Greetings faithful anatomy students! Today we continue our studies of the complex and elegant eye in Anatomy Lesson #30, The Eyes – Part 2. Anatomy Lesson #29 covered anatomy and function of eyelids, eyebrows and eyelashes. Today, we will discuss other structures that are designed to aid the eye in the vision it provides: bony orbit, orbital fat (yes indeed!), conjunctiva, lacrimal apparatus, and extraocular muscles.

And just to set the mood, eyes are extremely important in the English language. A quick glance (ha ha) yields more than 200 eye idioms: catch one’s eye, apple of one’s eye, in the blink of an eye, more than meets the eye, in a pig’s eye, all eyes and ears, a bird’s eye view, a sight for sore eyes, easy on the eyes, bedroom eyes (we know who has THOSE! ?), can’t take eyes off of, eye for an eye, catch one’s eye. Well, you get the idea…references to the eye makes English more colorful! Blink. Blink. Wink. Wink.

SPOILER ALERT: early in this lesson a wee spoiler appears from Diana’s eighth book of the Outlander series: no names, no dates, and no places. A warning will surface beforehand. Look for this (heehee…this is going to be fun!) obnoxious, glaring, flashing sign so you can skip and not whinge about something you would rather not read. Don’t say I didn’t warn ye!

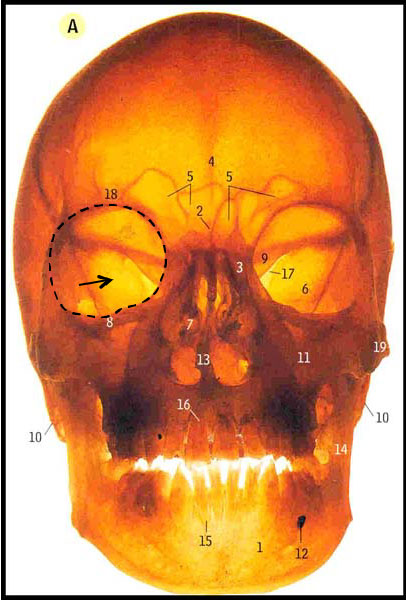

Let’s begin this lesson by considering the bony home for the eye. Each eyeball dwells in a cave known as the bony orbit (Photo A – dashed black line). Each orbit is composed of skull bones, some of which are so thin they readily transmit light (Photo A – black arrow). It isn’t even Halloween yet – Boo! ?

Photo A

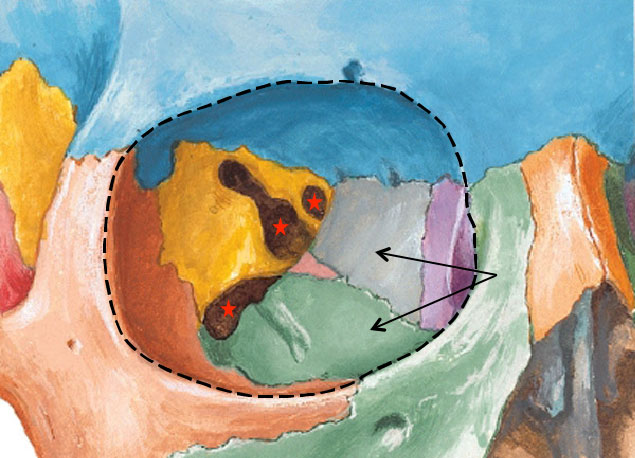

A whopping seven skull bones form each bony orbit. These are difficult to distinguish in the adult skull where the bones are fused, but easily discerned using a color coded image (Photo B – right bony orbit):

Blue = fontal bone

Orange = zygomatic bone

Green = maxillary bone

Violet = lacrimal bone

Grey = ethmoid bone

Pink = palatine bone

Gold = sphenoid bone

The bony orbits protect and support the eyeballs and provide attachment for several accessory structures. Although difficult to appreciate in a two-dimensional figure, each orbit is shaped like a cone: the apex (point) lies at the back and the base, or orbital rim, faces front (Photo B – dashed black line). Each apex has holes which serve as access ports for nerves and blood vessels to enter and leave the bony orbit (Photo B – red stars). The orbital rim, roof and temporal (side) walls are thick and strong but the nasal (medial) wall and part of the floor are thin and delicate (Photo B – black arrows). In fact, each medial wall is so thin it is known as the lamina papyracea (Latin meaning paper layer)!

Photo B

Indeed, a direct blow to the bony rim can break any of walls but the medial wall and floor are most commonly disrupted. Known as a “blowout” fracture, this injury appears in one of Diana’s prolific writings!

