends to lungs, brain and spinal cord (Anatomy Lesson #10). DCS can be avoided by following a slow decompression process.

Here’s how DCS works: Under high pressure, inert gases (nitrogen and others) dissolve in the blood. As a person returns to normal pressure, the inert gases come out of solution in the lungs via a process known as “outgassing.” If depressurization occurs too quickly, then the dissolved gases come out of solution too quickly and bubbles form in the blood or in the solid tissues of the body with the following results:

Starz Season One of Outlander doesn’t really show examples of DCS. The closest we can come to this type of pressure issue is rapid pressurization. Recall Jamie’s and Claire’s “leap of faith” into the icy waters surrounding Fort William (Starz episode 109, The Reckoning)? There they go! Wheeeee!

Down, down, down they go; where they stop nobody knows. Truthfully, they couldn’t sink deep enough or stay under water long enough to worry about DCS. Just messing with you!

Genetic Derangements: This category embraces a broad range of diseases based on gene defects. Several organizations devoted to genetic support and research posit that more than 6,000 genetic disorders can be passed down through the generations. Many of these are either fatal or severely debilitating.

Once again, Outlander book comes to our rescue wherein Claire encounters a genetic disease of the 18th century (Starz episode 102, Castle Leoch)!

“At the moment, though, my discomfort arose from the fact that the beautifully modeled head and long torso ended in shockingly bowed and stumpy legs. The man who should have topped six feet came barely to my shoulder. ….. ‘I welcome ye, mistress,’ he said, with a slight bow. ‘My name is Colum ban Campbell MacKenzie, laird of this castle.’ ”

Later, Claire diagnoses Colum as suffering from Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome, a genetic disease of bone, cartilage and other connective tissues (Anatomy Lesson #27). Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was a famous 19th century painter, printmaker, illustrator and draughtsman. He was the child of an aristocratic French family whose parents were first cousins. By 14, Henri had fractured both femurs and his legs ceased to grow such that as an adult, he stood 4’ 8” (1.42 m).

In 1962, a pair of French physicians described the genetic disease, pycnodysostosis (Greek meaning dense, defective condition of bone) or Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome. A child with this disease receives a recessive gene from each parent, an outcome more likely if parents are closely related. However, positive diagnosis requires genetic testing. Because genetic testing was unknown during Henri’s lifetime, it is surmised that he suffered from pycnodysostosis.

Impossible as it seems, pycnodysostosis/Toulouse-Lautrec sufferers fail to make a single enzyme (Cathepsin K – Anatomy Lesson #27), but one that is essential for bone repair and remodeling. Life long accumulations of bone injuries that cannot heal properly cause the signs and symptoms of this sad disease. Puir Colum. Little wonder he has an affinity for the rhenish!

Epigenetics: Now for something truly fascinating! For decades scientists have thought that our cells faithfully follow the genetic road map which is set at conception (12 Dec. 2016, New Scientist). However, there is growing evidence that external or environmental factors may switch genes on and off or affect how cells read genes so they may not be bound to exactly follow the DNA road map. This controversial field is epigenetics. A recent Danish study showed a link between men’s weight and gene activity of his sperm which could leave his offspring predisposed to obesity (12 Dec. 2016, New Scientist). In another study, South American guinea pigs were able to tweaked their genes to beat increased environmental heat (9 Jan. 2016, New Scientist).

Poisons: Poisons are substances that, when absorbed, inhaled or consumed, cause illness or death of living organisms. Paracelsus (1493–1541), the father of toxicology, once wrote: “Everything is poison, there is poison in everything. Only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” Paracelsus was pretty much right as a great many substances do harm in the right amounts. Even pure water can potentially harm us if imbibed in sufficient quantity.

Manufactured Poisons include many improperly used household agents and meds: cleaning agents, laundry products, pain meds, vitamins, antihistamines, pesticides, antimicrobials, sedatives, anti-depressives, cosmetics, cardiovascular drugs, etc. There are also a variety of natural poisons that nature gifts us!

Geillis Duncan kent a thing or two about poisons, enough to gradually do in her hubby, Arthur Duncan, procurator fiscal for Cranesmuir parish. Herself enlightens us in Outlander book:

“Cyanide?” He looked down curiously at me. “What’s that?” “The thing that killed Arthur Duncan. It’s a bloody fast, powerful poison. Fairly common in my time, but not here.” I licked my lips meditatively.