SORTA SPOILER ALERT: The following quote describes this type of injury. If you don’t want to read it skip the next two quotes and images and head straight for the furry mammal with the big eyes. NO! Not Rupert! It has orange eyes and Rupert doesn’t.

Herself correctly describes the consequences of a blowout fracture suffered by a character in her 8th book, Written in My Own Heart’s Blood, a.k.a. Moby. Claire relates:

A split lip and badly swollen eye seemed to be the chief injuries… The eye was swollen half shut …the underlying flesh a lurid palette of green, purple, and ghastly yellow. The eye itself was red as a flannel petticoat … I couldn’t move the globe of the eyeball upward at all…

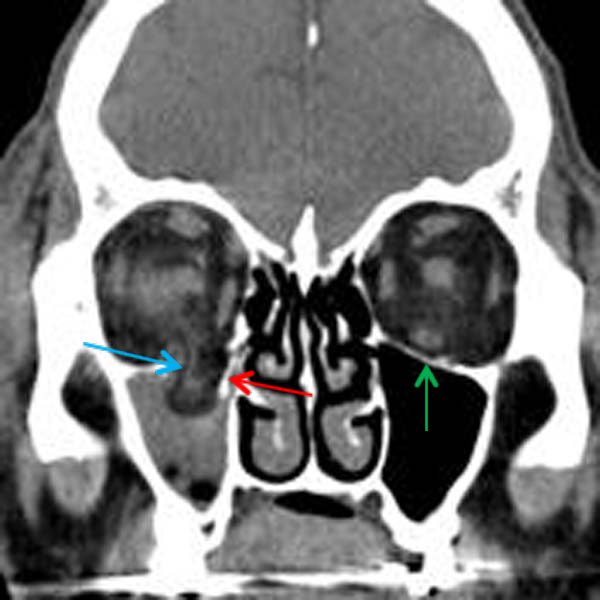

Clinical Correlation #1: Photo C shows the appearance of a right eye (on your left) with a classic blowout fracture juxtaposed with a normal left eye. The left eye has a white sclera, normal skin of eyelids and cheek and, when tested, the patient can elevate (lift) the normal eye. The right eye is patently abnormal: the sclera is red due to hemorrhage and the eyelids and cheek are bruised and swollen also due to hemorrhage. The right eyeball cannot be raised in tandem with the left eye; it is frozen with the gaze directed forward. Failure to elevate the right eye occurs because a small muscle of the eyeball (inferior rectus – see below) is trapped within the fracture, anchoring the globe and preventing its lift.

Photo C:

And, continuing the quote from Moby – again, Dr. Sassynach is our observer:

It was almost certainly what was called a “blowout” fracture, which had cracked the delicate bone of the orbital floor and forced a displaced bit of it—along with part of the inferior rectus muscle—down into the maxillary sinus. The edge of the muscle was caught in the crack, thus immobilizing the eyeball.”

YOU CAN LOOK NOW!

See, I told ye it wasna Rupert!

Photo D is a vertical CT scan through the skull. The paired ghoulish-looking white rings are the bony orbits. The patient’s left orbit (on your right) is normal; the black triangular space below it is the normal left maxillary sinus. These are separated by a thin white line, the orbital floor (Photo D – green arrow). The patient’s right eye shows a blowout fracture. The red arrow points to the white, broken and dangling bony bit of the orbital floor. The right maxillary sinus is grey because it is filled with displaced orbital tissues: the light grey material is prolapsed orbital fat (see below) and the aforementioned inferior rectus muscle (Photo D – blue arrow) which is trapped in the fracture anchoring the eyeball so it cannot be elevated. Very interesting stuff!

Photo D

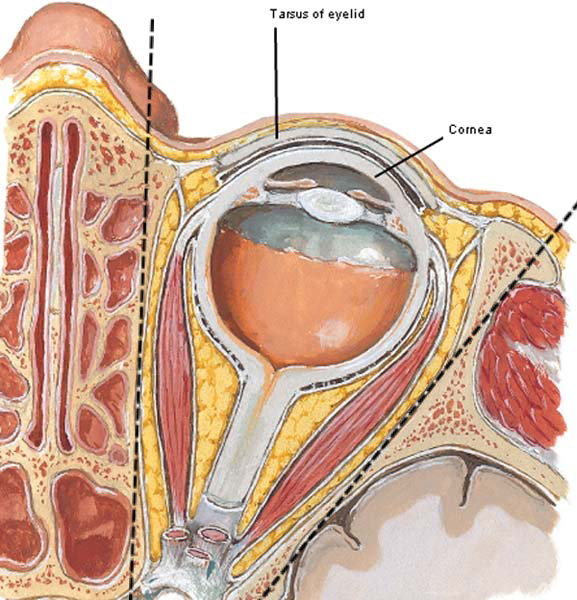

Now, structures other than eyeballs inhabit the bony orbits, including extraocular muscles, blood vessels, nerves and orbital fat. However, the eyeballs do not touch the bones of the orbit. Rather, they rest-in-a-nest of orbital fat that fills all the nooks and crannies not otherwise occupied. Orbital fat acts like a shock absorber cushioning the eyeball against trauma; it also serves as a socket in which each orb glides, slides and rotates. Photo E shows a horizontal section through the right eyeball and bony orbit; the cone shape of the bony orbit is easily appreciated from this birds-eye view (Photo E – black dashed lines). For orientation, the cornea and superior tarsus are labelled (Anatomy Lesson #29). See the yellow globs of “stuff” surrounding the eyeball? This is orbital fat and it is surprisingly abundant! Periorbital fat is also present but it lies superficial to the bony orbit being confined to eyelid margins and overlying orbital rim and cheek bone/zygomatic arch (Anatomy Lesson #8).

Try this: Close one eye and gently tap the soft tissues around the eyelids and overlying the orbital rim and zygomatic arch. Feel the springy and spongy nature of the soft tissues? This is periorbital fat. Orbital fat lies deep in the bony orbit and cannot be readily palpated.

Photo E

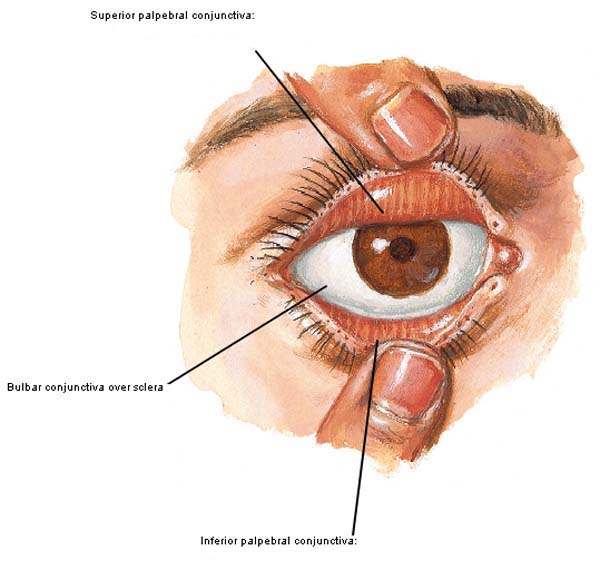

Most of the exposed eye is covered with the conjunctiva, a transparent, vascular mucous membrane. Bulbar conjunctiva overlies the sclera (white part) of the eyeball but it stops at the corneal rim and hence, does not cover the cornea. Palpebral conjunctiva lines upper and lower eyelids (Photo F).

Photo F

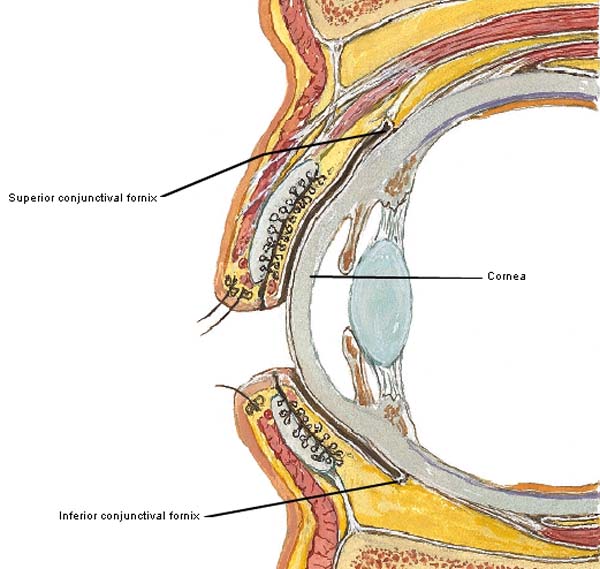

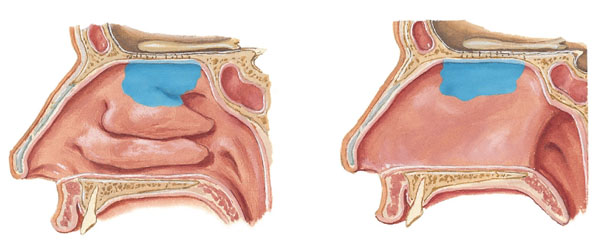

This design is possible because the conjunctiva reflects (turns) from the sclera onto the insides of upper and lower eyelids (Anatomy Lesson #29). This reflection creates a blind pocket or fornix where the sheet of conjunctiva turns from one surface onto another (Photo G – vertical section through eyeball and lids of eye). Thus, objects trapped on the exposed surface of the eyeball (e.g. contact lens) cannot move into the deep recesses of the bony orbit unless the conjunctival fornix is torn. The conjunctiva secretes mucus and contributes to the tear film (see below); it also produces immune cells that help protect the eyeball from microbes.