“I tasted it on his lips, and just that tiny bit was enough to make my whole face go numb. It acts almost instantly, as you saw… I imagine she made it from crushed peach pits or cherry stones, though it must have been the devil of a job.”

Cyanide prevents cells from using oxygen. If this happens, cells die. If inhaled, cyanide causes seizures, apnea (temporary cessation of breathing), cardiac arrest and death.

Puir Arthur, Geillis says he isn’t much to look at, but still, he had a good house and a good position; what else could a wife want? How about Jamie? Harhar! Arthur probably thought of exotic Geillis as his trophy wife!

This quote from Outlander book explains the ghastly symptoms of cyanide poisoning:

… I could see the rotund form of Arthur Duncan on the floor, limbs flailing convulsively, batting away the helpful hands of would-be assistants… The stricken man dug his heels into the floor and arched his back, making gargling, choking noises. … His jaws were clamped and rigid, though, lips blue and flecked with a foamy spittle that didn’t seem consistent with choking… The eyes were rolled back now, and the drumming heels began to slacken their beat. The hands, clawed in agony, suddenly flung wide… The sputtering noises abruptly ceased, and the stout body went limp, lying inert as a sack of barley on the stone floor.

BTW, Claire (Diana) is right! The pits of apricots, peaches, cherries and plums along with the seeds of apples contain small amounts of cyanide. So, to be on the safe side, it is best not to eat broken pits or chew apple seeds. I’m thinking about Jamie’s habit of thriftily consuming apple cores. No worries though, not enough in a core to do him any real harm.

Toxins: Toxins are compounds that cause disease and are produced by fungi, plants or animals. These include mycotoxins (produced by fungi), phytotoxins (produced by plants) and animal toxins (produced by animals – again duh!). Understand that dose is important; a small amount of a toxin may produce reversible injury, whereas larger doses of the same toxin might result in ether instantaneous death or slow irreversible injury leading in time to death.

Do we see any natural toxins at work in Outlander episodes? Aye, indeed we do! Remember that cutie nephew of Mrs. Fitz? Yep, talking about Tammas Baxter! He is ill unto death when Claire reaches his bedside (Starz episode 103, The Way Out). She hypothesizes that he was poisoned after eating the berries of Convallaria majalis or lily-of-the-valley. Weel, dinna fault him, the plant looks a lot like wood garlic!

Lilly-of-the-valley is a woodland flowering plant that is native to the Northern Hemisphere and all parts of the plant contain poisonous phytotoxins. Ingested even in small quantities, Convallaria induces abdominal pain, vomiting, reduced heart rate, blurred vision, drowsiness and red skin rashes.

Nurse Claire to the rescue! She carefully administers a decoction of bella donna (Italian for beautiful lady). Prepared from the leaves and roots of the deadly nightshade plant, the decoction contains natural atropine which, interestingly enough, is also a phytotoxin. Claire uses bella donna to counter the effects of Lilly-of-the-valley, as a muscle relaxant, to dilate the pupils (Anatomy Lesson #31), to correct an irregular heart beat and to counter other actions on the autonomic nervous system (read about the ANS in Anatomy Lesson #31). In case you were wondering, a decoction is the liquor obtained from crushing, boiling and/or concentrating the substances of a plant. Halleluah! Tammas is saved!

Venom: Venom is a form of toxin made by animals. Unlike poisons which are inhaled, consumed or absorbed, venom is injected into victims via bites, stings or other sharp body features (e.g. spines). So, insects (wasps, bees), spiders, scorpions, sea urchins, fish, snakes, and a couple of mammals produce venom although the method of injection varies widely. Outlander season one didn’t have any venom injuries but Jamie succinctly and accurately compares venom and poison in Diana’s fourth book, Drums of Autumn:

“Venemous,” Jamie corrected him. “If it bites you and makes ye sick, it’s venemous; if you bite it and it makes ye sick, it’s poisonous.”