Photo G

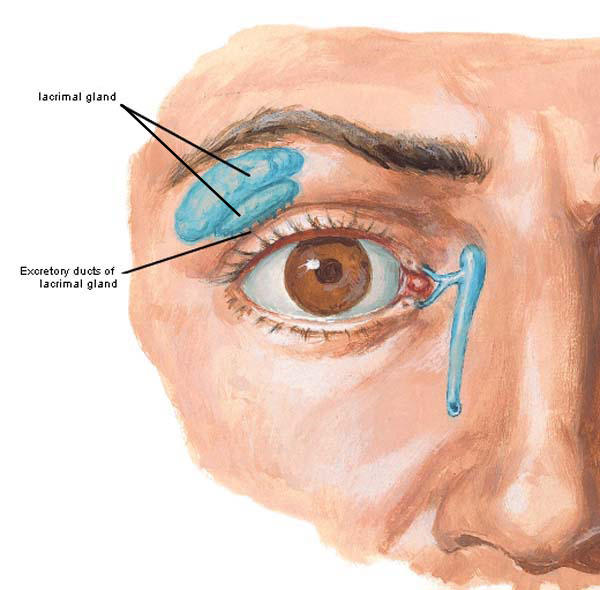

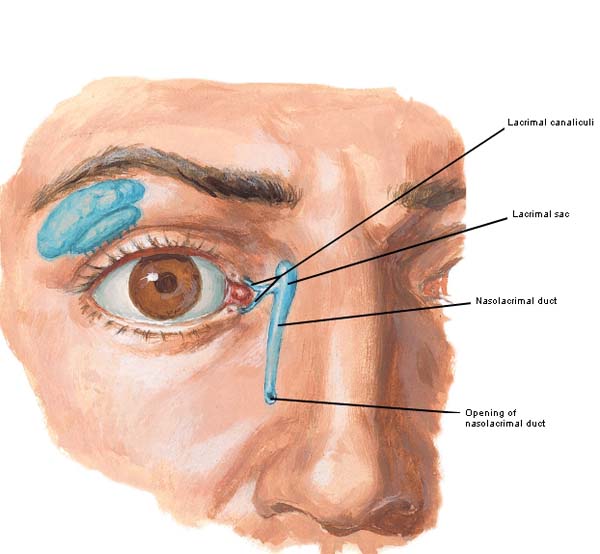

Now, it is time to consider the lacrimal apparatus (Latin meaning tears), an uppity name for the system which produces and drains tears. The lacrimal apparatus for each eye includes a lacrimal gland, lacrimal canaliculi, lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct.

The lacrimal gland is roughly the size and shape of a large almond. Most of it lies inside the bony orbit but a smallish part sits in the outer upper eyelid (Photo H). The purpose of the gland is to secrete (discharge) the aqueous part of the tear film. Several small ducts (tubes) pierce the conjunctiva and empty the secretion onto the surface of the eyeball.

Photo H

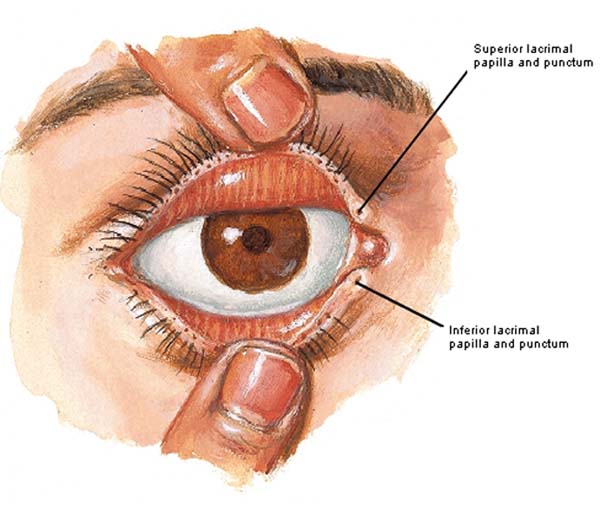

As the palpebral parts of orbicularis oculi (Anatomy Lesson #29) close the eyelids, the tear film sweeps across the exposed surface of the eyeball. To understand where it goes next, please see Photo I. Near the nasal ends of upper and lower eyelids, the eyelashes (Anatomy Lesson #29) disappear and small elevations appear on the lids; these are superior and inferior lacrimal papillae (pl.). Each papilla bears a small opening, the lacrimal punctum.

Try this: Face a mirror and gently pull down on the lower eyelid. See the small bump near the medial canthus (Anatomy Lesson #29)? This is the inferior lacrimal papilla. Find its tiny opening, the inferior lacrimal punctum. Repeat with the upper lid.

Photo I

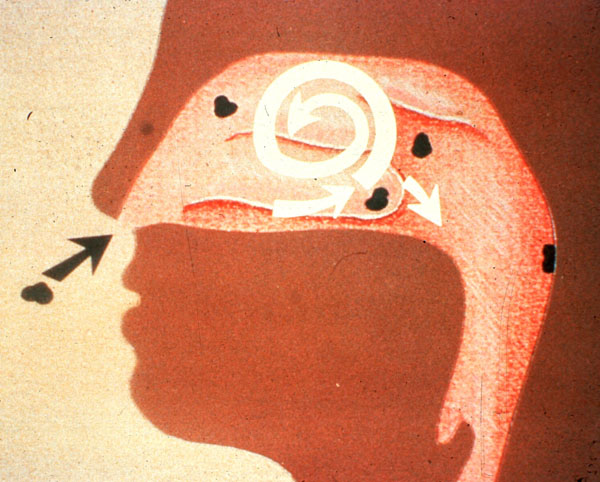

As the eyelids close, the tear film is swept toward the lacrimal puncta (pl.). Tears then enter the puncta and drain through the next group of lacrimal structures: lacrimal canaliculi (pl.), lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct. The paired lacrimal canaliculi are tiny ducts, each leading from its respective punctum to the lacrimal sac, an enlargement at the side of each nasal cavity. Tears then drain into the longer nasolacrimal duct.