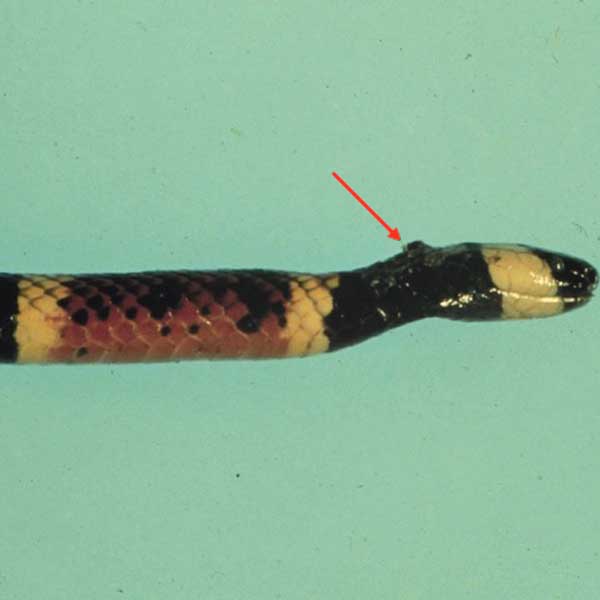

No venomous creatures in Starz Outlander series, yet! But next is a venom issue from my own archives. The non-venomous king snake and the venomous coral snake are both endowed with red, black and yellow bands (North America only). Hum, then, how can you tell one from the other? Helpful ditties exist to determine whether such snakes are friend or foe. This is important should you encounter a coral snake because it chews its venom into the victim and that venom is a powerful neurotoxin that paralyzes the intercostal muscles (Anatomy Lesson #15) which are necessary for breathing!

One ditty goes “Red and yellow, kill a fellow; red and black venom lack” or “Red and yellow, kill a fellow; red and black friend of Jack.” Huh? Black Jack has no friends! Well, maybe a snake or two… “birds of a feather” and all that! The ditties mean that if red and yellow bands touch, then it is a coral snake (keep back!) but if red and black bands touch, then it is a king snake (safe).

So, is image B that of a coral or a king snake? You got it right, it is a (Texas) coral snake! Now, do you see a slight break in the black banding pattern (at the tip of the red arrow)? That is where I killed it with a shovel. OK, OK, before you get mad at me, I am usually benevolent towards “all creatures great and small.” I don’t like killing things, but this snake was in my back yard crawling through the flower beds around the foundation of my house and they can be territorial!

Just so you are all aware, coral snakes from the Old World have variable banding colors so the above ditties are not reliable for coral snakes outside North America.

Image B

Whew! The list of injuries and wounds for today’s lesson is done. However, as promised…

SPOILER ALERT: All Scaredy Cats should stop reading now as The Martian pop quiz is next! Now, in case you wonder what The Martian has to do with Outlander, it gives us the opportunity to apply the lessons we have learned from Diana’s books and Starz series to other settings. After all, if you can’t use the anatomy, why bother to learn it? Aye?

We haven’t had a pop quiz in a very long time, so grab a pencil and paper, it’s Quiz time! Turning from Outlander to Outer Space, let’s consider the film “The Martian”, another fabulous nail-biter from film director, Ridley Scott. Mark Watney, played by Matt Damon, suffers a traumatic wound during a horrific Mars storm. Harkening back to Anatomy Lesson #35, what type of wound did he suffer? The correct answer is (hint: there may be more than one possible answer):

If you chose D. Laceration, a gold star for you!

If you chose E. Projectile a gold star for you!

But, if you chose both D. Projectile and E. Laceration, then two gold stars for you!

Here’s why both answers are best: During the brutal storm, Mark is struck by an airborne antenna dish and swept away. Receiving electronic data that he is dead, fellow crew members are forced to flee the planet, post haste. After Mark regains consciousness, he finds himself alone with a thin metal shaft embedded in his anterior abdominal wall (Anatomy Lesson #16). This is Answer D, the projectile.

Does Mark immediately panic and pull out the projectile? No, he does not because Mark is a scientist who clearly read Anatomy Lesson #35 (haha!) and knows that a projectile should not be removed in the field! He makes his way into the Mars habitat and finds its medical station and supplies. There he assesses the damage and removes the projectile himself as no medical team is hanging around. The metal projectile leaves a ripped and torn wound through the abdominal wall; this is Answer E, the laceration. The tip of the projectile has broken off in the wound, so Mark anesthetizes the flesh around the wound and with surgical instruments and a mirror, removes the embedded tip and closes the wound with staples. Luckily for Mark, there was no bowel perforation or things would have gone south very rapidly. Way to go Mark! Good lad!

How did you score? Hope you did very well on the quiz!

Our next lesson will be on wound healing and scars!

A deeply grateful

Outlander Anatomist

Photo creds: Starz, Kumar, Abbas and Fausto, 7th ed., Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of disease, Elsevier and Saunders, Outlander Anatomy archives (Image B), The Martian – the official trailer (HD) – 20th Century FOX (Image D), www.memecrunch.com (Image C), www.en.wikipedia (Image A)