Photo J

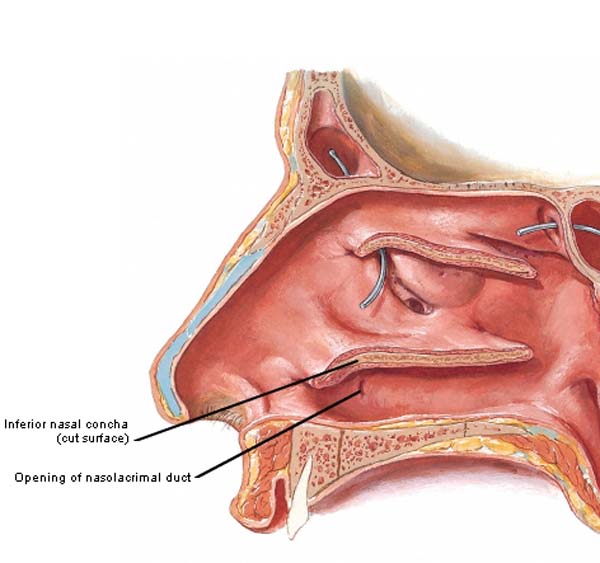

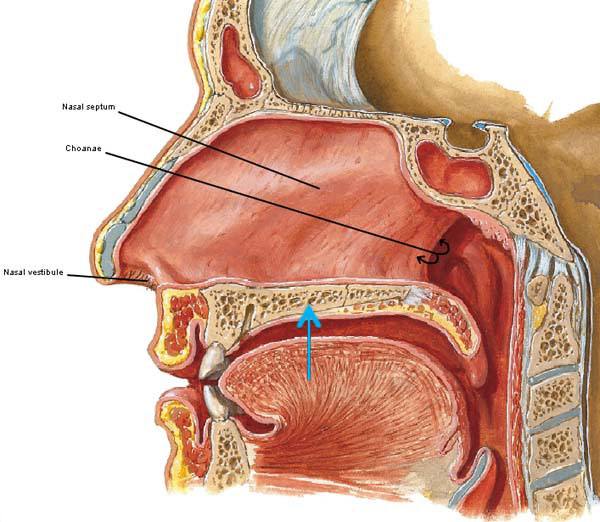

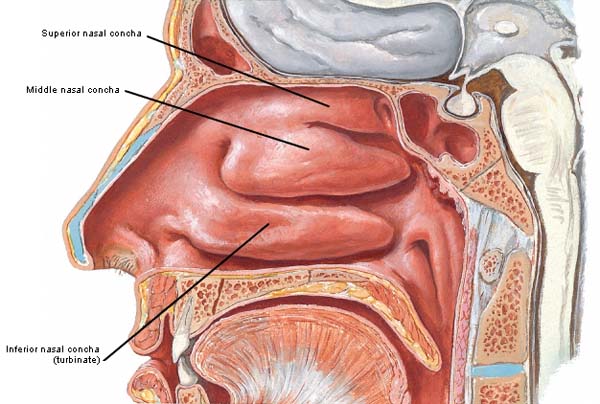

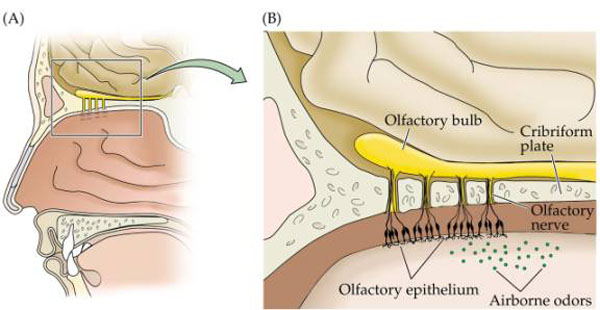

The nasolacrimal duct opens into the outer wall of each nasal cavity (Photo K – outer wall of right nasal cavity) under shelter of the inferior concha (Anatomy Lesson #28). After collecting in the nose, we blow out or swallow our tear film.

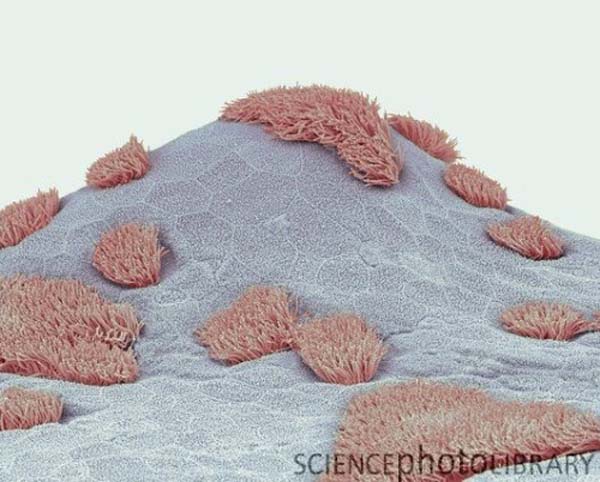

Hard to believe, but the thin tear film (40 µm or .0016 in) has three layers: 1) a deep mucous layer made by specialized conjunctival cells; 2) a middle aqueous film produced by the lacrimal glands; 3) an outermost lipid sheet released by tarsal glands (Anatomy Lesson #29).

Excessive tearing caused by pain or intense emotion, floods the lacrimal system, spills over the cheeks and fills the nasal cavity; this is why our nose “runs” when we weep.

Photo K

Can we see lacrimation (flow of tears) at work in Starz episodes? Oh, aye! Claire is a strong 20th century woman but I count at least six season one episodes where she weeps. This is my favorite: the lass is touchingly, tenderly tearful while confronting her beloved hubby about his intent to end it all (Starz episode 116, To Ransom a Man’s Soul). Intense emotions have her lacrimal system in full flush!

Speaking of crying, Jamie presents us with a gut-wrenching, Emmy-worthy (AHEM!) performance as a single tear overflows his lid and slips down his face. Bound by his word, he stays absolutely still as the wicked wolverine (oops, Wolverton) of Wentworth messes with his scars (Starz, episode 115, Wentworth Prison). Ugh! Puir lad!

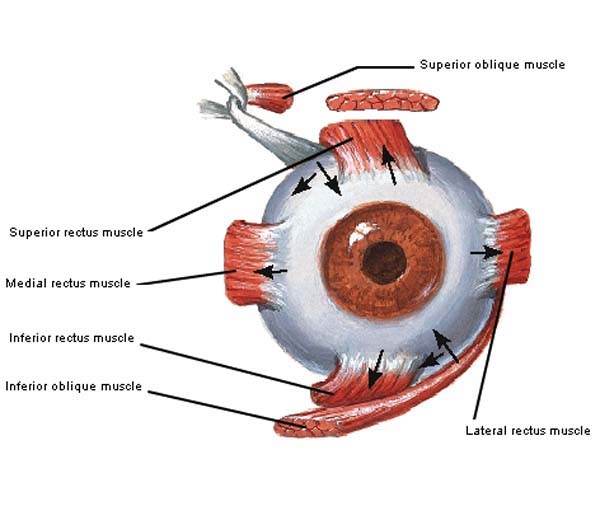

In addition to the above structures, each eyeball is moved by six extraocular muscles (intraocular muscles are inside the eyeball). These are all voluntary, strap-like muscles: four are recti (pl., Latin meaning straight) and two are oblique. The four recti muscles arise at the apex of the bony orbit, pass directly forward and attach to the eyeball like the hours on a clock face. In a left eyeball (Photo L – left eye) superior rectus inserts at the 12:00 position, inferior rectus at 6:00, lateral rectus at 3:00, and medial rectus at 9:00. Understand that the positions of medial and lateral recti are reversed in a right eyeball: medial rectus inserts at 3:00 and lateral rectus at 9:00. Superior oblique and inferior oblique are so named because they approach and insert into the eyeball at oblique angles.

Figure L

Movements of the head provide coarse adjustments to eye position but the extraocular muscles produce fine movements of the eyes. The four recti move each eye in linear directions: up (elevate), down (depress), toward the nose (adduct) and toward the ears (abduct). Oblique muscles roll each eye inward toward the nose (intorsion) or outward toward the ears (extorsion). The table below shows the main movements attributed to each of the six extraocular muscles. Each of these movements is aided by other extraocular muscles but these combos are beyond the scope of this lesson. Extraocular muscle movements are complex and require activation by three pairs of cranial nerves (from the brain) and several brain centers (too complex for our lesson).

| Superior rectus | Inferior rectus | Medial rectus | Lateral rectus | Superior oblique | Inferior oblique |

| elevates | depresses | adducts | abducts | intorsion | extorsion |

Each extraocular muscle has a yoke muscle that operates in concert to coordinate the gaze. For example, when we gaze to the right, the left medial rectus adducts the left eyeball and the right lateral rectus abducts the right eyeball. When we gaze to the left, the opposite muscle actions occur. Ditto for the obliques: as we roll our eyes to the right, the right inferior oblique contracts in tandem with the left superior oblique. The opposite muscles engage as our eyes roll to the left.

NOTE: both medial recti muscles adduct our eyes as we examine near objects but we will revisit this issue in the next eye lesson. Personally, I have never known a person who could simultaneously contract both lateral rectus muscles to abduct the eyes (eyeballs point toward the ears) although in an 1837 article from The London Medical Gazette, the author states that some men (?) can perform this maneuver. What about those lassies?

Speaking of maneuvers…get a keek of this! Och! All those lovely eye muscles working in tandem give us that gaze! Gah!

A simplistic description of the extraocular muscles at work can be seen at this link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4RxYRpIqLs!

Or, for an interactive and sophisticated version, try this link. It’s a bit involved but here’s how it works: go to the site http://www.bmc.med.utoronto.ca/anatomia/intro.swf, select orbit, then select structure & function, and lastly, select extraocular muscles. On the right is a giant H with a four-arrow circle. Capture the circle with your mouse and move it along the H to activate and view the six extraocular muscles at work. Very cool!

Hey, here’s a novel idea, let’s use more Starz episodes to help us understand eye movements! Time for Claire to hop onto the dissection table: here she contracts both superior recti to elevate her eyes (Starz, episode 103, The Way Out). She’s had, oh, um, roughly one hogshead of Colum’s finest rhenish wine – she canna really recall but enough to drop Angus under the table. Even Jamie is waaay impressed! Claire’s eyes also demonstrate an interesting Eye Rule #1: lift the eyes – lift the lids meaning levator palpebrae superioris (Anatomy Lesson #29) and superior recti muscles contract together.

Try this: close both eyelids. Now attempt to elevate the eyes while keeping the eyelids closed. You’ll find it is difficult to almost impossible because of Eye Rule #1: lift the eyes – lift the lids. If you can lift your eyes while keeping the lids closed, then per Rudyard Kipling (the (wo) is my addition):

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better (wo)man than I am, Gunga Din!

Claire is still in the dissection lab as both inferior rectus muscles contract to depress her eyes (Starz, episode 109, The Reckoning). Note that her upper eyelids are also lowered. She’s totally pissed at Jamie ‘cause his sword belt gave her a licking (Not the only lickin’ she gets. Snort)! Now, I could be wrong, but isna she wrapping her hair with an elastic band in prep for beddy bye sans Big Red One? Har har. Don’t think those bands were invented for another century or so. Eye Rule #2: lower the eyes – lower the lids; as the eyes depress (look down), the eyelids lower; inferior recti and palpebral part of orbicularis oculi contracting together. Yes! Bravo!

Try this: With eyelids widely open, try depressing your eyes. It is possible but verra difficult.

Ooooh! If looks could kill, Claire would be six feet under right here, right now! Casting the evil eye, wee wily LegHair (dissing the character not the awesome actress!) glares at Claire and Jamie as they share wine, words, gazes and body heat (Starz, episode 103, The Way Out)! Yoked together, her right lateral rectus abducts the right eye and her left medial rectus adducts the left eye. Her eyes are slightly elevated because her head is tilted to the right. Got it? Super-duper!

Now, LogHare isna the only character who can coordinate eye movements: fury and fear curdle Jamie’s wame as he watches Black-Jack-Rat run a dagger tip along Claire’s linea alba (Anatomy Lesson #16). He’s so friggin’ mad and scairt he can scarcely contain himself (Starz episode 109, The Reckoning). Yoked together, the right medial rectus adducts his right eye and the left lateral rectus abducts his left eye. Both eyes are also slightly elevated because his chin is tilted down. This keeps his gaze focused on the “object” of interest – rat man. Ye ken? Grand!

Let’s finish this lesson with some interesting tidbits about leeches (Hirudo medicinalis). Ahhh… What do leeches have to do with eyes? Well, hang on and let’s find out! Leeches have a long shared history with humankind. A mural from an 18th dynasty tomb in Thebes shows that leeches were used for medical purposes as early as 1300 B.C. Later, Latin and Greek writers Plautus, Cicero and Horace wrote of medicinal leeches using the names of bdella, sanguisuga or hirudo. The English word leech is from the Old English word “laece,” meaning doctor! Yikes! Today, many modern medical centers employ leeches in plastic surgery and trauma medicine especially to relieve venous congestion (Photo M). Mother Nature at her verra best!

Photo M

In the 18th century, medical practitioners transported leeches in special containers. Talk about fancy pet carriers! These beasties were not only placed on the skin but in some pretty hard to reach areas such as mouth, conjunctiva, rectum and vagina (Photo N – 18th & 19th century leech carriers). The clear tube at the bottom of this pic was used for placement in hard-to-reach places!

Photo N

And, when not being transported, leeches were kept in some verra purty jars. Nice housing, guys!

Photo O

Herself writes about leeches and healing in Outlander book. After Rupert beats Jamie in the great hall, Mrs. Fitz places leeches on his swollen face. Claire describes the event:

“That eye, now, lad, let’s have a look at that.”… “Still bleedin’ under the skin. Leeches will help, then.” She lifted the cover from the bowl, revealing several small dark sluglike objects, an inch or two long, covered with a disagreeable-looking liquid. Scooping out two of them, she pressed one to the flesh just under the brow bone and the other just below the eye… she explained to me, “once a bruise is set, like, leeches do ye no good. But where ye ha’ a swellin’ like this, as is still comin’ up, that means the blood is flowin’ under the skin, and leeches can pull it out… When ye use ’em on an old bruise, they just take healthy blood, and it does the bruise no good.”

The fabulous leech scene was filmed but edited from the aired version (Starz episode 102, Castle Leoch). So, here’s a wee bit of the deleted footage where Mrs. Fitz works leech magic (purported to be black licorice) on Jamie’s red and swollen left eye and cheek (see gif). Rupert’s eye punch broke blood vessels that hemorrhaged into extraorbital fat and loose connective tissue of eyelids, brow and cheek. Had the punch directly hit the bony orbit and eye, Jamie could have suffered a blowout fracture!

Claire de-claires (ha ha) that the leech-leach induces remarkable improvement, but she also uses this as a chance to cradle Jamie’s face. Yep! This lass just wants to pet that lad’s epidermis! Hang on, Claire – more skin touching is, erm, coming!

Eyes are endlessly amazing and today, we learned more about their accessory structures. Next lesson, we will study the eyeballs! For now, let’s end today’s fascinating topic with a quote about the oblique muscle action from funnyman Jim Carrey:

“Behind every great man is a woman rolling her eyes.”

A deeply grateful,

Outlander Anatomist

photo creds: Starz, www.sussexvt.k12.de.us (warning gif), Medicine: Perspectives in History and Art by R. E. Greenspan, 2006 (Photo O – 19th century leech jars), Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy, 4th ed. (Photos B – L), www.aapos.org (image of blowout fracture), www.collectmedicalantiques.com (Photo N – image of leech carriers), www.leeches-medicinalis.com/the-leeches/biology (Photo M – image of leech), www.radiopaedia.org (CT image of blowout fracture), http://funny-pics-fun.com (lemur)